Content

- About the project

- Selection of projects for recovery

- Financing

- Procurement

- Construction

- Conclusions and recommendations

In late April 2023, the government launched a project to restore a number of settlements that had been destroyed as a result of the war. It was expected that, unlike the object-by-object reconstruction, which was launched simultaneously, the project would provide for an integrated approach to the planning and complete transformation of these settlements. This approach has not been used before in the short history of rebuilding our country from the consequences of aggression, so the project has become experimental.

Last year, more than half a billion hryvnias was allocated from the national budget for the project out of the planned 3.3 billion, and the regional branches of the Agency for Restoration, responsible for its implementation, launched the works. However, in 2024, funding for the experiment ceased, and the project became one of the reasons for the discord between the government and the Agency.

We decided to find out what the conditions of the experiment were, at what stage the restoration of selected settlements is, and whether there are prospects for its further implementation.

Selection of settlements

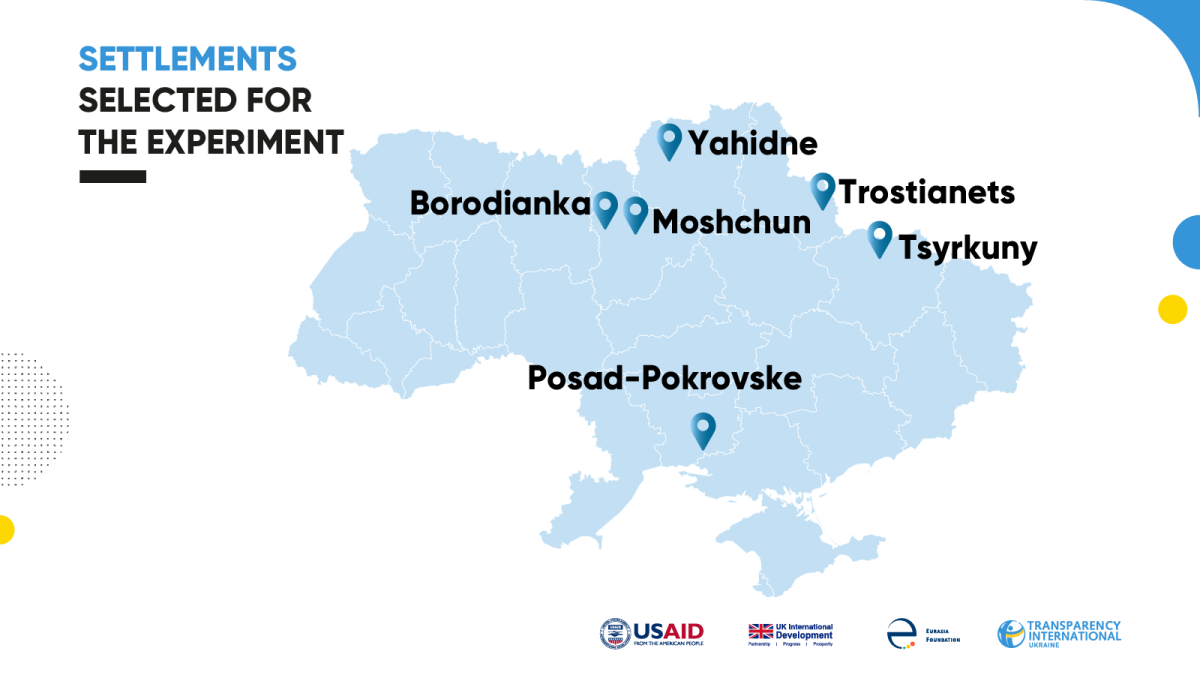

Back in April 2023, the government identified six settlements where the restoration was to take place as part of an experimental project. It covered:

– Borodianka and Moshchun villages in the Kyiv region;

– Trostianets city in the Sumy region;

– Posad-Pokrovske village, located on the border of the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions;

– Tsyrkuny village in the Kharkiv region;

– Yahidne village in the Chernihiv region.

The conditions for these settlements to be included in the list for comprehensive restoration were different. For example, Yahidne and Tsyrkuny were included in the list on the initiative of the regional military administrations (RMAs), while Trostianets was included on the initiative of the Office of the President. Probably, for the same reason, Moshchun and Posad-Pokrovske were included in the list: shortly before the experiment was launched, the president had visited these settlements.

The determining criterion for selection should have been the significant level of settlement destruction. But it differed greatly among the selected ones.

The Moshchun village was one of the most destroyed settlements in the Kyiv region. According to the RebuildUA project, 2,000 buildings were completely or partially destroyed due to active hostilities—this is more than 70% of all buildings.

In Borodianka, Kyiv region, 1,534 buildings were destroyed or damaged—almost all key administrative infrastructure objects, some social and housing facilities. The State Emergency Service estimated the level of destruction in the central part of the village at 90%, but the overall level of destruction reached 15%.

Despite this difference, both settlements were selected to participate in the experiment. At the same time, the level of destruction in at least four other settlements in the Kyiv region (Irpin (48%), Horenka (22%), Hostomel (38%), and Makariv (30%)) was higher than in Borodianka.

In Trostianets, Sumy region, the central part of the city was badly damaged, and the area of the railway station and bus station was completely destroyed. 829 buildings were damaged, and 134 of them were destroyed. However, the overall level of destruction was slightly higher than 4%.

In Tsyrkuny, Kharkiv region, the occupiers completely destroyed 15% of all buildings and damaged more than 1,100 residential infrastructure objects. In Posad-Pokrovske, this figure reached 940, and in Yahidne, Chernihiv region, 117 real estate objects were damaged and destroyed. Unfortunately, there is no information on the overall level of destruction in these settlements.

In general, the list of settlements participating in the experiment demonstrates the lack of a unified approach to their selection. In some cases, preference was given to settlements with a significantly lower level of destruction, and the orders “from above” contributed to the inclusion of some in the list. Given that the number of destroyed settlements in Ukraine continues to grow and probably not all will be rebuilt, after the experiment is completed, the government cannot do without developing criteria and procedures for determining the settlements that will be subject to comprehensive restoration in the future.

Experiment conditions

The government determined the key principles of the experiment by its resolution in April 2023. According to it, works on the restoration of settlements are planned to be completed in 2025, and they are to be financed from the Remediation Fund. Since the procedure for using the resources of this fund entails only the object-by-object restoration, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a separate procedure to implement the experimental project.

The coordinators of the project were the Ministry for Restoration and the Agency for Restoration. The latter was empowered to initiate the allocation of budget funds for the project and approve the lists of objects to be restored in the selected settlements. The regional branches of the Agency were designated as procuring entities of works and services. Thus, the Agency for Restoration de facto became responsible for the implementation of the experiment.

