You have probably seen the news about the High Anti-Corruption Court confiscating millions of hryvnias’ worth of property from dishonest officials without a verdict. Look at the well-known 2021 case on the confiscation of UAH 1.2 million from the already deceased Illia Kyva, the sum he received from the lease of a “pulp pit” belonging to someone else.

Similar confiscations continue to this day. In late August, the HACC recovered an apartment worth almost UAH 2 million from the head of one of the recruitment centers in the Vinnytsia region. A similar thing happened to the head of one of the SBI departments; UAH 7 million was recovered.

Such confiscations have been used in Ukraine since 2019, when parliamentarians significantly improved the new mechanism for combating corruption—civil forfeiture of unjustified assets.

This year alone, the HACC received 10 claims from SAPO prosecutors requesting to confiscate assets worth tens of millions of hryvnias; this is the value of the property that officials allegedly tried to hide from the eyes of law enforcement officers.

So, what is this magical forfeiture? Let’s figure it out.

Such confiscations have been used in Ukraine since 2019, when parliamentarians significantly improved the new mechanism for combating corruption—civil forfeiture of unjustified assets.

Andrii Tkachuk

What is civil forfeiture?

Recognition of assets as unjustified and their recovery into the national income or, simply put, civil forfeiture, is a legal tool by which the court forcibly seizes property from dishonest officials, whose purchase they could not have financed.

For example, the case of Hryhorii Riabykin, the Kryvyi Rih District Council member. In 2021, together with his wife, he bought an elite Mercedes-Benz S 450 car for UAH 3.6 million, but at the time of purchase, they had a total of savings and income reaching only UAH 1.7 million. Riabykin did not manage to explain the origin of an additional UAH 1.9 million; so, the court found these funds unjustified and confiscated them into the national income.

Civil forfeiture does not require proving the guilt of a person in committing a crime or other offense. The only important thing is the fact of obtaining an asset, the legality of which cannot be confirmed.

Interestingly, the confiscation of unjustified assets is not a punishment; it is merely a way to strip officials of the property that they received illegally and whose origin they tried to hide from law enforcement officers.

A vivid example is the case of Andrii Anosov, the former head of the Department of Preventive Activities of the National Police, who in 2021 was involved in the scheme to issue weapon permits for bribes. The participants of the scheme made at least UAH 4 to 8 million on it, and UAH 2.3 million and USD 35,400 of unknown origin were subsequently found on his accounts, which the HACC recognized as unjustified and returned to the state. The defendant might have skillfully concealed the connection of these funds with bribes, which he allegedly took for issuing permits. In this case, the HACC is not obliged to assess such facts.

