On March 26, the ARMA presented its 2024 annual report. However, the text was not made publicly available until the second half of April, and we took the time to analyze it.

At first glance, the reports of the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (the ARMA) seem impressive: they boast billions in “identified assets,” substantial contributions to the state budget, and large volumes of asset management.

But if you dig just a little deeper, these apparent achievements begin to lose their shine. For example, in all of 2024, the Agency appointed only seven asset managers for seized property, even though many seized assets remain unmanaged.

It’s a bit like a hospital proudly reporting its outstanding care of ten VIP patients, while hundreds of regular patients in shared wards go months without basic medical help. Yes, those ten were treated perfectly, even rehabilitated to the highest standards — but can that really be called a success for an institution whose purpose is to care for the entire community?

We took a deeper dive to understand what truly lies behind ARMA’s 2024 performance figures.

At first glance, the reports of the ARMA seem impressive: they boast billions in “identified assets,” substantial contributions to the state budget, and large volumes of asset management. But if you dig just a little deeper, these apparent achievements begin to lose their shine.

Pavlo Demchuk

Tracing and identifying assets

Let’s start with the first of ARMA’s two core functions, as reflected in its name — asset recovery.

According to paragraph 5 of the preamble to EU Directive 2024/1260, an effective asset recovery system requires the “swift tracing and identification of instrumentalities and proceeds of crime, and property suspected to be of criminal origin.” This function is the first crucial step in the process of stripping criminals off their illicit profits.

Paragraph 14 of the preamble to the Directive also emphasizes the need for early identification of property, ideally at the beginning of a criminal investigation, especially assets that may be located in other jurisdictions or tied to transnational crime.