In addition to regional recovery services, regional military administrations also became participants in the project. Notably, the government determined that the participation in the experiment by local self-government bodies was optional. According to the conditions of the experiment, the lists of objects to be restored within the settlement were formed not by local self-government bodies (LSGBs) but by RMAs according to their proposals. However, neither the procedure nor the deadline for their submission, nor the requirements for considering or not considering such proposals, are provided for by the procedure approved by the Cabinet. This approach contains risks of both disregard for the interests of the community on restoration issues and excessive powers of RMAs, which, at their own discretion, might not include a particular object in the list of restorations.

The fact that the administrations are not the last link in the procedure for approving the lists of objects for restoration adds doubt to the idea of RMA mediation in the process of comprehensive restoration of settlements. The relevant functions are performed by the Agency for Restoration and the government. Therefore, LSGBs could independently submit projects for analysis to the Agency. This would contribute to the principle of speed of recovery declared by the government, both in the formation of lists and in their possible revision.

Before the start of the experiment, it was stated that the reconstruction would be carried out comprehensively and according to new principles. According to the prime minister, one of the main principles is to build back better—rebuild an object better than it was. However, it is not clear exactly how the principle of build back better will be implemented in practice. The fact is that the procedure does not provide for conditions for the mandatory improvement of the quality or technical characteristics of damaged or destroyed objects during their restoration. The situation is similar with the comprehensive approach to reconstruction. The procedure does not provide for either the mandatory development of works by the procuring entity or of a plan for the restoration of the settlement by LSGBs, or compliance with the already developed planning documents for the restoration of regions and territories provided for by law.

When forming the lists of objects to be restored, both the RMA and the Agency for Restoration should consider the priority of meeting the primary needs of the population. However, the government did not approve the criteria for prioritizing needs. Neither did it consider the possibility of applying the methodology, which, although advisory in nature, was used by the Ministry for Restoration for project-by-project reconstruction. Therefore, prioritization is formally provided for by the procedure, but the conditions for its application (and its application in general) in each case depended on the decision of the body that formed the list.

The situation with the restoration of private property was also ambiguous. The procedure provided for such a possibility but did not regulate the procedure for the owners applying with proposals for restoration, as well as its conditions (for example, regarding the area or amount that will be allocated for the restoration of destroyed real estate). This is crucial for those whose property was affected, as they faced a choice: to receive compensation within the framework of the eRecovery program or to restore housing within the framework of the experimental reconstruction project. In addition, the procedure did not consider the interests of the owners when planning the restoration of housing, since it was assumed that such decisions would be made by the procuring entity of the works, that is, the relevant restoration service.

In November 2023, the Cabinet of Ministers amended the procedure: it limited the total area of destroyed housing, which can be rebuilt as part of the experiment, to 140 sq.m., and provided for the possibility of making planning decisions by the owner to restore their home. But at the same time, the procedure for submitting proposals on the restoration of private property remains unresolved.

The assessment of the conditions for the implementation of the project indicates that they are not sufficiently detailed. This entails risks associated with both the planning of settlement reconstruction as a whole and prioritizing individual restoration objects within their limits. The government concentrated the functions of making key decisions related to comprehensive recovery in the hands of the Agency for Restoration and its regional branches, while not providing for due consideration of the interests of community representatives.

Notably, according to the results of the analysis, most of the risks specified in this section were not realized in the course of experiment implementation. It is important to focus on them to avoid their occurrence in the case of applying the comprehensive restoration approach to other settlements in the future. The identified deficiencies are described in more detail in the following sections.

Selection of projects for recovery

The process of selection and approval of projects for the recovery of settlements took more than 3 months and was completed in August, when the government approved the relevant list.

It contained 32 projects, which, according to the Agency for Restoration, included 306 objects to be restored.

Approved objects to be restored by category:

- 268—housing;

- 10—social infrastructure;

- 17—logistics infrastructure;

- 7—administrative buildings;

- 4—housing and municipal services objects.

In accordance with the conditions of the experiment, the lists of objects for recovery were to be formed and approved based on the priority of meeting the primary needs of the population. However, it is not known whether the Agency for Restoration used prioritization with the objects to be restored and what its criteria were because it did not respond to the relevant inquiry. It should be noted that, for the most part, the approved objects were subject to the requirements defined by the conditions of the experiment. But there are also those whose priority seems rather doubtful.

