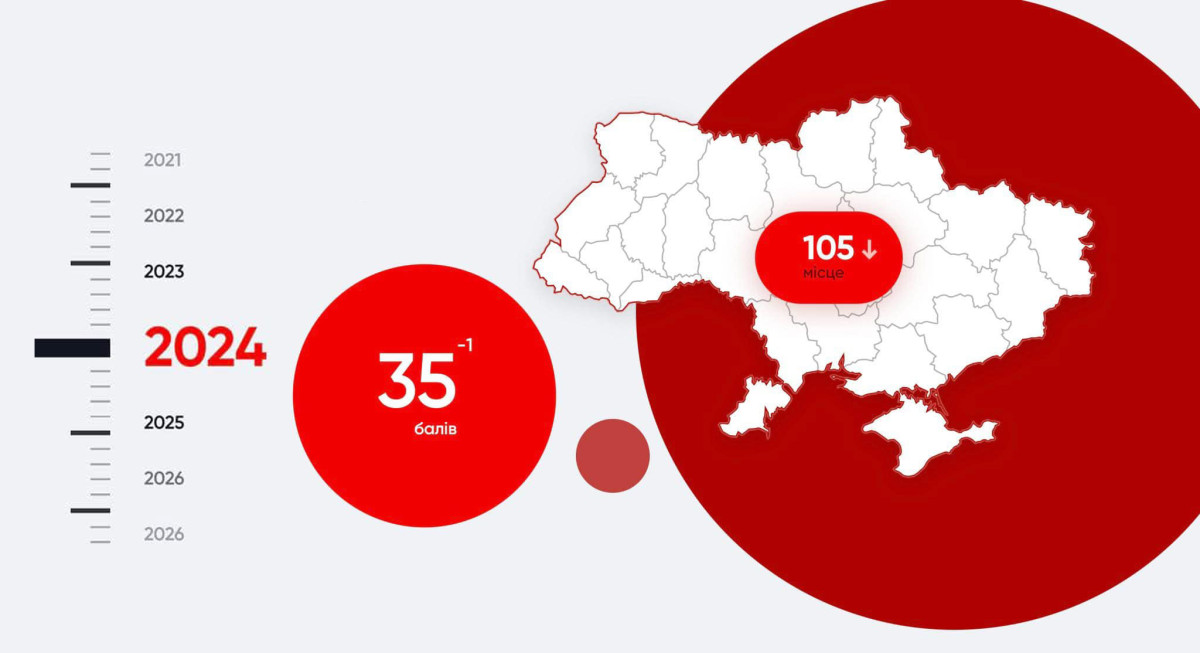

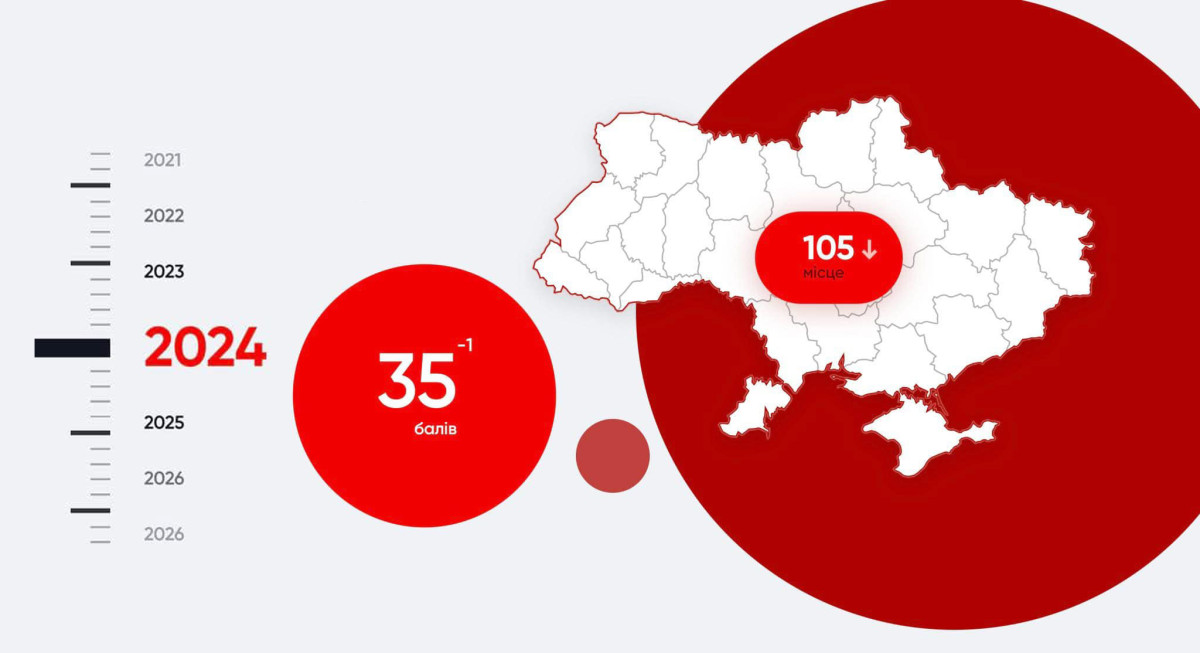

Ukraine scored 35 out of 100 points on the 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). In a recent study by Transparency International, Ukraine ranks 105th out of 180 countries.

