Several months ago, the Ternopil City Council initiated a public discussion on the proposed changes to the master plan and zoning plan for the city’s territory. In a notice on the website, the city council stated that project materials in hard copy form could be accessed at the Department of Urban Planning, Architecture, and Cadastre during working hours from 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM on weekdays. No other methods were offered.

Journalists of the 20 Minutes media visited the location. Before you could see the drawing, you had to register in a log. No photos, they mentioned, due to the ongoing war, and several employees closely monitored this situation in the office.

Logical questions arise. Is it truly necessary to register a person for access to urban planning documentation, given the circumstances of martial law? Hasn’t humanity developed some form of electronic service to eliminate the need for manually recording geological data in a notebook?

The response to the initial question lies in the mayor of Ternopil’s order, mandating the city council to publish such data. Services for this already exist – these are geographic information systems that encompass all the spatial data of the city and offer significant benefits to society. We will explain why residents can have access to them even during the war.

What are geoportals?

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are information platforms designed to collect, store, analyze, and visualize spatial data. Public-accessible parts of such systems are called geoportals.

Geographic Information Systems enable cities to efficiently manage community land assets, infrastructure, economic and demographic potential. They also serve as fundamental tools for ensuring transparency.

Establishing a geoportal at the city level is a significant step towards enhancing public oversight and streamlining all procedures. The vision is that every city resident can acquire a wealth of information from the comfort of their own home using the system. One can observe the zone in which a specific development site is situated and identify the height restrictions and sanitary standards in place. The Geoportal can also provide information on what the city is being developed with funding from the public budget.

With just a few clicks, portal users can verify the grounds on which a new small structure or billboard has been erected in the city. Users can also obtain information about the closest shelter or the availability of a ramp, which is beneficial for individuals with limited mobility.

Ultimately, the Geoportal can display ongoing repair work in the city, such as the repositioning of paving stones, which has led Ukrainians to protest in various parts of the country.

