The Curse of Hopelessness

The most mercilessly exact indicator of the depth to which corruption has eaten away at the Ukrainian state is not statistics, not opinion polls – it is the sheer irritation felt by a typical citizen when he or she comes across an article about the harm of corruption.

This irritation is one’s typical reaction to the feeling of helplessness, to the situation when it seems that there is no chance to change anything. All rationale of the dangers of corruption has been explained to the society, understood and accepted by it. What is worse, it has become mundane. Moreover, the citizens sincerely believe the corrupt authorities to be one of the country’s biggest problems, make clear statements about strengthening of anti-corruption activity, demand convictions of corrupt officials.

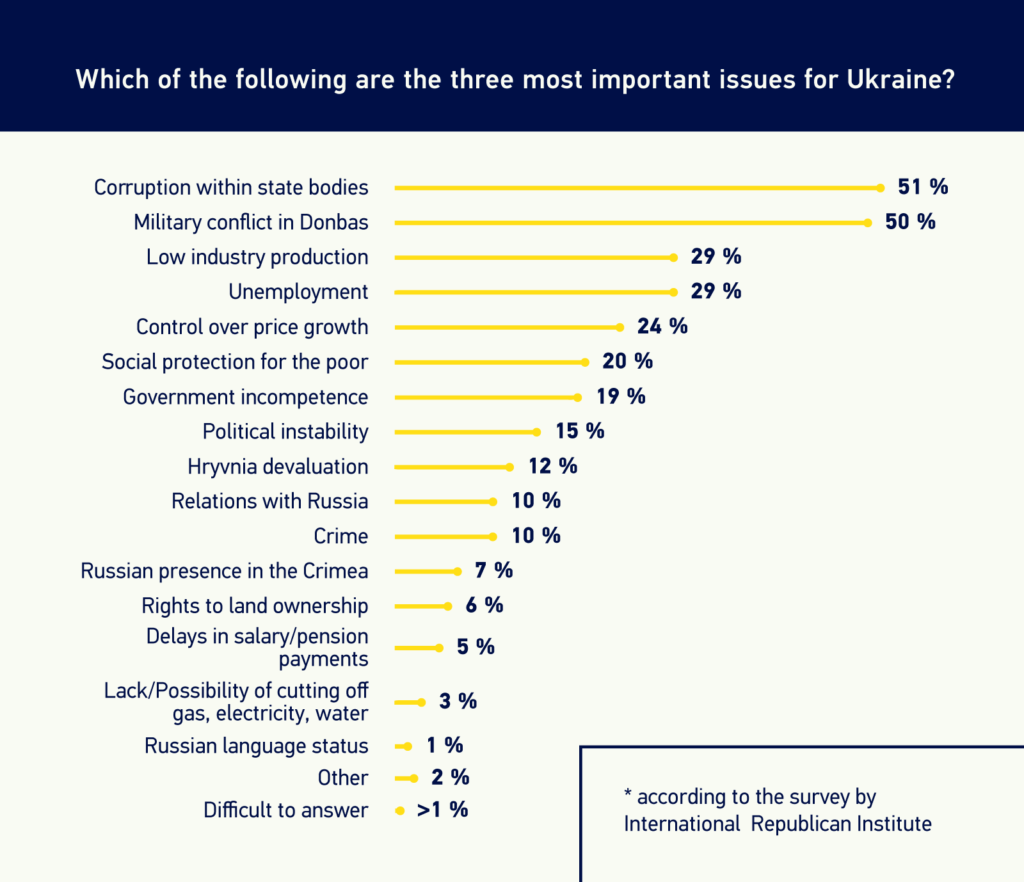

According to the opinion poll of Ukrainian citizens carried out by the American International Republican Institute in the summer of 2017, Ukrainians believe corruption to be the country’s gravest problem – 51% of the respondents mention it among other problems. Almost the same number, 50%, have brought up the war in the Donbas area. The next problems, following far behind, are related to economy – low industrial production and high unemployment rate have been mentioned by 29% of the respondents.

The fact that these requirements fall on deaf ears does not cause irritation, it makes one want to protest. Irritation, on the other hand, comes exactly from the feeling of helplessness. A person feels that nothing depends on them, that the scope of the problem is so great that its solution is too big a challenge to tackle not only for this one person but for the entire country. Which, in its turn, means that the public groups campaigning against corruption engage in idle chatter which has nothing to do with real life. Why keep talking about fighting corruption if in practice it looks invincible?