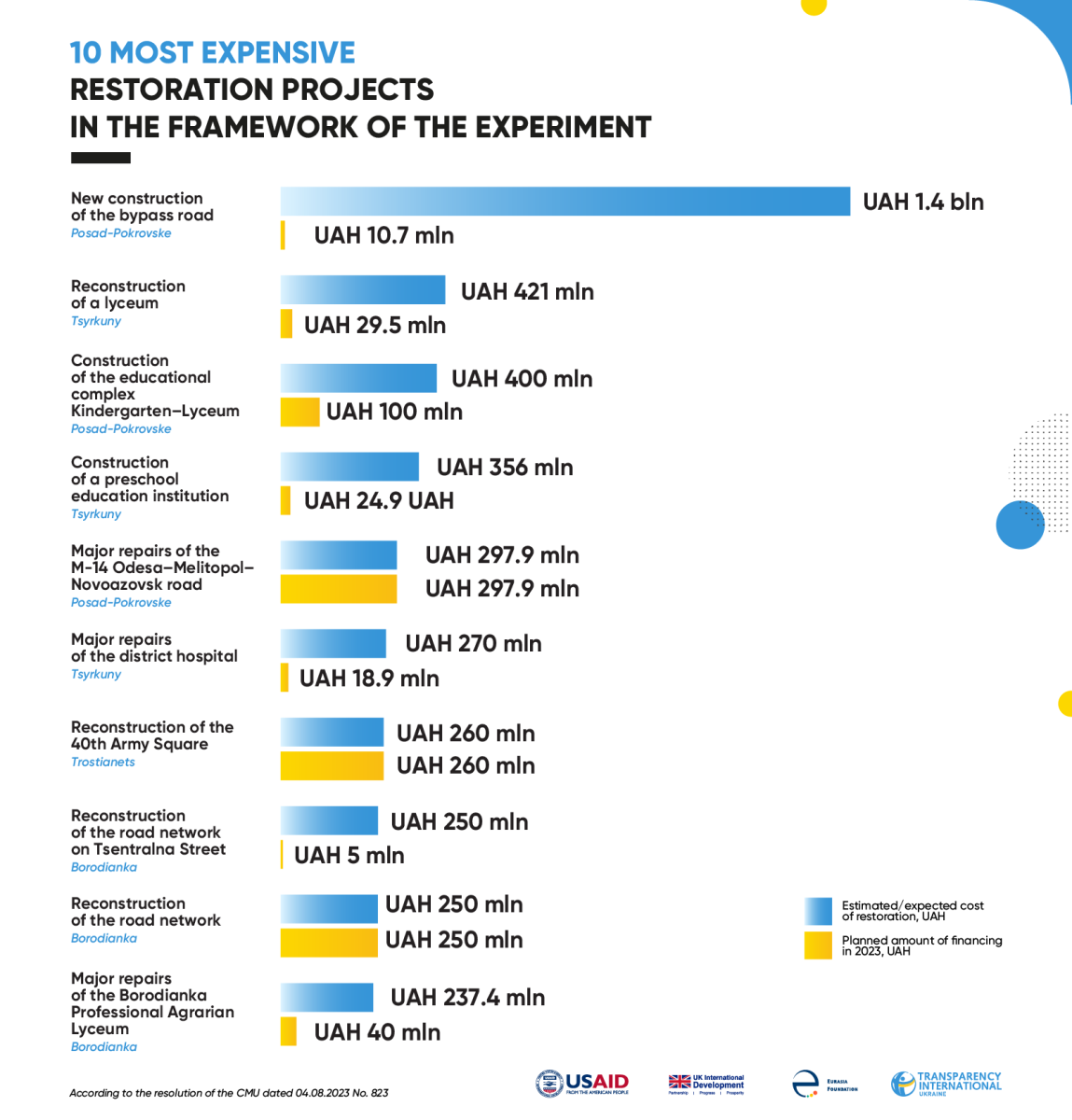

One of them is the project to restore the 40th Army Square in Trostianets with the expected cost of UAH 260 million. As part of the project, according to the RMA, 21 privately owned commercial real estate objects (shops) were covered by the reconstruction at the expense of budgetary funds. The project was included at the suggestion of the city council, but it was probably more facilitated by the mention in the letter of the head of the Presidential Office instructing the Prime Minister to work on the restoration of the destroyed station and station square;

Not without road repairs. In total, the list includes 4 projects for the “recovery” of roads of national importance: three sections of the highway H-12 Sumy-Poltava for the comprehensive restoration of Trostianets, as well as two sections of the M-14 Odesa-Melitopol-Novoazovsk highway for the restoration of Posad-Pokrovske. Major repairs of two sections of the H-12 Sumy-Poltava highway, which are located between Trostianets and Klymentove, were planned before the beginning of the full-scale invasion within the framework of the Great Construction presidential program. In February 2021, a corresponding procurement transaction was even carried out, but in June 2023, the contract was terminated due to the inability of the contractor to perform the works. As for the restoration of Posad-Pokrovske, the list included the construction of a new bypass section of the road on the north-eastern side of the village, with an estimated cost of UAH 1.46 billion. In general, almost UAH 2 billion was planned to be spent on the construction and repair of roads as part of the comprehensive restoration of settlements.

Objects approved for recovery were mostly based on proposals received by regional administrations from affected communities. In certain cases, some objects were screened out at the stage of forming the list. In particular, the Kharkiv RMA prioritized the restoration of the social and administrative infrastructure of the Tsyrkuny village over the residential one. Another part of the objects got excluded from the list when it was approved with the Agency for Restoration. For example, an extracurricular educational institution, the department of social protection, and the branch of Oschadbank in Borodianka; the community center and a lyceum in Posad-Pokrovske were not included in the list for reconstruction. However, the final number of objects to be restored in Posad-Pokrovske (128) increased in comparison with the number of objects submitted (75), mainly at the expense of housing.

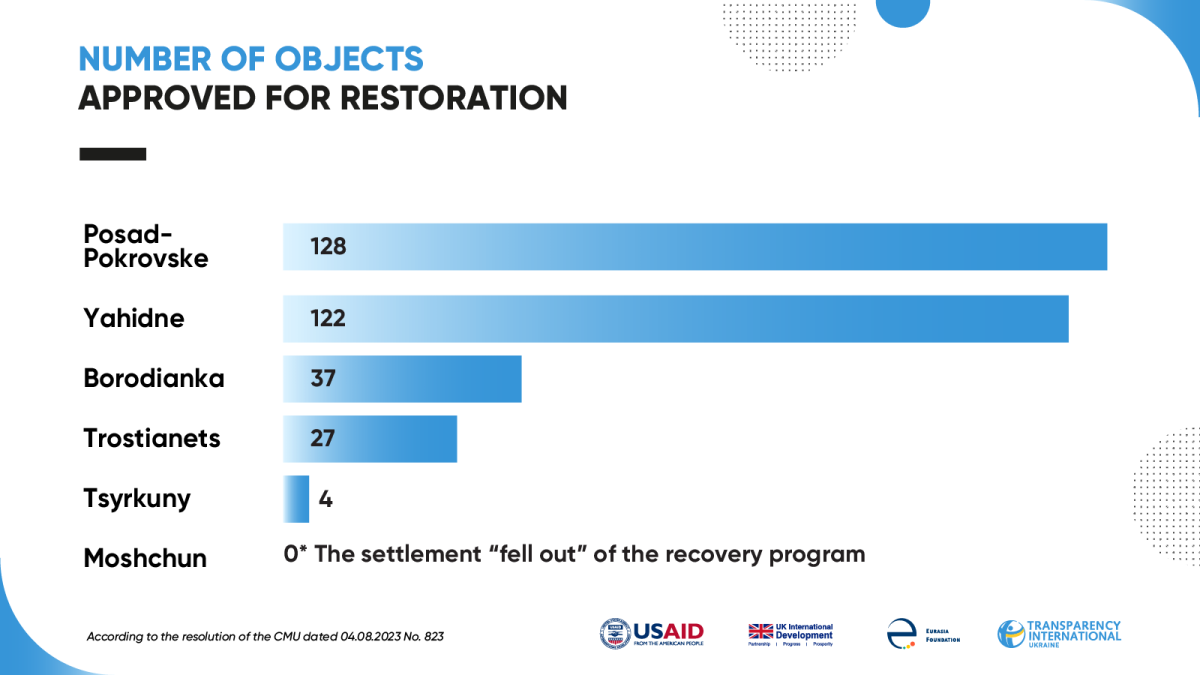

The result of the screening of some objects by the RMA and the Agency was the imbalance in their number in relation to the settlement. In Posad-Pokrovske and Yahidne, the approved list included 128 and 122 objects, respectively, more than 90% of which were residential buildings. In Borodianka, three times fewer objects were chosen for restoration—37. The smallest number of objects was approved for Tsyrkuny—only 4.

As for Tsyrkuny, the Kharkiv RMA submitted a list that included only social and administrative infrastructure: the village council, a hospital, a lyceum, and a kindergarten. The administration planned to restore the rest of the objects at the expense of the Remediation Fund too, but through object-by-object reconstruction. On the one hand, such a solution involves the use of several mechanisms for the restoration of a settlement at once, which allows for avoiding the risk of suspending the implementation of one of them (spoiler alert: that’s what happened to the comprehensive restoration). Can the reconstruction of four infrastructure objects be considered a comprehensive restoration of the settlement? Hardly. In this case, it seemed appropriate to replace the settlement with one in which a significant percentage of infrastructure was affected and the restoration of which was not planned under other mechanisms. The corresponding idea was even voiced by the head of the Kharkiv RMA; however, this was due to constant shelling of the village. But the issue of replacing Tsyrkuny did not go beyond the discussion at the level of the regional administration.