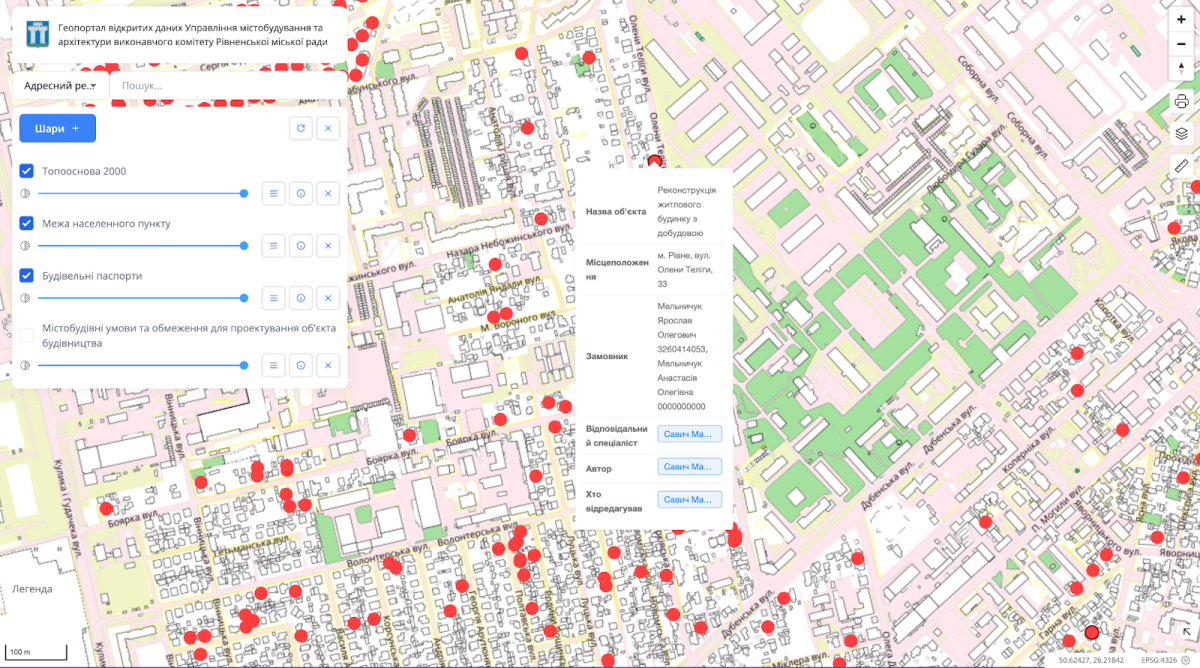

Example of a construction data sheet from the Rivne Geoportal

Developers of geographic information systems adhere to the principle of modularity, with the urban development cadastre typically forming the foundation for these systems. It encompasses general plans, detailed territory plans, an address register, urban planning restrictions, construction data sheets, and information about various types of objects (such as social institutions or historical monuments). Moreover, the city has the capability to incorporate additional modules to suit diverse preferences.

There are two primary players in GIS development in Ukraine: SoftPro and MagneticOne Municipal Technologies. There are two primary players in GIS development in Ukraine: SoftPro and MagneticOne Municipal Technologies. In December 2019, MagneticOne Municipal Technologies implemented a Geoportal in Ternopil, as previously mentioned. However, rather than accessing it directly, journalists are required to transcribe data into a notebook under strict supervision. This case, unfortunately, is not unique in Ukraine. We will further explain whether martial law genuinely prohibits the opening of geoportals.

With just a few clicks, portal users can verify the grounds on which a new small structure or billboard has been erected in the city. Users can also obtain information about the closest shelter or the availability of a ramp, which is beneficial for individuals with limited mobility.

Geoportals vs full-scale invasion

After February 24, local authorities, as well as the state as a whole, rapidly closed access to information that seemed useful to the enemy. The Association of Cities of Ukraine advocated for the closure of open data, and the Cabinet of Ministers issued a resolution permitting cities to limit the operation of registers and information systems.

However, by the summer of 2022, the “thaw” had commenced. The Ministry of Digital Transformation considered making changes to some resolutions so as not to publish only specific sets of open data. However, the government did not accept these proposals, so local authorities should continue to publish the data in full.

In 2023, the revised resolution from the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine emphasized the necessity to halt or limit the operation of information systems and registers solely in areas affected by active military operations and temporarily occupied by Russia.

It appears that cities in the rear would have the legal capacity to restore access to their geoportals, there are no evident legal grounds prohibiting them from doing so. Just like before the full-scale invasion, local governments must release 57 open data sets, five of which are directly related to urban development.

If last year Transparent Cities recommended refraining from publishing urban planning data, the current security situation in the country has prompted a change in approach. Specifically, the frequency of DDoS attacks on city council websites has markedly decreased. Therefore, if the dissemination of information can really be harmful, it should be separated and the reason for restricting access should be publicly explained. Nevertheless, the principle of “closing everything” contravenes the constitutional right of everyone to access public information.

It appears that cities in the rear would have the legal capacity to restore access to their geoportals, there are no evident legal grounds prohibiting them from doing so.

Have geoportals opened in cities now?