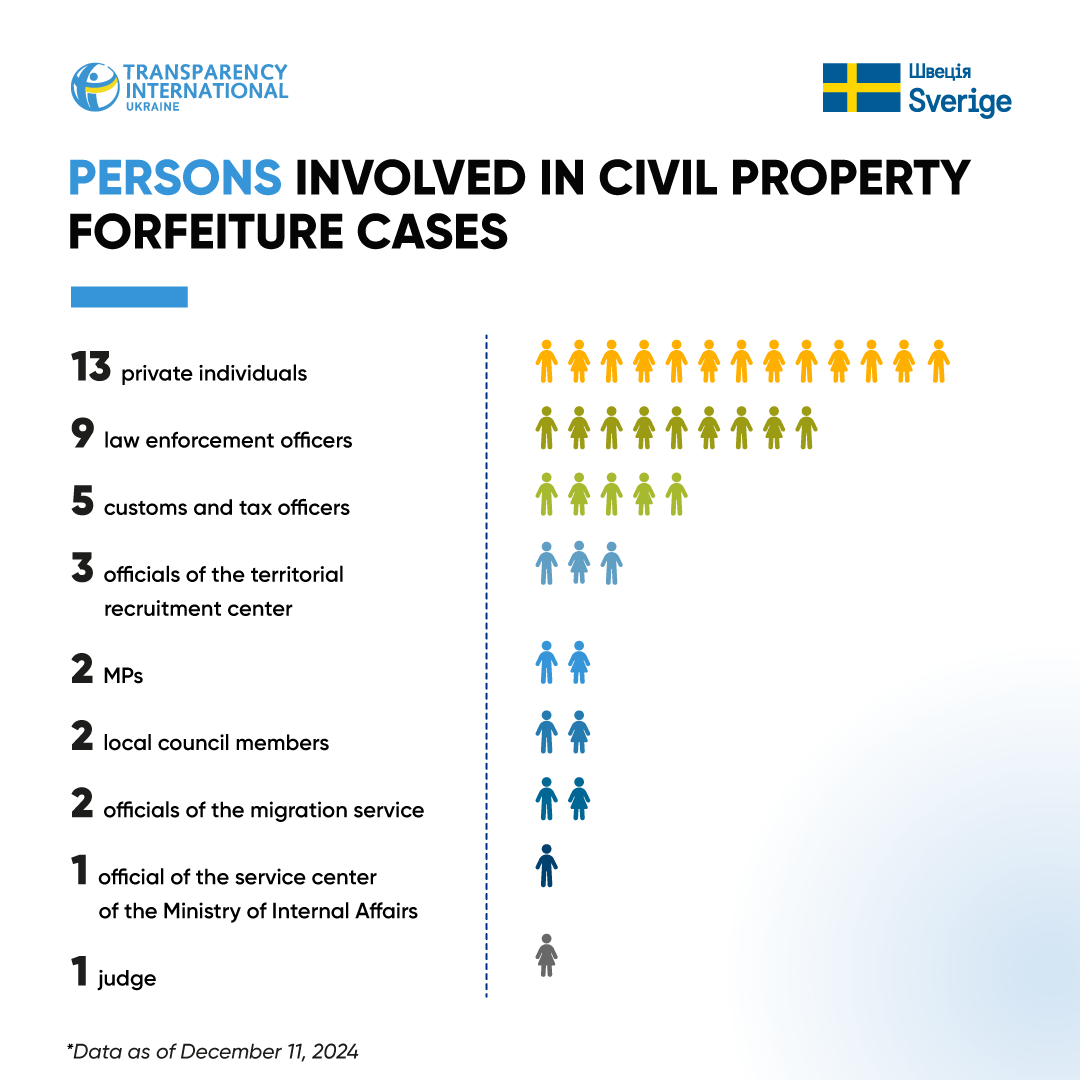

There can be hundreds or even thousands of such cases—just look at how many defendants there are. Therefore, the task of the state was to regain control over the assets that officials had received with a high degree of probability by abusing their powers.

In 5 years after the introduction, civil forfeiture has really proved to be an effective and universal tool because it takes 7 times less time to recover such property into the national income than to convict a person for an offense.

Civil forfeiture does not require proving the guilt of a person in committing a crime or other offense. The only important thing is the fact of obtaining an asset, the legality of which cannot be confirmed.

Andrii Tkachuk

How is the confiscation of the unjustified property of the official carried out?

To confiscate property of dubious origin, it will suffice to prove that the official could not have purchased it for themselves or through other persons using the legitimate income. To achieve this, the NABU and the SAPO collect evidence, mainly public declarations, data from the tax service, banks, state registers, service centers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, etc.

The NACP helps them to identify such facts because quite often, employees of the National Agency find inconsistencies during the declaration check or the monitoring of their lifestyle. This happened in September to spouses Denys Tsvietkov and Iryna Lemesheva, officials of the National Police. The NACP found their unjustified apartment for UAH 2.4 million. The evidence, together with the claim against the spouses, has already been referred for consideration to the High Anti-Corruption Court, which is the only one in Ukraine hearing such cases and confiscating unjustified assets.