Even more “dramatic” was the situation with the restoration of Moshchun. First, the Kyiv RMA submitted a list of objects, which included 108 private residential buildings, for approval by the Agency for Restoration. But, according to the head of the Agency, the prime minister did not see the point in rebuilding housing as part of the experiment, given the possibility of restoration through the eRecovery program. The Agency supported such an idea.

Subsequently, the Kyiv RMA reported that the restoration of the village is hampered by outdated urban planning documentation, and its updating is impossible since the village military administration lacks appropriate powers. So, in the end, in the final list, which the RMA submitted for approval, there were no restoration objects in Moshchun. Thus, the settlement “fell out” of the recovery program while formally remaining its “participant.”

The situation with Moshchun clearly demonstrated the lack of a unified approach to the selection of projects for restoration within the framework of the experiment. While more than a hundred private residential buildings were approved for restoration in Posad-Pokrovske and Yahidne each, no such project was approved for Moshchun. This is an additional confirmation of the need to formulate clear criteria and requirements for the application of the comprehensive recovery mechanism in the future.

Financing

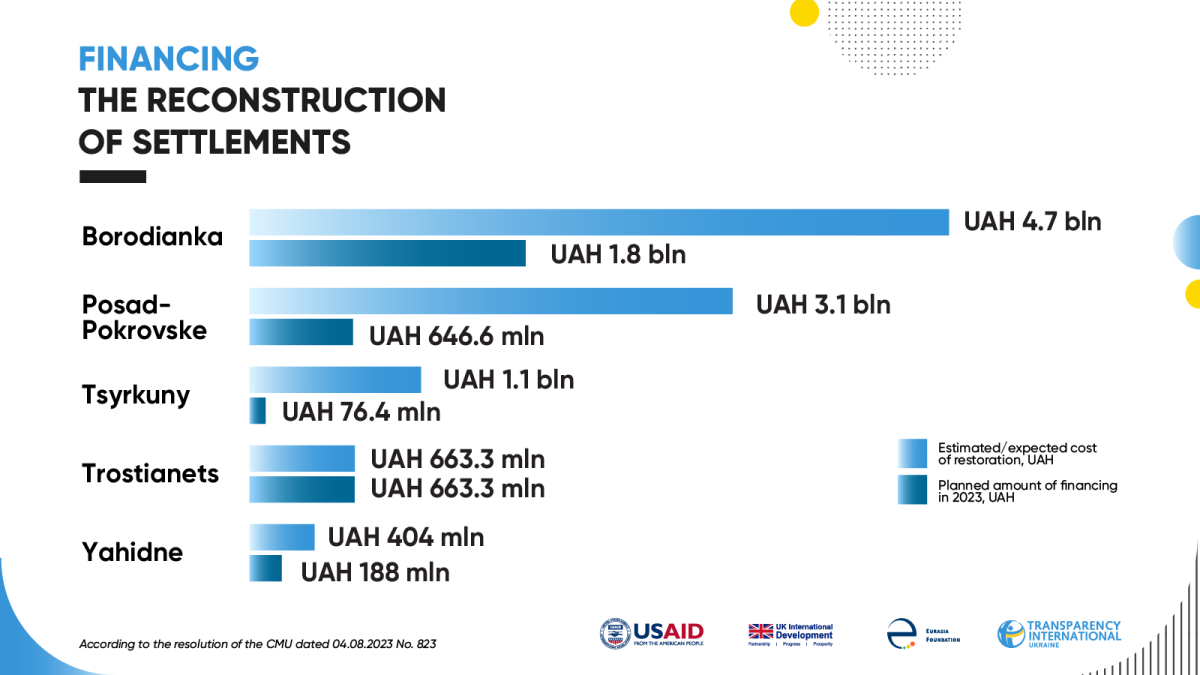

The main and, currently, the only source of funding for the project was the Remediation Fund. On August 4, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine allocated UAH 3.350 billion for the budget program to restore settlements in 2023.

In accordance with the conditions of the experiment, information on the expected cost of works was to be added by the RMA to each object included in the list and subject to restoration. However, in practice, only two out of five regional administrations, those of Kharkiv and Sumy, provided information on the expected cost of restoration works. Other RMAs ignored the need to determine the expected cost of works and, citing the lack of such information in the proposals from LSGBs, provided an approximate cost of works. In the end, the total amount of necessary funding for the implementation of works under approved projects was determined based on these amounts, which reached UAH 9.6 billion.

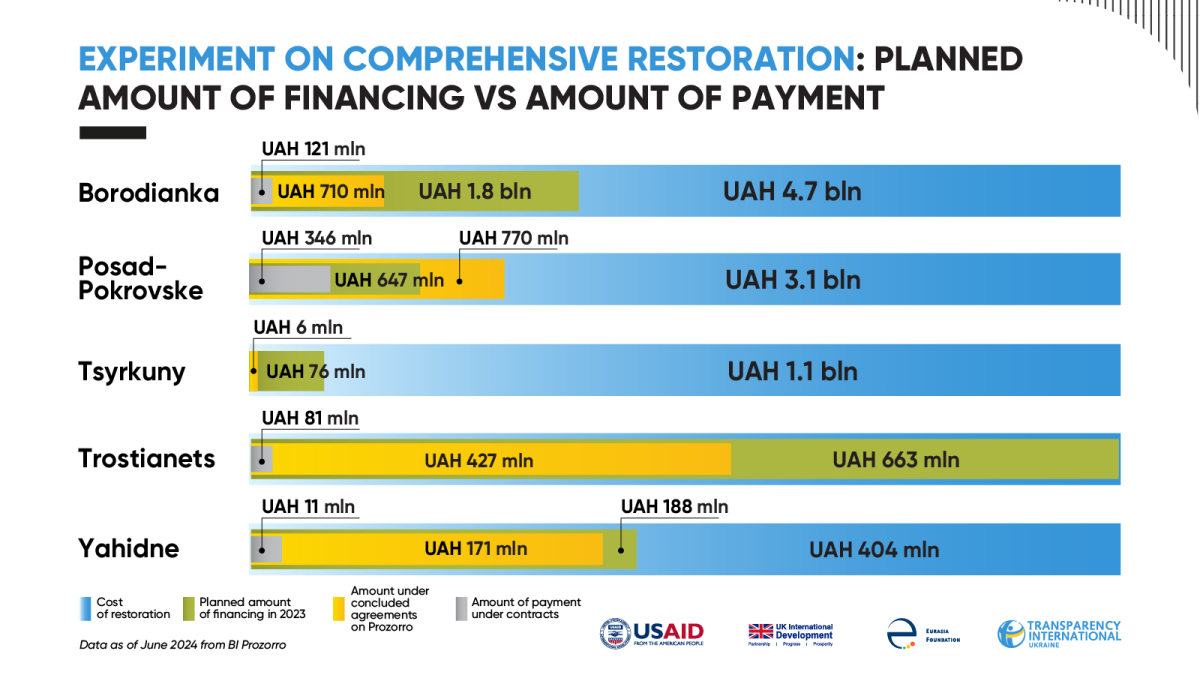

Trostianets was the only settlement in which restoration projects were planned to be fully funded in 2023. Instead, only 7% of the expected cost of projects was allocated for the restoration of Tsyrkuny last year. The costliest was the restoration of Borodianka (UAH 4.7 billion), and the fewest funds were planned for Yahidne (UAH 404 million).