Mission Possible

However, practical experience proves that it’s quite possible to tame corruption. It does not work everywhere, and it’s never easy, but there are enough success stories across the world.

The most illustrative example of a country’s anti-corruption transformation is Singapore and its legendary Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. Neither politicians’ greed, nor mafia’s cruelty, not even the skepticism of most people was able to stop what, as the legend goes, one single person managed to see through. Lee Kuan Yew announced that the main principle was the rule of law and he proved numerous times that for him, this principle outweighed personal connections. Today, many countries study and try to implement Singapore’s anti-corruption practices – including China, which learned from experience that not even death penalty can teach corrupt officials to see the difference between public funds and their personal budget.

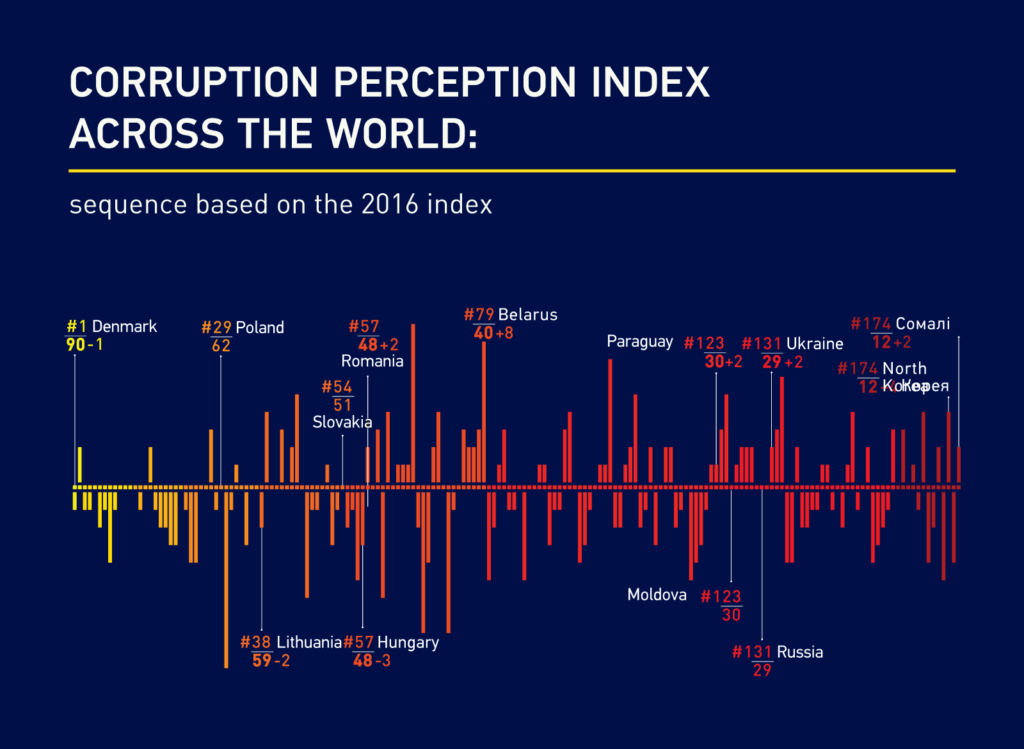

In the reputable rating Doing Business, Singapore is now the runner-up – not only because of a level of corruption phenomenally low for an Asian country, but also thanks to abolition of previously existing multiple concords, licenses and other authorizations (which, actually, largely contribute to the abundance of corruption). The leader of the rating is New Zealand, a liberal country which does not aspire to the status of a world or even regional leader, while the powerful authoritarian China is on the 78th place – two lines above Ukraine with its still-unreformed judiciary and painstakingly sabotaged “anti-corruption” policy which render the country’s claims to be called democratic exhaustingly inappropriate.

Actually, any successful democracy is a case study of society’s victory over corruption. Now, it is hard to imagine how strong the corruption was in the government of the USA during Prohibition, when criminal syndicates bought influence in legislative hearings of certain states and in Washington in bulk and what inventive methods the FBI and specialized groups of Department of the Treasury had to use to break the links between the mafia and the Government.