Thus, after a significant increase of three points in 2023, Ukraine lost some of its position in the anti-corruption fight in 2024. The main drivers of change continue to be reforms aimed at European integration and the fulfillment of international obligations.

However, the current results suggest that many reforms are being implemented only formally, or that their implementation is being deliberately stalled. Therefore, the drop in points in 2024 indicates that merely focusing on the programmatic implementation of Ukraine’s commitments is insufficient, and that the execution of the reforms is not as high-quality as intended.

Serbia also scored 35 points according to the current study. The Dominican Republic is one point ahead of Ukraine in the index, while Algeria, Brazil, Malawi, Nepal, Niger, Thailand, and Turkey scored fewer points.

Like Ukraine, most EU candidate countries exhibit trends of stagnation in the fight against corruption. For example, the indicators for Georgia (53 points, 53rd place), Montenegro (46 points, 65th place), and Turkey (34 points, 107th place) remained unchanged during the year. Serbia’s performance decreased by 1 point (35 points, 105th place), while North Macedonia (40 points, 88th place) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (33 points, 114th) each lost 2 points. Only two countries improved their performance. Moldova’s position increased by 1 point to 43 points (76th place), and Albania’s improved by 5 points to 42 points (80th place). Thus, only Moldova and Albania have shown progress this year, with Albania registering the strongest dynamic among all EU candidate countries.

The current results suggest that many reforms are being implemented only formally, or that their implementation is being deliberately stalled.

Among its neighbors, Ukraine remains ahead of Russia—the terrorist state lost 4 points in 2024 and fell to 154th place with 22 points. Similarly, Belarus, Ukraine’s northern neighbor, also lost 4 points last year and now ranks 114th with 33 points.

Among its western neighbors, only Moldova improved its overall position, scoring 43 points and ranking 76th. For the second consecutive year, Romania maintained a score of 46 points, ranking 65th. All other countries worsened their positions: Poland (53 points, 53rd place) and Hungary (41 points, 82nd place) each lost 1 point, and Slovakia lost 5 points (49 points, 59th place). Thus, Ukraine and most of its neighbors—except Moldova and Romania—worsened their performance on the Corruption Perceptions Index in 2024.

Ukraine and most of its neighbors—except Moldova and Romania—worsened their performance on the Corruption Perceptions Index in 2024.

What components make up Ukraine’s CPI-2024 indicator?

As in the previous year, Ukraine’s CPI-2024 results were calculated based on eight studies covering the period from February 2021 through September 2024 inclusive. Events that occurred in the fall of 2024 were most likely not included in the latest index.

In three of these studies, Ukraine’s performance improved: the Bertelsmann Transformation Index for 2024 increased our score by 2 points, while both the Freedom House report and the Global Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index improved our score by 1 point each. In the remaining five studies, Ukraine’s scores decreased. The Economist’s Country Risk Rating and the Varieties of Democracy Project reduced our results by 2 points, Global Insight’s Country Risk Rating and the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey reduced our score by 3 points, and PRS Group’s International Risk Survey for 2024 resulted in a 6-point decrease.

Taking the above data into account, one can argue that the overall change in Ukraine’s CPI indicator is primarily due to systemic trends rather than isolated point factors.

At the same time, in 2024, the global movement Transparency International clarified the overall methodology for studying the Corruption Perceptions Index for all countries. As a result, some scores in specific studies have changed partially—not primarily due to shifts in the actual perception of corruption among the countries covered, but because of technical adjustments in converting the indicators to an updated 100-point scale.

The Bertelsmann Foundation Transformation Index for 2024—which recorded a 2-point increase for Ukraine—was conducted from February 2021 to January 2023 and included the opinions of 280 experts from around the world. In particular, they evaluated the extent to which officials who abuse power are prosecuted or punished. Since this study is conducted biannually, Ukraine’s improvement in its score is largely attributed to the general adjustment of the Transparency International methodology.

At the same time, the 1-point increase in Ukraine’s Freedom House report was due less to methodological changes and more to an actual update in the assessment of Ukraine’s progress. This report examines public perceptions of corruption; the business interests of senior politicians; financial disclosure laws and conflicts of interest; as well as the effectiveness of anti-corruption initiatives, among other factors.