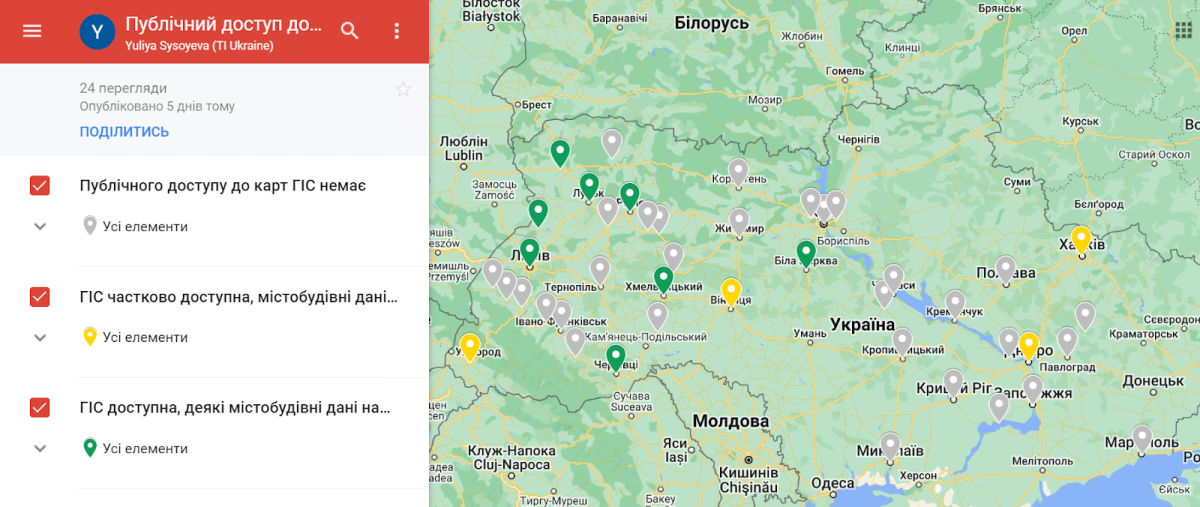

As of October 2023, a minimum of 43 participants in the Transparency Ranking of 100 Largest Ukrainian Cities have functional geographic information systems.

Efforts towards their creation and improvement continue without slowing down. Varash, Drohobych, Kovel, Pavlohrad, Poltava, Smila, and Ternopil have been implementing solutions of various scales over the past year and a half. The authorities in Kryvyi Rih actively finance the development of GIS and declare that their city is currently the leader in the number of Geoinformation system modules that have already been implemented (9 modules and 21 subsystems). In other words, GIS development programs continue to be implemented, money is allocated for their implementation, and tenders for software creation are held.

However, out of the 43 cities, only 12 offer consistent access to geoportals. Moreover, even fewer – only 8 cities – publish data that serves as the foundation for the “Urban Development Cadastre” module.

The Transparent Cities program decided to ask city councils how they motivated their decisions to open or close access to geoportals. To do this, we selected cities from two categories: with open portals (Khmelnytskyi, Kovel, Rivne) and with closed ones (Kolomyia, Mykolaiv), and sent them requests. Let’s take a closer look at some of the answers.

At present, Khmelnytskyi appears to be the most forward-thinking state in this regard. On the city’s geoportals, users can access the address register, topographic plan, master plans, detailed territory plans, territory zoning plan, construction data sheets of land plots, and urban planning conditions and restrictions for designing construction projects. Deputy Mayor Mykola Vavryshchuk informed Transparent Cities that access to the public section of GIS was restricted from the initial days of the full-scale invasion due to widespread DDOS attacks on the city council’s web resources. However, in April 2022, access was restored after special additional measures were taken to strengthen the level of cybersecurity. And nothing bad happened after that.

City zoning plan on the Khmelnytskyi Geoportal

In Rivne, the data was partially closed. Oleksandr Vorobiuk, Deputy Head of the Department of Urban Planning and Architecture of the Rivne City Council, stated that, based on the mayor’s directive, access to the city’s Geoportal data, which includes information about the location of crucial engineering networks and other defense facilities, is restricted. Everything else remains publicly available.

In Lutsk, urban planning data was initially entirely inaccessible, but it was later partially reinstated.

Nataliia Khmel, Head of Information Technologies at Lutsk City Council, commented on the situation: “We acted in accordance with the recommendations from the Ministry of Digital Transformation, as stipulated in the amendments to the government resolution. We have an email from them containing recommendations on which data sets should not be published. Basically, it’s about urban planning, as far as finding objects is concerned.”