Balance Disrupted

Of course, the current situation with corruption did not come into being today, but it is today that the authorities have the ultimate responsibility to resolve this problem – at least because it was their main promise following the Revolution of Dignity, the fundamental basis of the social contract concluded back then between the electorate and the political elites. While it is undeniable that over the past three and a half years they have taken many steps in the right direction, it is hardly unnoticeable that these steps are yet to yield a practically tangible result. The establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office was not complemented with adequate transformation of the judiciary – as the result, there are court decisions on just a fourth of corruption-related cases (according to information of the NABU, on 24 out of 92 cases referred to the court; actual proceedings on 30 cases have not even started yet). The establishment of the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption and launch of the register of property declarations have not yet produced an effective system of identification and prosecution of violations yet either (a functioning system of automatic analysis of declarations is not ready, still). The establishment of the State Investigation Bureau, which is supposed to undertake the investigative functions of the current Prosecutor General’s Office, is suspended without any adequate explanation whatsoever.

And yet, fighting against corruption is still proclaimed the top priority by the President and leaders of political groups. Then again, this comes as no surprise and is hardly new.

“In any case, I will not let corrupt officials control the politics. I will burn this phenomenon with red-hot iron.”

It was not Petro Poroshenko who said this in one of his recent speeches, it was Viktor Yanukovych back in 2010.

We already know the worth of the former president’s words, and we’ll find out the worth of the same statements of the incumbent one (for instance, about “cutting off the hands” of MoD corrupt officials) soon enough, ahead of the forthcoming elections.

How Citizens “Underfinance” the State

The relations between citizens and the state are traditionally based on mutual reproaches that the collected taxes are not enough. Interestingly, this is often used as a reason for delaying the reforms. However, careful analysis can challenge this reasoning.

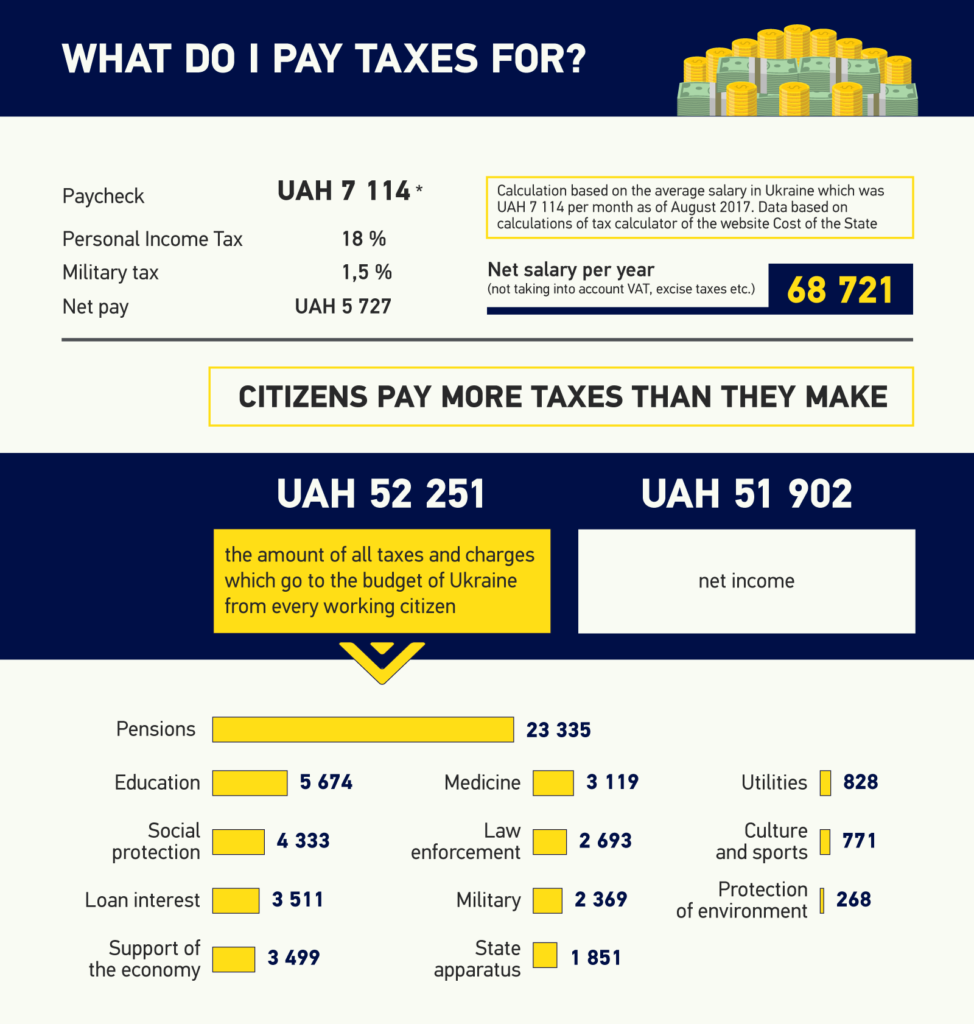

In 2013, the website Cost of the State (http://costua.com) published an analytical article by Dmytro Boyarchuk, who illustrated what taxes and for what services the citizens pay to the state.