According to the distribution contained in the government resolution, the amount allocated in 2023 should have been sufficient to fully cover the costs of design and construction works for at least 129 objects and to finance the commencement of works in regard to the rest.

However, the regional recovery services were able to start procurement procedures only after the approval of the budget program passport on September 14. As a result, by the end of 2023, the costs of the experimental project for comprehensive restoration—advance payments and payment under the service acceptance certificates—amounted to only UAH 559 million out of the planned UAH 3.350 billion.

In 2024, the funding situation worsened. According to the Agency for Restoration, in early February, it sent a request for the allocation of the remaining unused funds in the amount of UAH 2.8 billion to continue the reconstruction works. In March, the government reallocated the rest of the resources from the Remediation Fund for 2023, but did not agree on the allocation of funds for comprehensive recovery. As of July 22, the project remains without funding.

Procurement

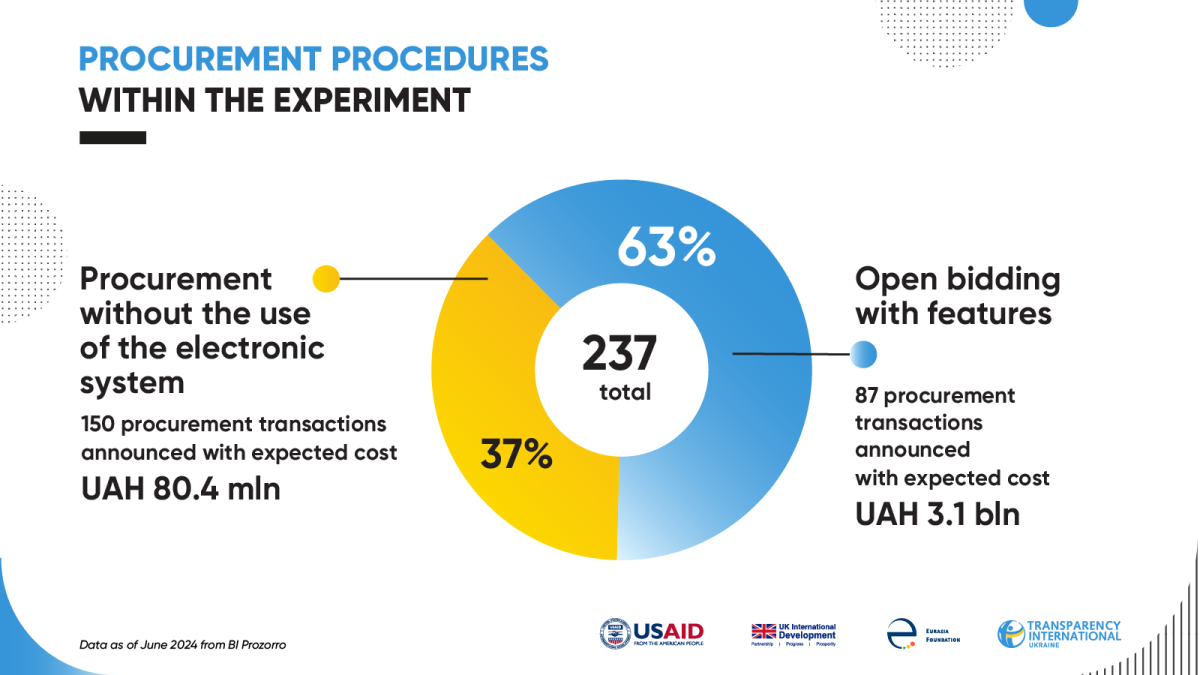

To implement the experimental project, the functions of the procuring entity of construction works were entrusted to the regional services for restoration and development of infrastructure. The relevant powers were granted to the services in the Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, Kharkiv, and Kherson regions. According to BI Prozorro, as of June 2024, 237 procurement transactions were announced as part of the experimental project for the restoration of settlements.

150 lots (63% of the total) constituted non-competitive procedures. The item of the contract, for the most part, was the development of project documentation and services for technical/author’s supervision over construction. In value terms, non-competitive procedures accounted for 2.5% of the total expected cost of procurement.

87 lots (37%) were held at open bidding with features—the main procurement procedure for the period of martial law. These lots account for 97.5% of the total expected cost.

Of the total number of lots, 5% were unsuccessful (automatically canceled due to lack of bids, rejection of all bids, or canceled by the procuring entity).

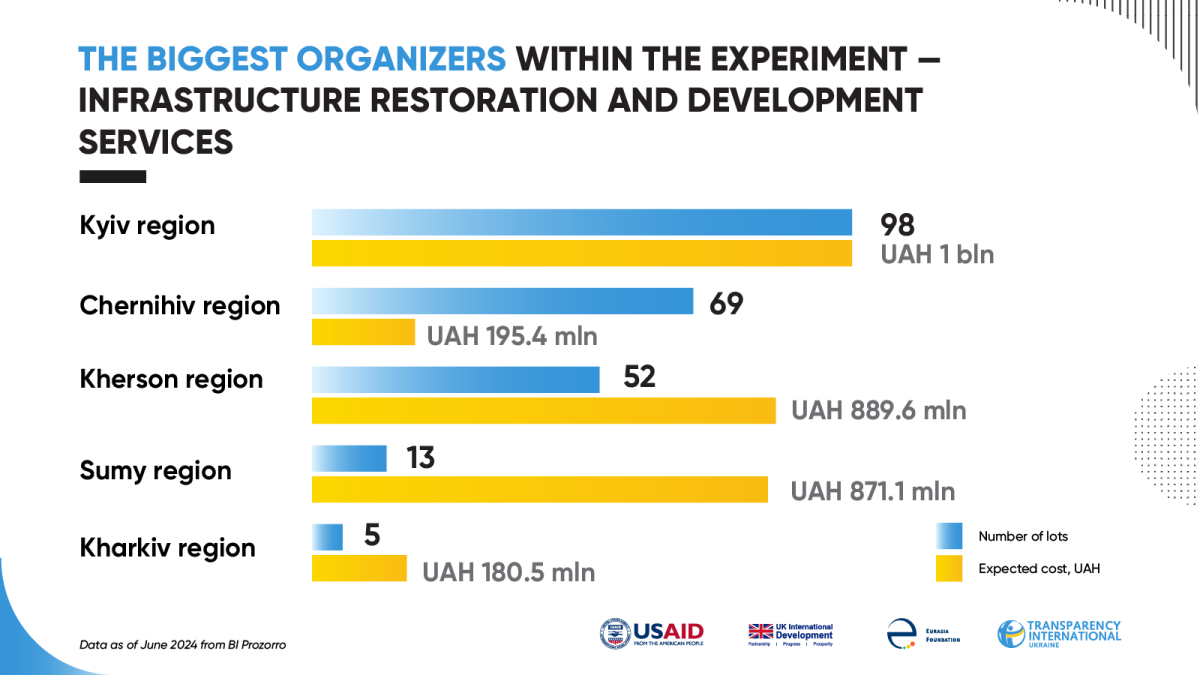

The highest number of procurement transactions was announced by the restoration service in Kyiv Oblast—8 (the expected cost is UAH 1 billion); the restoration service in Chernihiv Oblast came in second—69 (the expected cost is UAH 195 million); and the restoration service in Kherson Oblast came third—52 (the expected cost is UAH 889 million).