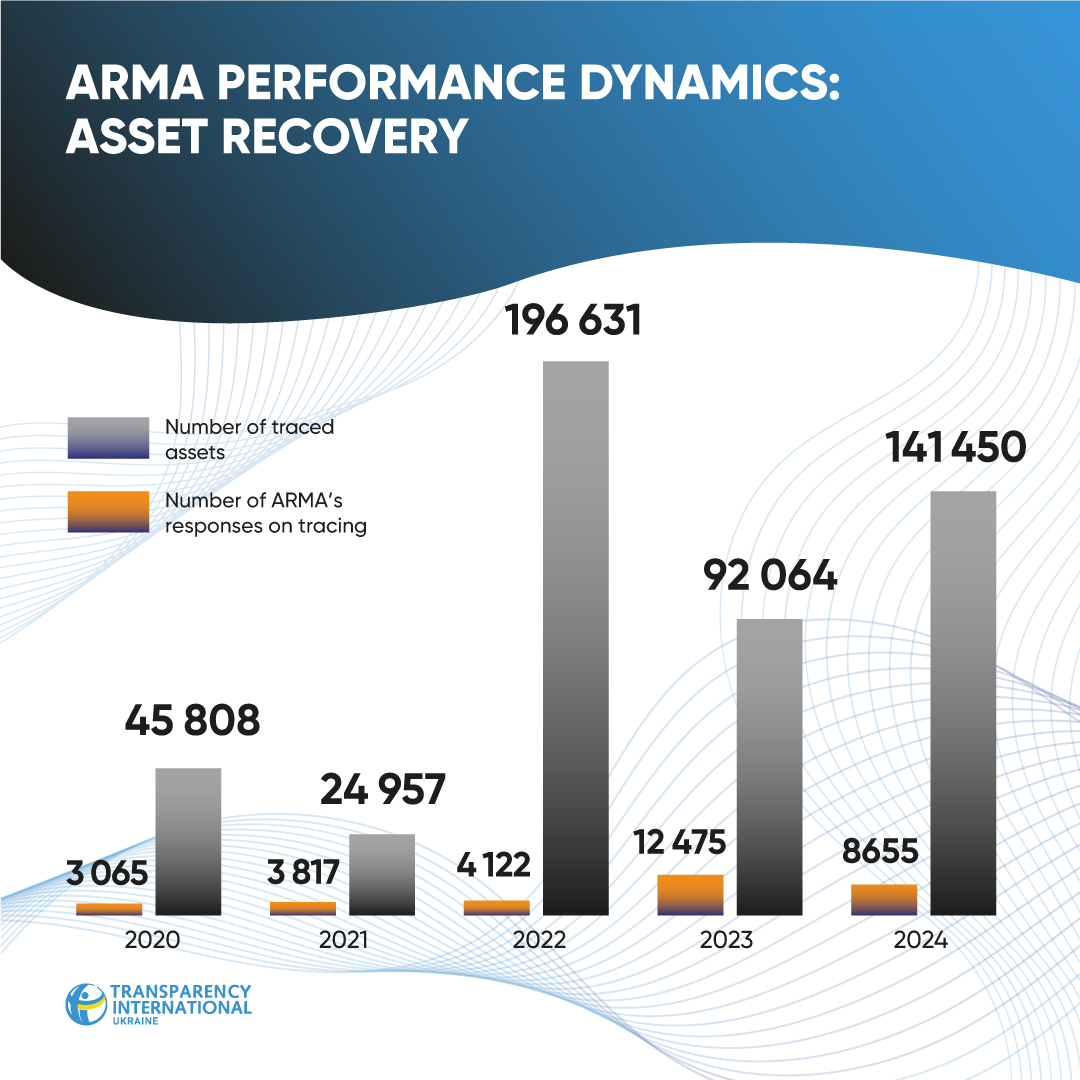

In 2024, ARMA reported identifying and tracing 141,500 assets — more than in 2023 (96,000), but far fewer than in 2022 (196,600).