“For instance,” writes the author, “in 2011, every worker paid UAH 2.5 thousand (which constituted 1.5 monthly paychecks at that point) for “free” education. At first sight, this number astounds, but if you take into account that the average monthly paycheck in education was UAH 2,000 per month, this contribution of a taxpayer sort of amounted to the right to an individual monthly course from the Ministry of Education.”

Of course, most taxpayers did not receive any services from the state as a refund for this payment. The situation seems to be similar in other categories of taxes. For instance, the author supposes that while over 58% of all accounted for state reimbursements to the population goes through the category “support of retired people,” people who actually need state support barely receive a third of these funds.

Remember that this money cannot ever be called “the state’s money” (here we can recall Margaret Thatcher’s famous saying that “There is no such thing as public money; there is only taxpayers’ money.”) And if the budget is organized in a way which makes it impossible for tax payers to receive adequate compensation in state services for the taxes they pay, it technically means that the people pay the state for nothing. Often they actually end up having to pay a “contribution” in the form of a bribe to receive one of services guaranteed by the state.

This situation is very unlikely in democratic countries at least because they have a smooth-running mechanism of a taxpayer’s control over how the state spends his or her money. In Ukraine, like in many former USSR republics, such public control mechanisms do not exist, which makes public funds an easy target for corrupt officials. Figuratively speaking, all the taxes paid to the state can be considered stolen from the moment of their payment.

While it’s debatable which part of the budget chaos is caused by violations and which by managerial incompetence (neither would really surprise anyone at this point), there is no major difference for a taxpayer (and customer of state services) anyway.

The same website, Cost of the State, offers a calculator which allows to calculate the sum of taxes charged per taxpayer based on the sum of his/her monthly wage according to the Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of February 18, 2016, by categories. According to this calculator, citizens pay more money in taxes than they make. Taking into account the aforementioned as well as the uncertain situation with the tax service (according to the 2017 budget approved by the Verkhovna Rada, is terminated from January 1, but the tax police has not been created in its place), it is probably not very surprising. Without public control, any state gets out of hand and starts showing gibberish in its reports instead of actual meaningful numbers – after all, nobody will read those reports except people who know how to explain said gibberish if they have to.

Personal Interest

The defeat of corruption in the US was possible not only because that’s what the American electorate categorically demanded, not only because of the effective judiciary functioning in the country, but also because people had a clear understanding that corruption would get into the pocket of every single one of them. They realized it and they refused to take it for granted. Because they were aware that the country was theirs, knew why and for what they paid taxes, did not consider it self-explanatory that the state government or Washington had the right to fiddle with that money – the citizens’ money.

For most citizens of today’s Ukraine this approach is still strange. By the Soviet (and imperial) tradition, they subconsciously see the government as owners of the country, and feel something like its employees. For a person stuck in the post-soviet mindset, democracy is largely a mere formality, the possibility to effectively control the government feel like unnecessary luxury, taxes are viewed mainly as payment for the right to receive the guaranteed minimum goods, and the mundane bribe becomes the most natural way to obtain something that exceeds this minimum. Tolerance to corruption thus gradually transforms into participation in it.