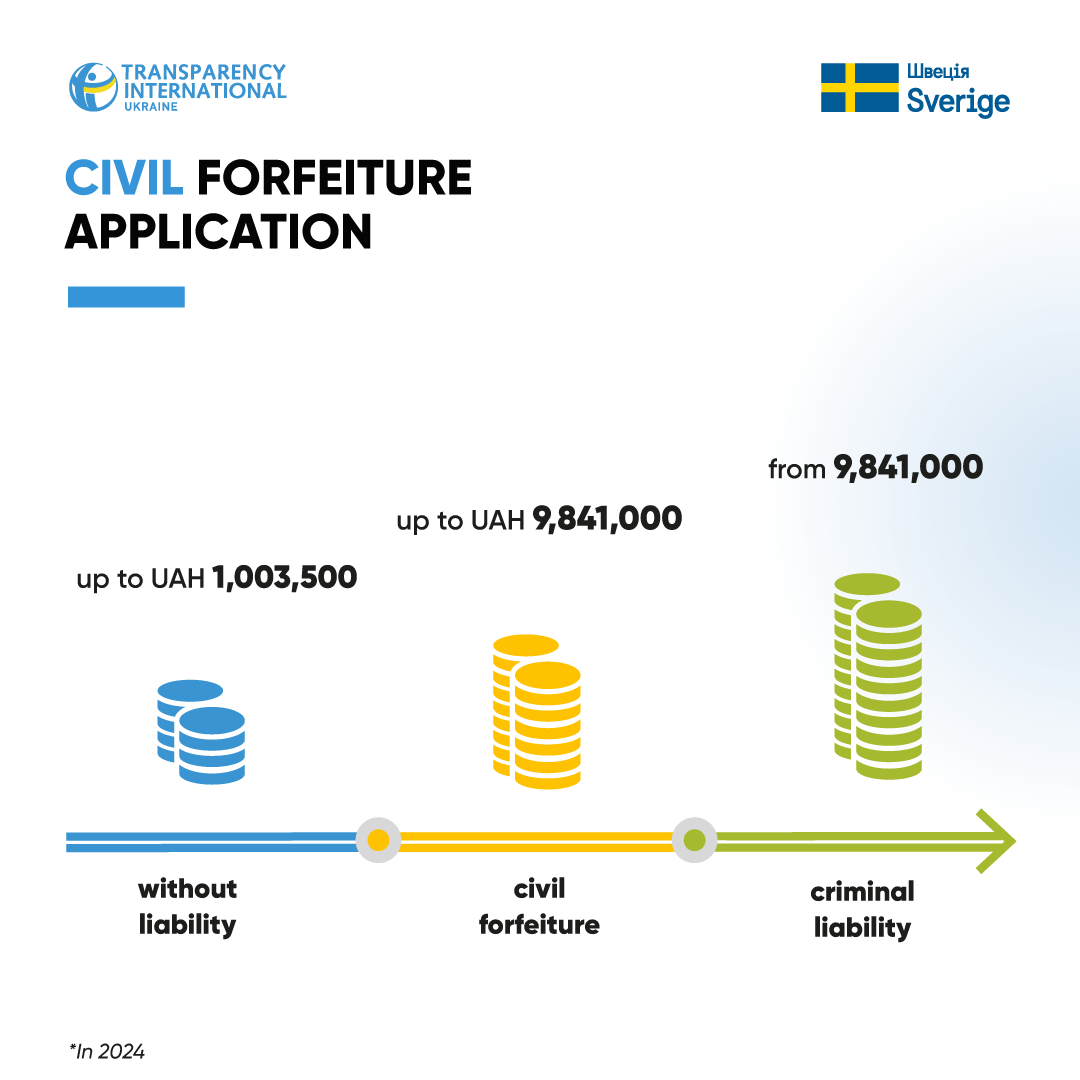

For civil forfeiture to be applied, not only the very existence of property of dubious origin belonging to representatives of the state or local self-government is important, but also its value: it should be within the range from UAH 1,003,500 to UAH 9,841,000 (in 2024).

The upper limit is linked to criminal liability for unlawful enrichment (Articles 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine), which awaits an official when they come to own assets worth a fairly large amount—more than UAH 9,841,000. This limit changes every year. The lower limit is related to the effectiveness of this tool. After all, the overall costs of the state spent on the organization of the civil forfeiture process—the collection of evidence by the prosecutor and proving the unjustified nature of the asset in court—will not correspond to the effectiveness.

For civil forfeiture to be applied, not only the very existence of property of dubious origin belonging to representatives of the state or local self-government is important, but also its value: it should be within the range from UAH 1,003,500 to UAH 9,841,000 (in 2024).