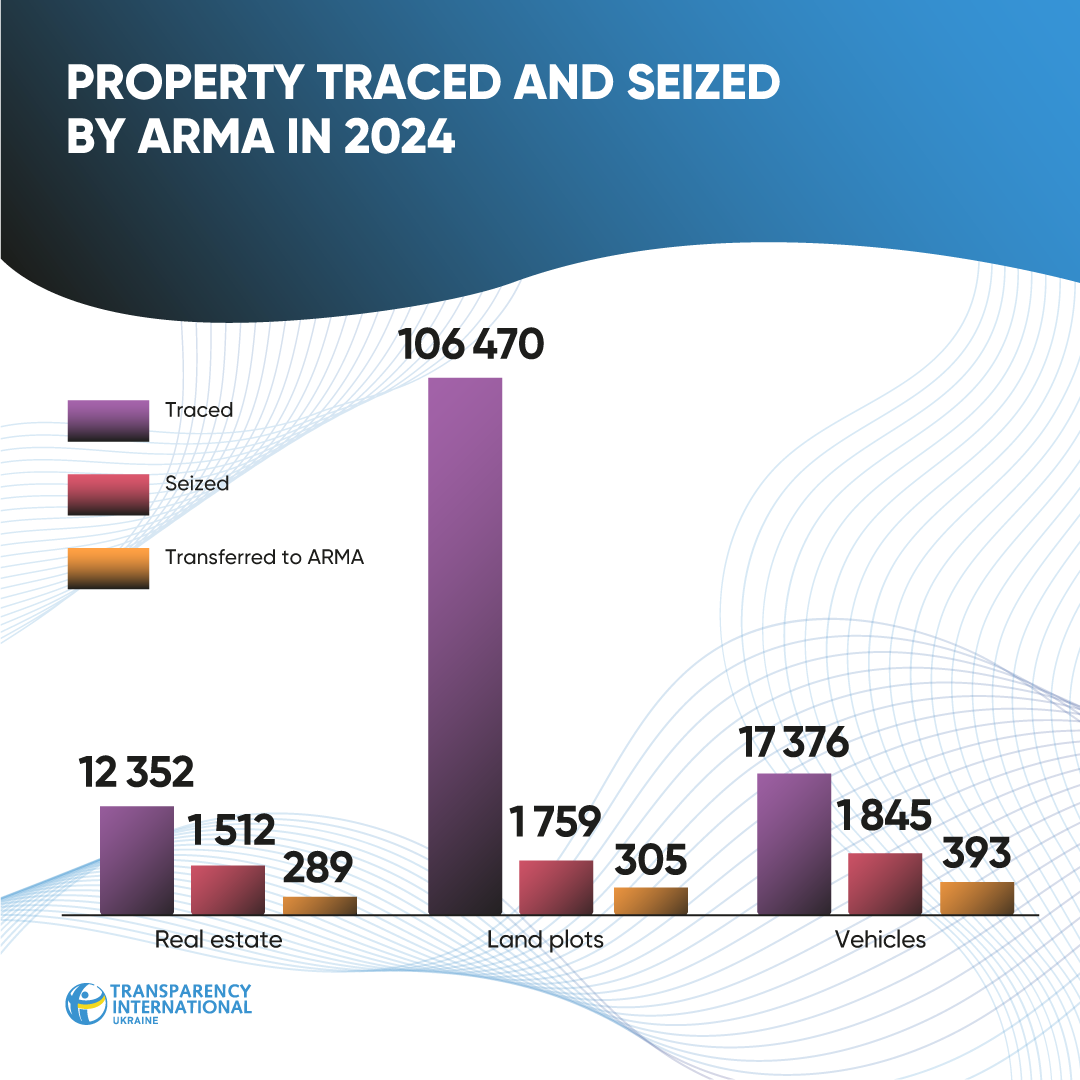

Yet it’s unclear how these numbers were compiled. The 2024 report shows that out of the total, 107,066 were land plots — an increase of 57,900 compared to the previous year. This suggests that the volume of other asset types was relatively low.

What happened to the identified assets raises further concerns. If we examine how many of them were actually seized and transferred to ARMA’s management, the figures suggest systemic flaws in data quality, and perhaps that some owners managed to transfer the assets before they were officially seized.

For example, regarding real estate ARMA reports on the identification of 12,352 properties (6,372 residential + 5,980 non-residential), of which 1,512 were seized (12.2% of those identified), and 289 were transferred to management (19.1% of those seized and only 2.3% of those identified).

At the request of law enforcement agencies, 106,470 land plots were identified, 1,759 of them were seized (1.7% of those identified), and 305 were transferred to ARMA (17.3% of those seized and only 0.3% of those identified).

Transport: The ARMA identified 17,376 units of aviation, road, rail and marine types of vehicles. However, of these, 1,845 units were seized (10.6% of those identified), and 393 were transferred to management (21.3% of those seized and 2.3% of those identified).

The situation with money is no less interesting. The ARMA reports tracing of significant amounts: €103.7 million, $79.9 million, and UAH 8,3 billion. But of these, only €2.3 million (2.2 of those identified), $14,3 million (17.9% of those identified), and UAH 163.3 million (only 2% of those identified) were seized. And even less was transferred to the ARMA’s management: €1.58 million (69.9% of those seized, but only 1.5% of those identified), € 10.6 million (74% of those seized, 13.3% of those identified) and UAH 86 million (52.7% of those seized, but critically small 1% of the total amount identified).

The data on corporate rights is even more striking. The ARMA claims to have recovered corporate rights worth UAH 34 billion, €1.2 million, and another UAH 305 million in other currencies. But the report contains no information about the seizure or management of these assets.

As we can see, only about 7.8% of all recovered assets were seized, and fewer than 3% came under ARMA’s management. And this indicates a huge gap between impressive recovery numbers and real results. While ARMA cannot directly control seizures — that’s the responsibility of prosecutors and judges — the low figures raise questions about the reliability of the data ARMA provides. Inaccurate or poorly substantiated information makes it difficult to secure seizures or transfer assets to management.

