Last April, a government project was launched to restore a number of settlements that had been destroyed as a result of the war. Its uniqueness was in the application of a new, integrated approach to reconstruction—with the planning and complete transformation of these settlements—so the project was designated as experimental.

The settlements were planned to be rebuilt within two years, and the Agency for Restoration was selected as responsible for the implementation of the experiment. But the results of the first year can hardly be considered successful—out of more than three hundred planned objects, only one has been restored so far. We were not given a clear answer, but most likely, it is the repair of the road in the Kherson region.

The government and regional authorities blamed the Agency for Restoration and its head for the failed project, given the low performance. The latter, in turn, mentioned the long delays on the part of the government and the lack of funding. In the end, the political upheavals that accompanied the project were one of the reasons for the dismissal of the head of the Agency.

We decided to find out what went wrong and studied the conditions of the experiment and the stage at which the restoration of selected settlements is now. As it turned out, the unsuccessful launch of the project was due to both the lack of proper legal regulation and obstacles on the part of its participants and the government.

Gaps in the experiment conditions

The first stage in the project implementation was the selection of settlements for comprehensive restoration. The government-approved list includes:

- Borodianka and Moshchun villages in the Kyiv region;

- Trostianets city in the Sumy region;

- Posad-Pokrovske village, located on the border of the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions;

- Tsyrkuny village in the Kharkiv region;

- Yahidne village, Chernihiv region.

All for different reasons. Yahidne and Tsyrkuny were included in the list on the initiative of the regional military administrations, while Trostianets was included on the initiative of the Office of the President. Probably, for the same reason, Moshchun and Posad-Pokrovske were included in the list—the president visited them shortly before the start of the experiment.

The level of destruction should have been the determining criterion for selection, but it differed significantly among the settlements. More than 70% of all buildings were destroyed in Moshchun, while in Borodianka and Tsyrkuny, this figure only reached 15%, and in Trostianets—only 4%.

This demonstrates the lack of a unified approach to selection because in some cases, preference was given to settlements with a significantly lower level of destruction, and an order from above contributed to the inclusion of some in the list. Given that the number of destroyed settlements in Ukraine is growing and probably not all will be rebuilt, it is impossible to do without the development of criteria and procedure for determining those settlements that will be subject to comprehensive restoration.

The next stage after the approval of the list of settlements was the selection of objects for restoration, which lasted more than three months.

The lists of objects were formed according to a complex scheme. Local self-government bodies (LSGBs) submitted their proposals to the regional military administrations (RMAs). They were processed and submitted to the Agency for Restoration for approval. Some RMAs repeatedly submitted updated lists, and some lists were returned for revision. That is, RMAs had to contact the local authorities for clarification. All this took extra time.

The selection procedure was also negatively affected by the lack of requirements and criteria for restoration objects. The Kyiv RMA submitted a list of objects, which included 108 private residential buildings, for approval by the Agency for Restoration. But, according to the head of the Agency, the prime minister did not see the point in the reconstruction of housing within the experiment because this could be done through the compensation program. For Moshchun, no such project was ever approved. In Posad-Pokrovske and Yahidne, more than a hundred private residential buildings were approved for restoration.

The absence of legislatively established criteria for the selection of objects to be restored and the mediation of the RMA slowed down this process and shifted the actual launch of the project to autumn 2023. In addition, the lack of a unified approach to the selection of restoration projects led to the fact that the reconstruction of Moshchun was almost completely excluded from the experiment.