On average, 3.6 participants submitted bids to open bidding with features, which is twice as high as the average level of competition on Prozorro. The maximum number of participants that submitted bids to the procurement transaction is 9. All of them competed for a contract in the tender for major repairs of the road network in Posad-Pokrovske.

The most serious competition was observed in the procurement transaction of the Kyiv restoration service, the lots of which, on average, were attended by 4 participants. In some cases, competition was twice as high as the average:

- 8 participants—major repairs of an apartment building on 4 Velyka Street in Borodianka.

- 7 participants—major repairs of the Borodianka archive building.

The lowest level of competition was observed at the bidding of the Sumy Restoration Service, whose procurement was attended by an average of 2 participants. On average, 3–3.5 participants attended the tenders of the other services.

Due to high competition, the level of “nominal savings” (the difference between the expected cost and the amount of the concluded contract) averaged 21%. The highest percentage of “savings” was observed with the Kyiv service, whose tenders provide for the highest competition level.

More than 70% of all contracts concluded were for the restoration of two settlements—Borodianka (UAH 709 million) and Posad-Pokrovske (UAH 769 million). The smallest amount of expenses falls on Tsyrkuny—UAH 6 million. For this settlement, five tenders were held for a total amount of UAH 180 million. A procurement transaction for major repairs of the Tsyrkuny district hospital, with an expected cost of UAH 33 million, was unsuccessful due to the rejection of all bids. According to the results of the tender for the reconstruction of the Tsyrkuny Lyceum, an agreement was concluded for UAH 114 million, which was subsequently terminated due to lack of funding.

According to the Unified Portal for the Use of Public Funds, the amount of payments under contracts reached slightly more than 11% of the amount under concluded contracts. Over the past year, works and services were paid for as part of the Borodianka project in the amount of UAH 120 million, Trostianets—UAH 80 million, Posad-Pokrovske—UAH 345 million, and Yahidne—UAH 10 million.

Distribution of costs by types of works/services

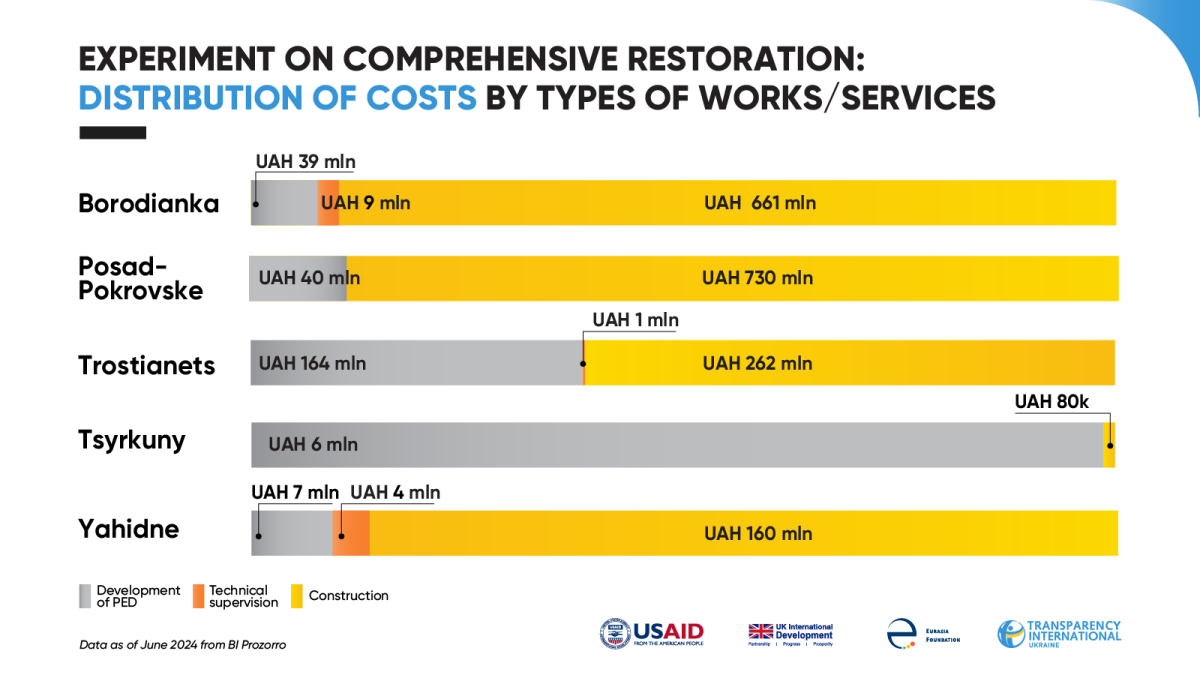

New construction and major repairs account for 87% of all concluded contracts (UAH 1.8 billion), another 12% are the costs for developing project documentation and related works / services (UAH 225 million), and 1% are technical and designer supervision services.