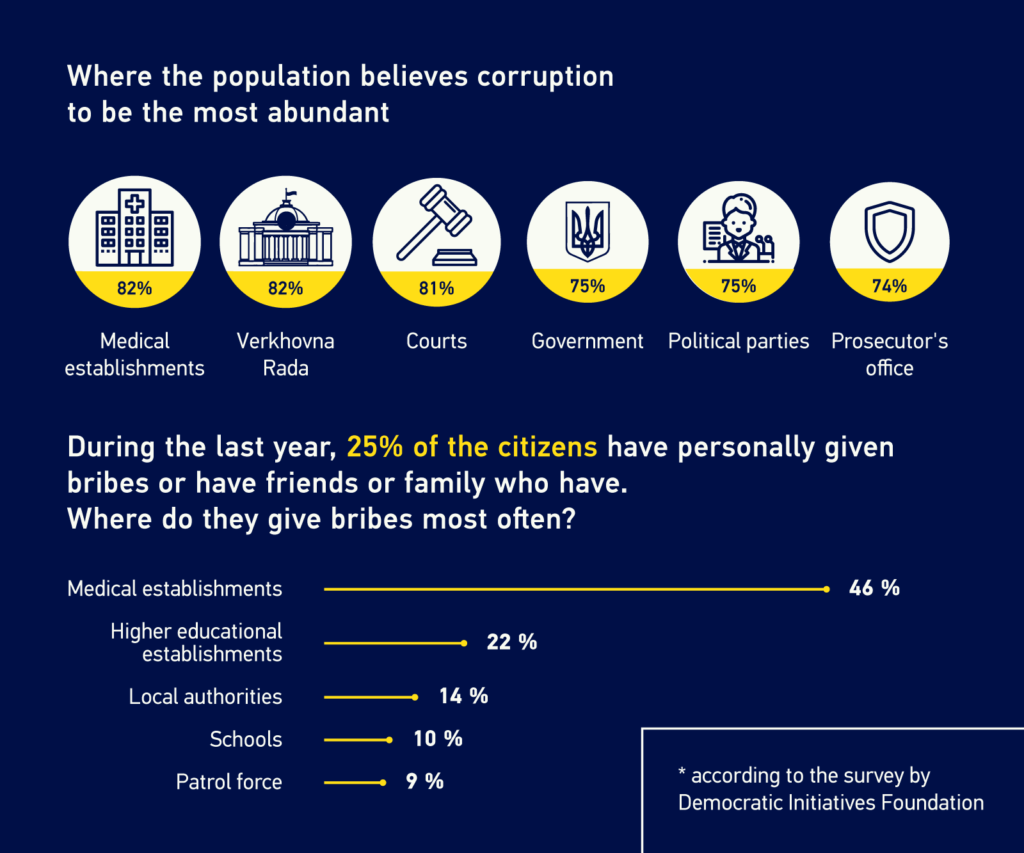

The recent survey by Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation has shown that a quarter (25%) of the surveyed Ukrainians have given bribes themselves or have friends or family who have done it. The most frequently mentioned type was bribes in medical establishments, followed by universities, schools, local authorities and the police. The abundance of corruption in the country is assessed by people as extremely high: 90% of the surveyed are confident in this assessment, and only 2% believe the problem to be blown out of proportion. The most corrupt agencies identified in the survey were courts, Verkhovna Rada, Prosecutor’s Office, the government, the customs office and medical establishments.

These sentiments, namely such “division of property” between the authorities and the electorate, lead to the conditions where the Ukrainian state, while maintaining a democratic façade, remains an authoritative oligarchic regime.

The Revolution of Dignity gave the country a hope that this archaic regime would be dismantled for the sake of building a more modern society. But in order for that to happen, the attitude of the citizens to the state has to change dramatically – in mass conscience, it has to transform from the “owner” and “benefactor” into a tool for resolution of acute problems of the citizens, become not only a useful service in high demand, but also citizens’ literal property.

Nobody steals from himself and nobody encourages theft of their property. Corruption flourishes only where property is alienated from the citizens this or that way. But as long as Thatcher’s famous saying remains an exotic idea in Ukraine as opposed to a principle applied in everyday practice, a bribe to a doctor or scheming with budget financing will not be considered an unacceptable absurdity in this country.

Such a transformation of the public opinion obviously cannot happen overnight, in any case, it will be the result of long joint effort of the citizens, public establishments and governmental institutions. And while the state is traditionally lagging behind in this area (which is typical not only of Ukraine – almost any country, however democratic it may be, state administration strives towards conservatism, not dynamic modernization), the citizens have an excellent opportunity to be proactive and start with turning personal aversion to corruption into the practical principle “I don’t bribe.”

An adult person aware of their citizenship doesn’t need any other appeals and recommendations – personal aversion to theft and understanding that every refusal to bribe damages corruption as a phenomenon are usually enough. If the society is as concerned with the scope corruption as surveys say, there have to be more such refusals happening.

This will also help reduce the irritation from “futility” of talks about the harm of corruption: participation in the social anti-corruption movement, even on such a personal level, will move the subject from talk to action. In its turn, it will increase public requirements to the authorities, which so far manage to combine lack of will and lack of competence in fighting corruption and seem to find no good reason to review this approach.

.

Serhii Berezhnyi with TI Ukraine