Access to the primary drawing of the Master Plan of Lutsk was reinstated for users only after the issuance of the decree on public monitoring of land relations.

Most rear cities – from Kyiv and Zhytomyr to Kalush and Kolomyia – are not rushing to grant citizens access to geoportals that were closed after February 24, 2022.

For instance, Kolomyia Mayor Bohdan Stanislavskyi, in response to our request, stated that access to the Geoportal was restricted on February 25. In the summer of 2022, the City Council received a letter with recommendations from the Ministry of Digital Transformation, as mentioned earlier.

While the government did not adopt these proposals, meaning no obligations were imposed on the city council, public access to the Geoportal was entirely blocked. It is claimed that selectively hiding sensitive data in GIS is not feasible. “Since the web resource is not the sole source of access to the urban planning documentation of the city of Kolomyia, due to the vulnerability of the web resource to cyberattacks since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the decision was made to restrict the functioning of the portal,” said Bohdan Stanislavskyi.

Home page of the Kolomyia Geoportal as of November 27, 2021

(source: Wayback Machine – Internet Archive)

This answer is doubly surprising. Initially, the Geoportals of Rivne and Kolomyia were developed by the same SoftPro company, utilizing the principle of modularity. Nevertheless, Rivne succeeded in concealing sensitive data on their geoportal, while Kolomyia could not. Secondly, it turns out the same paradox as in Ternopil. The Kolomyia City Council acknowledges the obligation to disclose public urban planning data, yet concurrently restricts access to the Geoportal, compelling residents to attend personal receptions at the City Council.

What is the threat of closed urban planning data?

The situation in cities is different, and the arguments of city councils regarding closed geoportals are also different. This suggests that the stance of the central government on the publication of data that may be classified as information with restricted access is inconsistent.

And everything would be fine, but simultaneously, urban planning documentation is undergoing significant changes. Just this year, the media reported on the development of alterations to the general plans and zoning plans in Kyiv, Kropyvnytskyi, Sumy, Ternopil, and Uzhgorod. Journalists drew attention to the fact that even before the pandemic, the draft general plans were not submitted to public hearings for years. And presently, with access to documents significantly restricted due to martial law, and individuals who could partake in discussions engaged in conflict or migration, city councils have become notably more proactive.

Under such conditions, the probability that the decision will not be made in favor of the community increases dramatically. For instance, when the designated purpose of land plots transitions from a recreational area to a multi-apartment residential development zone. This was evident in the case of Kropyvnytskyi, where three ten-story buildings were constructed in the green zone near the Inul River in the city center. There are also plans to reduce parks and squares in Ternopil – journalists are raising concerns.

How can one advocate for the reopening of geoportals?

What should active residents and journalists do? Demand that city authorities study the practices of cities like Khmelnytskyi, Rivne, and others, which have limited public access on geoportals solely to data concerning engineering networks and critical infrastructure facilities.

When engaging with local authorities, it is crucial to emphasize that Resolution No. 835 still mandates, as it did before the war, the publication of 57 data sets. Additionally, Resolution No. 236 from May 2023 specifies that it is imperative to cease or limit the operation of information systems and public electronic registers exclusively in frontline or temporarily occupied territories.

Even during martial law, geoportals in rear cities can provide tangible, substantial benefits. Specifically, these include ensuring transparency in public urban development activities, fostering collaborative problem-solving with the community, enhancing the comfort and safety of life for all, and improving the overall quality of the urban environment.

When there is no data, the needs and capabilities of researchers, companies, and residents are ignored. The operation of businesses and the development of new socially beneficial services are becoming increasingly challenging. Consequently, cities are restricting the capacity to operate more effectively under martial law.

Conversely, open data enhances the level of transparency and accountability, directly influencing trust in local authorities, both among Ukrainians and the international community.

This publication was created by Transparency International Ukraine as part of its project implemented under the USAID/ENGAGE activity, which is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by Pact. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Pact and its implementing partners and do not necessary reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.