Andrii Tkachuk

Civil forfeiture in figures

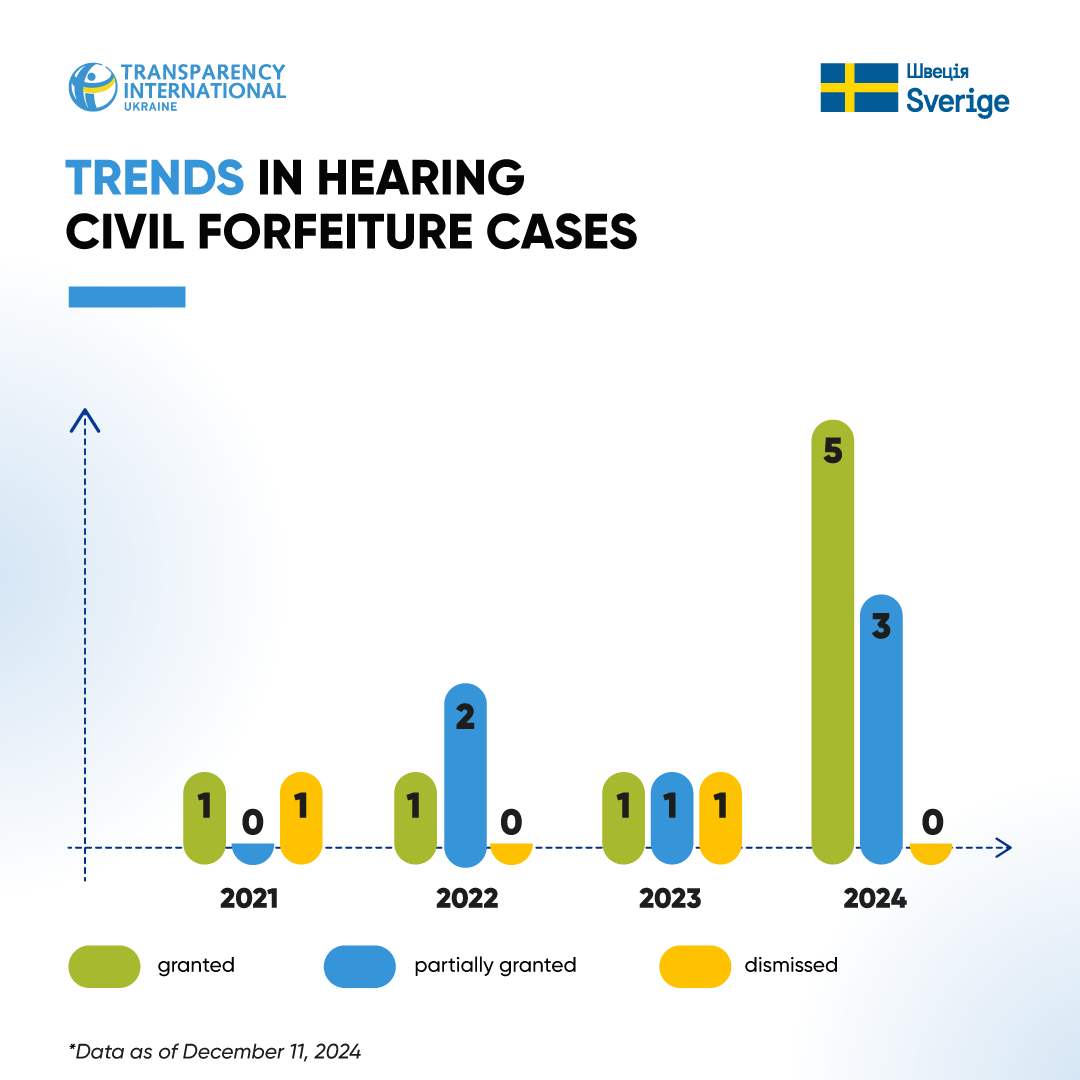

As of December, the HACC issued 16 rulings in such cases. The court applied civil forfeiture 14 times and refused to do so twice. 6 cases are still pending in the first instance of the HACC, and 2 cases are being heard by the appellate instance.

The most striking indicator of the effectiveness of this tool was the volume of confiscated assets. In more than three years of its application, UAH 51 million was recovered into the national income. In addition, the cases that are currently being heard might bring about UAH 26.7 million more in the event of a favorable outcome.