Moreover, ARMA’s public disclosure of information about identified assets, which it often promotes, may actually reduce the chances of effective seizure and management.

Only about 7.8% of all recovered assets were seized, and fewer than 3% came under ARMA’s management. And this indicates a huge gap between impressive recovery numbers and real results.

Pavlo Demchuk

Managing seized assets

Asset management is ARMA’s second core function and is critical to preserving the value of property while criminal proceedings are ongoing. According to paragraph 5 of the preamble to EU Directive 2024/1260, an effective asset recovery system requires not only their tracing and freezing but also “the effective management of frozen and confiscated property in order to maintain the value of that property for the State or for the restitution for victims.” Poorly managed assets can quickly lose their value, undermining the purpose of their seizure.

Paragraph 41 of the preamble to the same Directive underlines the need in “efficient management of entities,” such as undertakings, that should be preserved as a going concern, while taking the measures necessary to ensure that the suspect or accused person does not benefit directly or indirectly from the ongoing operations of such an entity.

Unfortunately, ARMA’s performance here is equally problematic. Despite claiming to have “unique experience and expertise in managing seized property,” the Agency shows limited results.

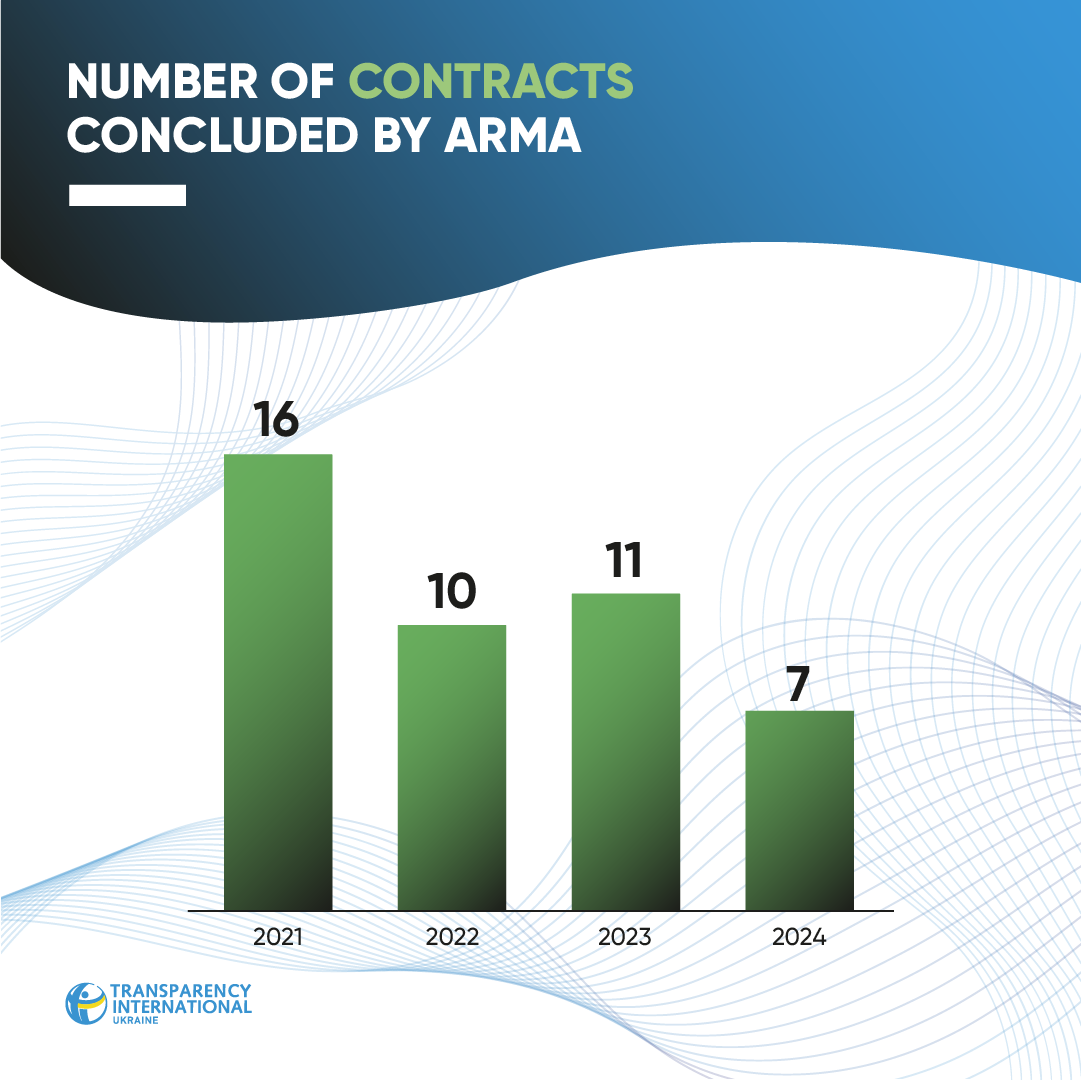

In 2024, ARMA announced 33 tenders to select asset managers, but signed only 7 management contracts. The number of signed management contracts remains consistently low: 7 in 2024, 11 in 2023, and 10 in 2022.

The Agency’s communication on these issues is also interesting. One of ARMA’s promotional posts says about 224 evaluator competition selections and 33 open bidding tenders with features. However, these efforts still resulted in just 7 management contracts.