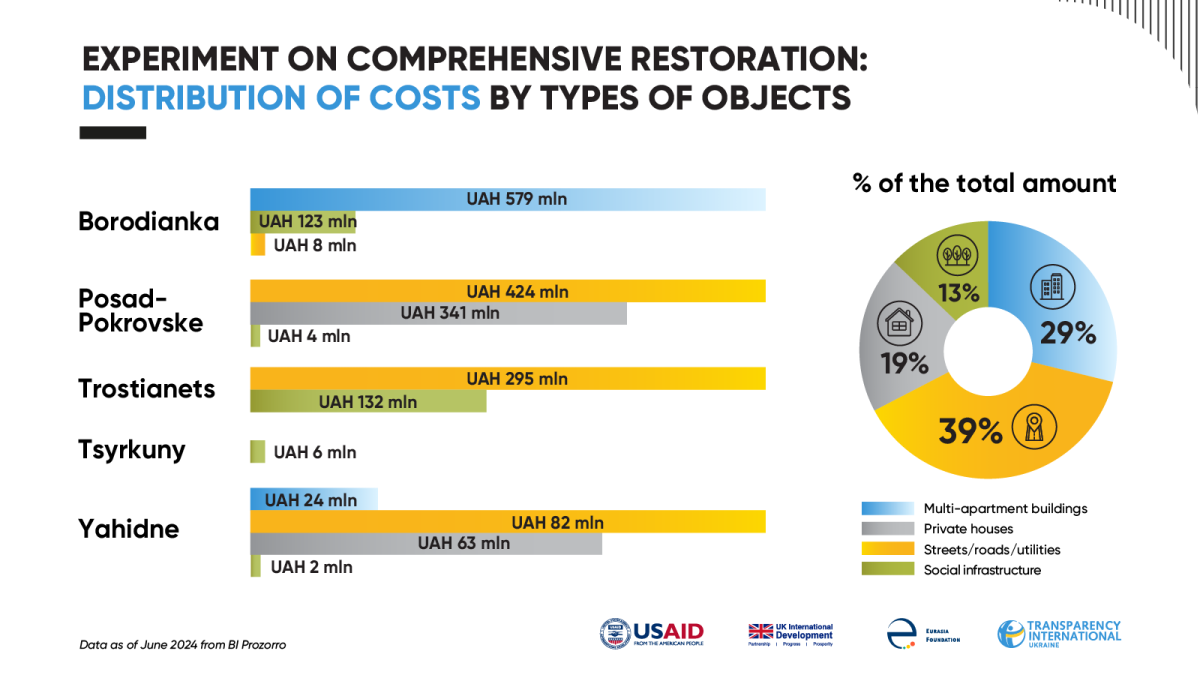

Distribution of costs by types of objects

The largest part of the contracted amounts out of UAH 809 million (39% of the total amount) falls on the restoration of engineering and road (including roads of national importance) networks. Posad-Pokrovske accounts for half of all expenses in this category.

28% (UAH 602 million) of expenses fall on the restoration of apartment buildings. The project provides for the reconstruction of 29 apartment buildings in Borodianka and another 17 in Yahidne.

The restoration of private houses accounts for UAH 404 million, which is almost 20% of the total amount of contracts. The project provided for the reconstruction of 101 private houses in Yahidne and 120 houses in Posad-Pokrovske.

Another UAH 268 million (13%) accounts for the reconstruction of social infrastructure facilities (educational, medical institutions, administrative buildings).

Analysis of the prices for materials in the estimates showed that, in general, the prices set by the contractors in the estimate were market prices. But there were also deviations that were rather random, not systemic. In particular, for two procurement transactions (1, 2) for the reconstruction of private houses in Posad-Pokrovske, the selling price for reinforcements was set at the level of UAH 39,500 per ton (after accruing the value added tax, the final price for the procuring entity will be UAH 47,000 per ton, while in the market, such reinforcements can be purchased from a warehouse at a price of UAH 34,100 per ton, including VAT), which exceeded the average price in Ukraine by a third. As a result, the potential overpayment following the procurement of reinforcements alone could amount to more than UAH 527,000. However, the type of contractual price in these procurement transactions is firm, so the procuring entity will not be able to simply adjust the cost of materials in the service acceptance certificates.

Notably, the State Audit Service monitored 23 procurement procedures (27% of the total number of open tenders) conducted as part of the experimental project. Of these, in 9 cases, the financial control body found violations, which mainly concerned the non-rejection of tender proposals that were subject to rejection or the non-compliance of the tender documentation with the requirements of the law.

Construction

Last year, the Agency for Restoration started working only five months after the adoption of the resolution on the implementation of the experimental project. The reasons for the delay were the lengthy process of selection and approval of recovery projects, as well as the approval of funding on the part of the government. At the same time, according to the agency, at the end of 2023, works were launched at 186 objects, and the average level of readiness of all objects was 24%.

But as of mid-June 2024, there has been no dramatic progress in the implementation of the experimental project. According to the restoration services:

– project documentation was developed for 260 objects (85%);

– construction works are ongoing at 211 objects (69%);

– construction works have been completed at 1 object (0.3%).

Borodianka

The list approved by the government included 37 objects for the restoration of Borodianka. 29 of them are multi-apartment residential buildings that are subject to major repairs, reconstruction, or new construction. The restoration list also includes:

– Borodianka Professional Agrarian Lyceum;

– the city post office;

– the community center;

– the building of the village council, its archive, and an employment center;

– a dormitory on Naberezhna Street;

– a road network on Tsentralna Street.

These projects are only a small part of the destroyed and damaged infrastructure of the village. The Kyiv RMA reported that more than 600 such objects were subject to restoration. The administration proposed that the Agency also include the building of the military commissariat, Oschadbank, and the Borodianka Center for Children and Youth’s Creativity in the first phase of the comprehensive restoration, but the objects were not approved.

In 2023, more than UAH 1.7 billion was allocated from the Remediation Fund to finance the comprehensive restoration of Borodianka. At the expense of these funds, it was planned to fully cover the costs of restoring the buildings of the village council, its archive, and almost 40% of residential buildings, as well as to finance the commencement of works on the remaining objects.

Borodianka Village Council acted as the procuring entity of the development of the object restoration concept. In particular, it carried out the procurement of services for the development of a preliminary design for the restoration of Tsentralna Street. In August, the executive committee of the local council approved the pre-design works, which contained unified stylistic solutions for finishing the facades during the reconstruction of objects.

According to the Restoration Service of the Kyiv region and the Kyiv RMA, as of June:

– procurement of services for the development of project documentation was announced for 34 objects;

– project documentation was developed and a comprehensive examination was carried out in regard to 24 objects;

– procurement of construction works has been announced in regard to 23 objects;

– works at the 10-15% level have been completed in regard to 16 objects.

Thus, the construction works were completed in regard to none of the objects in Borodianka.

Trostianets

During the Russian occupation, the city hospital, residential buildings, railway station, and station square were significantly destroyed in Trostianets. A decision was made to restore the medical institution and housing through the mechanism of object-by-object reconstruction. The station and the square were included in the list of projects for comprehensive restoration. This list also includes major repairs of three sections of the H-12 Sumy-Poltava road, two of which are located between Trostianets and the neighboring village of Klymentove.

Foreign and Kyiv-based architects responded to the idea of developing a concept for the restoration of the area with railway and bus stations in Trostianets. Local media even reported on public discussions of the reconstruction project. However, it is unknown whether any of the options was finally approved: there is no information about it in open sources.

In total, UAH 663 million was allocated to finance the “comprehensive restoration” of the city in 2023. These funds should have been sufficient to cover the costs of restoring all these objects. However, last year, only UAH 80.6 million was spent—12% of the allocated budget.

According to the restoration service of the Sumy region, as of June, services for the development of project and estimate documentation (PED) and construction were purchased in regard to 3 projects (reconstruction of the station and repair of the road). The exception was the project for the reconstruction of the station square. First, problems arose with the transfer of the rights to the construction procuring entity regarding the shops located on the square and privately owned. In the end, the functions of the procuring entities were transferred to the restoration zervice, but another problem arose—the lack of funding.

The Sumy RMA reported that the level of project implementation in June was only 7.2%. Due to the lack of funds in 2024, works on the objects were suspended, as was the development of project documentation for the station area.