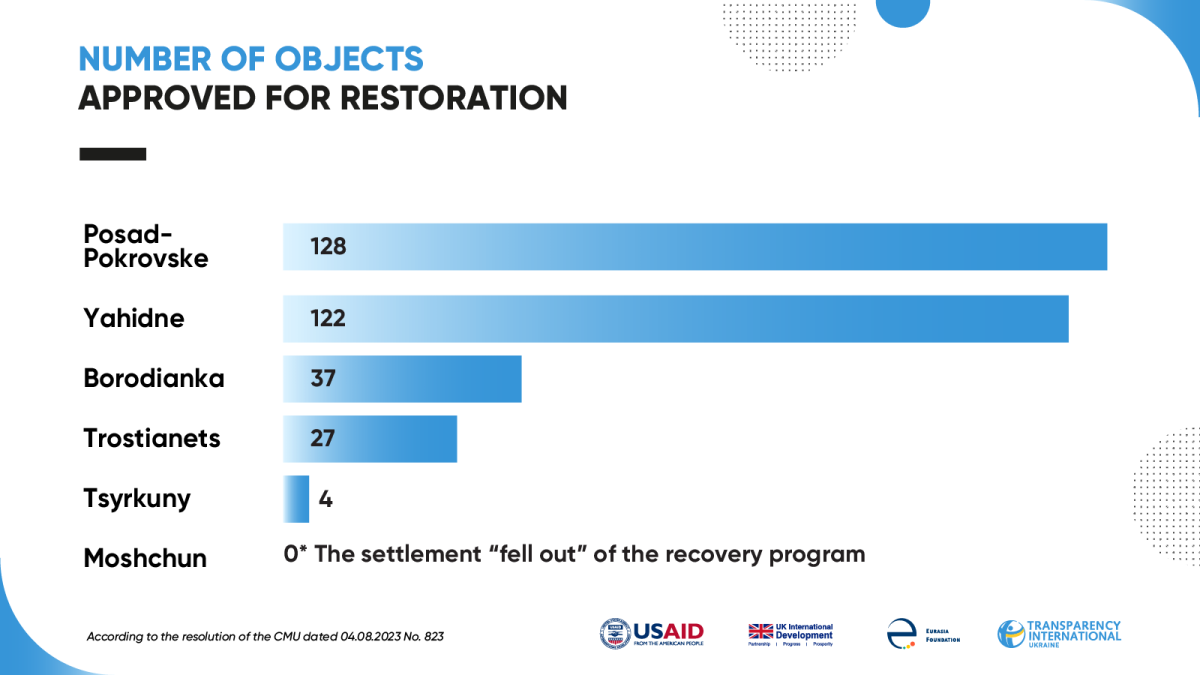

In the end, the approved list included 306 objects for restoration. However, the screening of part of the objects by RMAs and the Agency resulted in a disparity in their number depending on the settlement. Thus, in Posad-Pokrovske and Yahidne, the approved list included 128 and 122 objects, respectively, while in Tsyrkuny, the number of objects amounted to only 4.

All because the Kharkiv RMA prioritized the restoration of the social and administrative infrastructure of the village. Can the reconstruction of four infrastructure objects be considered a comprehensive restoration of the settlement? Hardly. In this case, it would be reasonable to replace the settlement. This idea was even voiced by the head of the Kharkiv RMA; however, this was due to constant shelling of the village. But the matter of replacing Tsyrkuny did not go beyond a discussion at the level of the regional administration.

Funding delays

The lengthy process of selecting projects for restoration directly affected the financing of the experiment because the funds for its implementation in 2023 were allocated simultaneously with the approval of the list of these projects—on August 4.