According to the Freedom House report, improvements in Ukraine’s corruption perception were influenced by several factors: the resumption of public e-declarations, the initiation of a case against former Supreme Court chairman Vsevolod Kniazev, the exposure and legal evaluation of abuses in defense procurement, and the postponement of launching the Register of Oligarchs following recommendations from the Venice Commission. At the same time, the study identifies threats to the effective implementation of the SAP—stemming from sabotage by certain corrupt government agencies—as negative trends.

Instead, the Rule of Law Index from the Global Justice Project—which examines the extent to which government officials exploit their positions for personal gain—indicates minor positive trends. According to more than two dozen experts who contribute to this index for each country, Ukraine experienced a slight improvement in all measured indicators between February and June 2024.

Taking the above data into account, one can argue that the overall change in Ukraine's CPI indicator is primarily due to systemic trends rather than isolated point factors.

What further anti-corruption measures should Ukraine implement to improve its CPI performance?

Most of the positive changes in Ukraine’s corruption perception over the past two years resulted from the authorities’ efforts to implement European integration recommendations and secure financial assistance from international partners. In contrast, the negative events were largely generated internally and primarily highlighted the shortcomings in the functioning of state bodies. Moreover, for methodological reasons, many of these negative events have not yet been included in CPI-2024, but they will be incorporated into next year’s study.

In other words, Ukraine’s performance in the Corruption Perceptions Index indicates that our progress so far has largely been driven by international obligations. The implementation of these recommendations served as the primary incentive for the Ukrainian authorities to work efficiently on enhancing the country’s capabilities.

In general, we can identify three key documents that define the trajectory for Ukraine’s future development:

- Ukraine Facility Plan;

- European Commission’s EU Enlargement Report;

- the IMF Extended Fund Facility (EFF).

According to these documents, in 2025 Ukraine should take comprehensive steps to strengthen its ability to combat corruption:

- increase the number of judges and staff at the High Anti-Corruption Court;

- continue efforts to remove obstacles to investigations of high-profile corruption cases, including the seizure and confiscation of assets derived from crime;

- properly implement the SAP;

- streamline internal NACP procedures;

- strengthen the NABU’s capacity to conduct forensic examinations and perform independent wiretapping;

- finalize an external performance audit of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine involving three independent experts with international experience, and publish the corresponding report;

- introduce legislative amendments that enable the SAPO to handle requests for extradition and mutual legal assistance, and to address the consequences arising from the end of the pre-trial investigation period (referred to as “Lozovyi’s amendments”);

- adopt the law on the comprehensive reform of the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA);

- delineate the powers between the Accounting Chamber and the State Audit Service;

- continue harmonization of Ukrainian legislation on public procurement.

Also, do not forget the list of priority reforms required to receive aid, which was provided earlier by the previous U.S. President’s administration. Similarly, one of our key priorities will be to implement the concrete steps outlined in the Rule of Law Roadmap. This document is still being developed by the Ministry of Justice and must later be approved by the EU Council.

Collectively, these requirements represent a coordinated program aimed at achieving comprehensive, high-quality European integration for Ukraine, while also enhancing its economic viability and investment attractiveness. Therefore, implementing these recommendations will not only enhance Ukraine’s anti-corruption efforts but also contribute to its broader development and global engagement.

CPI study: how it works

Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is a ranking calculated by the global organization Transparency International since 1995. The organization does not conduct its own surveys. The Index is calculated based on 13 studies of reputable international institutions and think tanks.

The key indicator of the Index is the score, not the rank. The minimum score (0 points) means that corruption actually replaces the government, while the maximum (100 points) indicates that corruption is almost absent in society. The index assesses corruption only in the public sector.

CPI incorporates the perspectives of business representatives, investors, market researchers, and others, reflecting the private sector’s view of corruption in the public sector.

It is important to keep in mind that CPI measures perception of corruption, not the actual level of corruption. A higher score for one country compared to another does not necessarily mean that the former has less actual corruption—it simply indicates that it is perceived as less corrupt.

The CPI methodology has been approved by the European Commission for its robust statistical approach.

CPI assesses experts’ perceptions of public sector corruption by examining factors such as bribery, embezzlement of public funds, nepotism in public service, state capture, the government’s ability to implement integrity mechanisms, the effective prosecution of corrupt officials, excessive bureaucracy, and the adequacy of laws on financial disclosure, conflict of interest prevention, and access to information, as well as the protection of whistleblowers, journalists, and investigators.

Why do we need a CPI?

– The CPI covers more countries than any single source.

– The CPI compensates for the error in different sources using the average of the results of at least three different sources.

– The CPI scale of 0 to 100 is more accurate than other sources, as some have a scale of 1 to 5 or 1 to 7, which results in many countries receiving the same results.

– The CPI balances different perspectives on corruption in the public sector and has a neutral approach to different political regimes.