This year, after the declaration was resumed, we witness a noticeable increase in the number of claims from the SAPO; as of December 11, prosecutors filed 10 claims. Some of them feature record-high amounts, such as UAH 8.7 million belonging to Taras Polienko, deputy head of the Main Directorate of the National Police of Kyiv, or UAH 7 million belonging to Oleksandr Savchenko, head of a territorial service center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the Dnipropetrovsk region. Some of these claims have already been considered and granted by the HACC.

The most striking indicator of the effectiveness of this tool was the volume of confiscated assets. In more than three years of its application, UAH 51 million was recovered into the national income. In addition, the cases that are currently being heard might bring about UAH 26.7 million more in the event of a favorable outcome.

Andrii Tkachuk

What challenges still need to be overcome?

The figures we have mentioned are only a starting point for the real possibilities of civil forfeiture because many obstacles stood in the way of its more active use. The first one is the declaration suspension due to Russia’s full-scale military aggression.

Although the issue with the declaration suspension has been resolved, there are still those that need to be addressed. Recently, we at Transparency International Ukraine devoted a whole study to the problems of civil forfeiture and found that the process, albeit successful, is not so smooth.

For example, the inconsistency of case-law in such cases allows the defendants to make money on their unjustified assets. All because the judges have not yet found a single approach: what exactly should be confiscated—the property or its value.

A significant part of the HACC decisions obliged officials to pay the value of the property at the time of its acquisition to the treasury. However, this approach did not consider the fact that, for example, over time, the price of real estate increases, and money can be made on these fluctuations.

The similar thing happened in the case of Anna Bisiuk, the head of a Lviv customs department, whose apartment was recognized as an unjustified asset. Then, instead of confiscating the property, UAH 1.86 million spent on its purchase was decided to be confiscated. However, in 3 years after the purchase of the apartment until the decision on confiscation, she might have made UAH 3 million due to rising real estate prices (especially in the western part of Ukraine).

To rectify this, the HACC must confiscate either the asset or its actual value and not recover the value of the property at the time of its acquisition.

In addition, quite often, the defendants own such property indirectly through nominal owners, relatives, or friends, which complicates the consideration of the case. These people do not file declarations, and the possibility of the court to check the financial capacity of such persons to buy the property of dubious origin is not mentioned anywhere in the legislation. Therefore, MPs must allow the court to check the property status of persons associated with the official.

Neither does Ukrainian legislation describe exactly how the collection of evidence in such cases shall take place. The law entrusts the solution of this issue to a greater extent to prosecutors and the court, but this is not enough. The uncertainty of the collection rules remains, and this may lead to the receipt of evidence that the court will not be able to consider due to its inadmissibility.

Therefore, the Anti-Corruption Court shall develop uniform criteria and approaches for collecting evidence. This would allow prosecutors to obtain a better evidence base and have a better chance of obtaining a fair decision.

Therefore, the Anti-Corruption Court shall develop uniform criteria and approaches for collecting evidence. This would allow prosecutors to obtain a better evidence base and have a better chance of obtaining a fair decision.

Andrii Tkachuk

***

Civil forfeiture is a fairly new tool, and it has a considerable potential that the state should use to fight corruption and more. These are not just loud statements: such prospects are mentioned in the Asset Recovery Strategy. In April 2024, the EU adopted Directive 2024/1260, stating that civil forfeiture shall also apply to assets acquired by criminal organizations if they cannot be recovered through criminal proceedings.

But before that, it is crucial to consider and rectify the problems that have arisen in the application of civil forfeiture. A small but rich sample of decisions of the High Anti-Corruption Court on the recognition of assets as unjustified shows that this mechanism needs improvement.

The initial results of civil forfeiture application indicate that it solves many tasks in the fight against corruption. So, we hope that such achievements will prove a real incentive to improve the opportunities for using such a tool.

This publication was prepared by Transparency International Ukraine with the financial support of Sweden.

A small but rich sample of decisions of the High Anti-Corruption Court on the recognition of assets as unjustified shows that this mechanism needs improvement.

Andrii Tkachuk