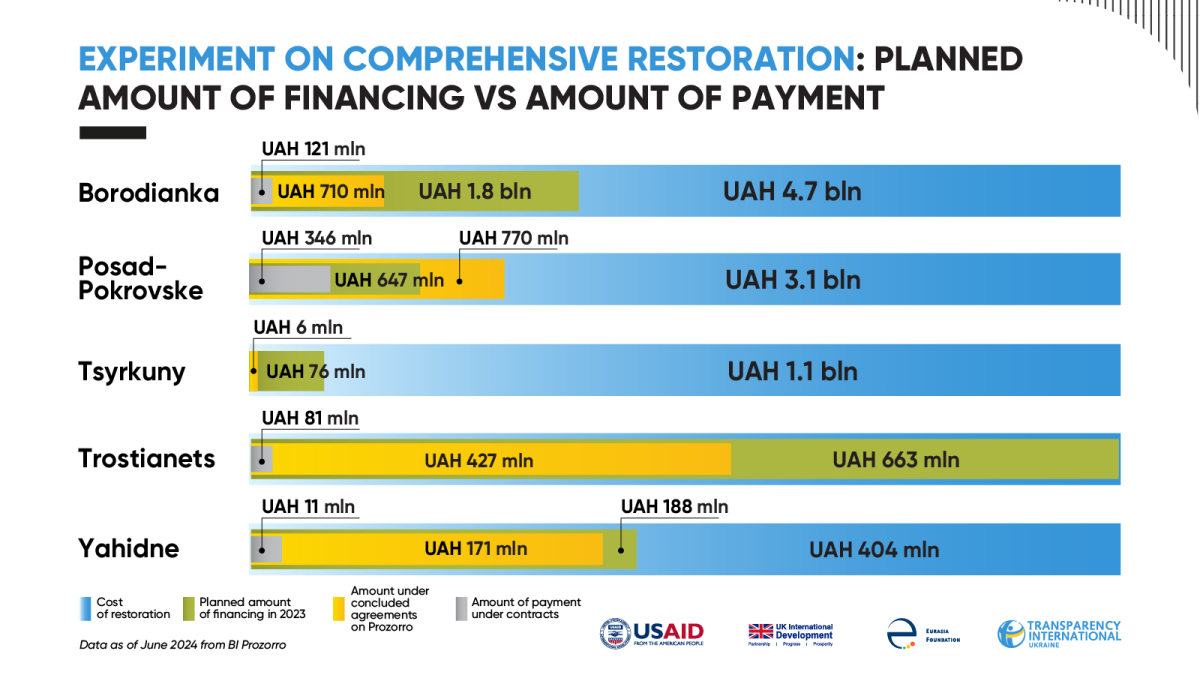

Trostianets was the only settlement in which restoration projects were planned to be fully funded in 2023. Instead, only 7% of the expected cost of the projects was allocated for the restoration of Tsyrkuny last year. The costliest was the restoration of Borodianka (UAH 4.7 billion), and the least funds were planned for Yahidne (UAH 404 million).

However, the regional restoration services were able to start procurement only in mid-September, after the approval of the budget program passport. As a result, by the end of 2023, the costs of the experimental project for comprehensive restoration—advance payments and payment under the service acceptance certificates—amounted to only UAH 559 million out of the planned UAH 3 billion.

Three months before the end of the budget year, the restoration services conducted at least 237 procurement transactions for the development of project and estimate documentation, construction, and technical supervision. The level of approximate savings (the difference between the expected cost and the amount under the concluded contract) for procurement averaged 21%.

In 2023, the amount under contracts reached slightly more than 11% under the contracts concluded. Therefore, with the end of the fiscal year, there was a need for additional funding to pay for what was done in 2024. In March, the government reallocated the rest of the resources from the Remediation Fund for 2023 but did not agree on the allocation of funds for comprehensive recovery. Therefore, due to the lack of funding, contractors of most projects suspended works, and in some cases, they even terminated contracts.

Government procedures and political instability

According to the latest report of the Agency for Restoration, the institution sent a request for the allocation of the remaining unused funds in the amount of UAH 2.8 billion to continue the reconstruction works in February 234.

As of June, the draft order on financing was under consideration in the Cabinet Secretariat. It had not been considered for more than a month because the relevant government committee on reconstruction, headed by the former Vice Prime Minister for Reconstruction of Ukraine, did not hold meetings. However, the dismissal of Kubrakov should not have caused a collapse in the work of the committee because according to the existing distribution of powers, he should have been replaced by another deputy prime minister—Fedorov. However, the sensitivity of the issue of budget allocation for the experimental project is likely to hold back the approval of the relevant decision until the appointment of the next Minister for Communities, Territories and Infrastructure Development.

But while there has been no appointment, time is lost; it could have been used to restore the social infrastructure and housing of those who, because of participation in the experiment, refused compensation or other reconstruction mechanisms. Therefore, the government should reconsider its position on the effective suspension of project financing or offer an alternative that would meet the interests of its participants.

This publication was prepared as part of the Digital Transformation Activity, funded by USAID and UK Dev.