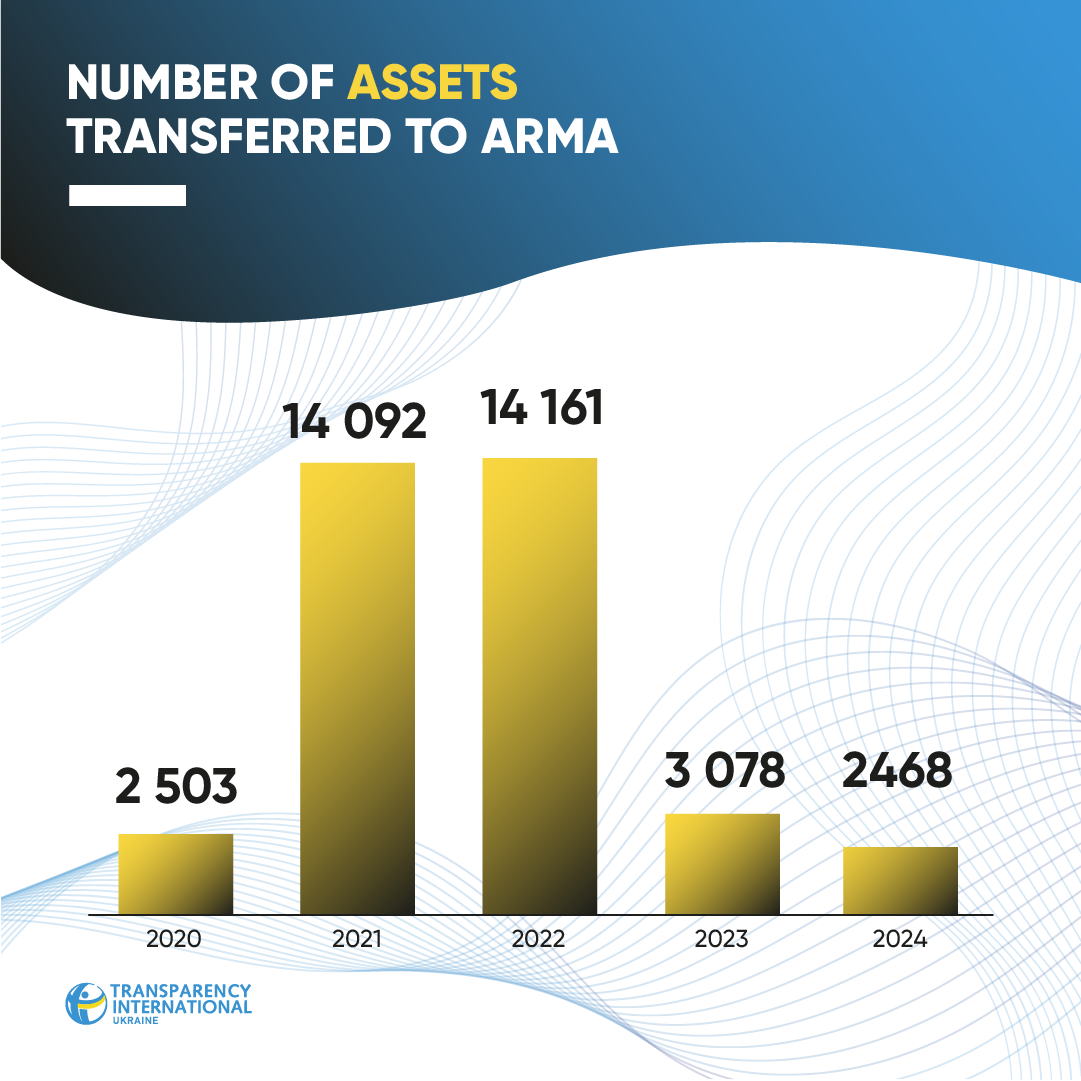

The number of assets transferred to ARMA also declined sharply — from 14,161 in 2022 to 2,468 in 2024. However, the number of on-site inspections of managers remains critically small: only 10 per year with a large number of properties under management.

Most notably, ARMA highlights UAH 1.17 billion in revenue for the budget but nearly all of that was generated by a handful of managers appointed before the current head of the agency took office. The largest contributors include Chornomornaftogaz, Ukrnafta, Ukrtransnafta, Krytex-Service, and Naftogazenergia. Together, they generated most of the amount shown by the ARMA as proceeds from seized asset management (UAH 1,139 million).

As the head of the Parliamentary Anti-Corruption Committee rightly pointed out, 88% of the UAH 1.2 billion in 2024 revenue came from just two state-owned enterprises. These included profits from fuel stations handed over to Ukrnafta (formerly GLUSCO) and assets from Ukrnaftoburinnya (73% of the total), plus dividends from shares in 26 regional gas companies managed by Chornomornaftogaz (another 15%).

What does this tell us? Many assets transferred to ARMA remain without managers for long periods. This means seized assets either continue generating income for their original owners, or deteriorate and lose value.

Of course, assigning managers to seized assets is a complex and responsible task. However, Draft Law No. 12374-d offers a sound solution, and yet ARMA strongly opposes it.

Many assets transferred to ARMA remain without managers for long periods. This means seized assets either continue generating income for their original owners, or deteriorate and lose value.

Pavlo Demchuk

***

It’s essential to understand that ARMA is not a fiscal body. Its goal is not to fill the budget, but to manage seized assets effectively. When only a tiny fraction of identified assets is assigned managers — and an even smaller number are managed properly — this points to systemic failures.

ARMA offers a textbook example of chasing performance metrics rather than fulfilling its mission. Glossy numbers in a presentation can’t hide the reality of a system that is ineffective where it matters most.

While ARMA is a critical part of the anti-corruption infrastructure, its current standards fall far short of that role. Without real reforms — from asset tracing to management — ARMA risks remaining a potentially important, but practically ineffective, institution.

To make a real difference, Draft Law No. 12374-d needs to be urgently adopted to introduce transparent manager selection and address many of the core issues that continue to hinder ARMA’s effectiveness.

Without real reforms — from asset tracing to management — ARMA risks remaining a potentially important, but practically ineffective, institution.

Pavlo Demchuk