Yahidne

The smallest in terms of total funding was to be the restoration of Yahidne in the Chernihiv region. The settlement is the second in terms of the number of approved reconstruction objects—there are 122 of them in total. But 96% of them are projects for major repairs of residential buildings, the costs of which are the lowest among other restoration projects.

As part of the experiment, the following objects were subject to restoration in Yahidne:

– a club library;

– a school;

– a road network;

– a pump room;

– multi-apartment (17) and private (101) residential buildings.

The local authorities thoroughly approached the issue of restoring the settlement. In particular for this purpose, a plan for the comprehensive restoration of the village was developed, which was approved based on the results of public hearings.

The estimated cost of the restoration of Yahidne was determined at the level of UAH 404 million. In 2023, UAH 188 million was provided for the costs associated with the reconstruction of the village infrastructure. But only UAH 10.6 million was spent that year—6% of the planned amount.

As of June, the restoration services in the Chernihiv region:

– announced procurement of services for the development of project documentation in regard to 15 objects;

– developed and examined project documentation in regard to 11 objects;

– announced procurement of construction works in regard to 10 objects.

Construction of 9 objects continued in June, but none of the objects were rebuilt. In addition, the restoration of another 20 objects is effectively blocked due to the non-transferred rights to the construction procuring entity from private owners regarding residential buildings and apartments.

Tsyrkuny

Tsyrkuny is one of the most affected villages in the Kharkiv region and, at the same time, the most problematic settlement within the experimental reconstruction project. The village is located 25 km from the border with Russia, and immediately after the launch of the experiment, the intensity of community shelling increased. In such circumstances, there is not only the question of security, but also that of the economic feasibility of restoring the destroyed objects.

In early summer last year, the RMA started talking about the possibility of replacing Tsyrkuny with another settlement of the region for reconstruction within the framework of the government project. However, locals opposed such an idea; for them, the experiment was the only hope for the restoration of the village, so soon, the replacement issue was removed from the agenda.

Only four objects were planned to be rebuilt in Tsyrkuny:

– the building of the village council (in place of which an administrative services center was to appear);

– the district hospital;

– a kindergarten;

– a lyceum.

Notably, Tsyrkuny was the only settlement in which the concept of recovery was developed at the request of the restoration service. At the same time, the procurement of the service took place without the use of the Prozorro system, and the source of funding was the funds (maintenance costs) of the Kharkiv Restoration Service. According to it, the developed concept was approved by the decision of the local council.

UAH 76.4 million was planned to be allocated for the reconstruction of Tsyrkuny in 2023—the smallest amount among all settlements participating in the experimental project. But not a single hryvnia of it was used.

The Restoration Service announced the procurement of services for emergency recovery works in regard to the Tsyrkuny Lyceum and the district hospital. According to the results of the bidding, only the contract for the reconstruction of the lyceum was concluded, which, however, was terminated due to lack of funding. As of June, the development of project documentation was ongoing regarding two other objects—the village council building and the preschool institution.

Posad-Pokrovske

Posad-Pokrovske in the Kherson region is a settlement with the largest number of approved restoration projects (128). As in the case of Yahidne, more than 90% of them relate to the reconstruction of private housing. The list also includes:

– a kindergarten-lyceum;

– the building of the village council and the security center;

– an outpatient clinic;

– gas, water and electricity supply systems;

– road network;

road section.

The restoration of Posad-Pokrovske was the first and only case in the experimental project, where the restoration service used more than half of the allocated funding for 2023, and the amount of the funds spent (UAH 345.5 million) exceeded the total costs under the rest of the settlements.

In addition, the only object in regard to which construction works were completed as part of the experiment was one of the restoration projects of Posad-Pokrovske. The Restoration Service in the Kherson region did not provide an answer to our inquiry, but it is probably related to the major repairs of the M-14 highway, passing through the settlement. However, almost UAH 298 million was used to restore the road section, while none of the residential buildings under the project was restored. This was the reason for the regional authorities to accuse the Agency. However, the head of the department reported that the reconstruction of housing was complicated by the need to transfer the rights to construction procuring entities from the owners (this problem was also characteristic of other settlements). According to him, as of June, restoration works continued in all 120 homes, but with the cessation of funding in 2024, construction slowed down or stopped altogether.

Conclusions and recommendations

It was expected that the implementation of the experimental project would help to find a new, effective solution for the restoration of settlements, the infrastructure of which was significantly affected by Russian aggression and required an integrated, rather than object-by-object, approach to reconstruction. The project was tasked with simultaneously ensuring transparency, efficiency, consistency, and swift recovery. However, during the first 8 months of the project implementation, it became clear that it was easier said than done in practice.

The results of the first year of the experiment can hardly be considered successful: out of more than 300 planned restoration objects, only one was completed, which was not the primary need. The government and regional authorities blamed the Agency for Restoration and its head for the failed project, given the low performance. He, in turn, referred to the long delays on the part of the government and the lack of funding.

In the end, the political upheavals that accompanied the implementation of the project were one of the reasons for the dismissal of the Agency’s head. However, it is important to find out what went wrong and what should be considered for the future because we cannot do without a mechanism for comprehensive recovery.

In our opinion, the successful first phase of the project (implementation was expected from 2023 to 2025) was hampered by several problems:

- Gaps in the experiment conditions. The selection of restoration objects to implement the experiment for the restoration of settlements lasted more than three months. During this time, regional administrations collected proposals from local governments of affected settlements, formed lists based on them, which were then submitted to the Agency for Restoration for approval. At the same time, some RMAs repeatedly submitted updated lists, and some lists were returned for revision, which required a repeated appeal to the local authorities for updated proposals. Moreover, not only the participants of the experiment, but even representatives of the Cabinet and the Office of the President intervened in the selection and approval of projects. Overall, this slowed down the process and shifted the actual launch of the project to the autumn of 2023.

Apart from the political component, this situation was caused by the lack of clear requirements and criteria for the eligibility of restoration projects in the Procedure for the Implementation of the Experimental Project (the same type of object was approved or not approved in the list of different settlements), as well as the inclusion of intermediaries (RMAs) in the procedure for selecting projects. Interestingly, it was the representative of the local authorities—the mayor of Trostianets—who opposed the statements by the heads of RMAs and the government and did not agree with the negative assessments of the agency’s activities when its head reported on the results of the restoration.

In addition, the lack of a unified approach to the selection of restoration projects led to the fact that the reconstruction of Moshchun was almost completely excluded from the experiment.

- Funding delays. The lengthy process of selecting restoration projects directly affected the financing of the experiment, since the allocation of funds for its implementation in 2023 took place simultaneously with the approval of the list of these projects—on August 4. At the same time, the approval of the passport of the budget program took place in mid-September. As a result, the regional restoration services were able to start procurement only five months after the official launch of the experimental project and three months before the end of the budget year.

During this time, the restoration services conducted at least 237 procurement transactions for the development of project and estimate documentation, construction, and technical supervision. The level of nominal savings (the difference between the expected cost and the amount under the concluded contract) for procurement averaged 21%. As of the end of 2023, UAH 558 million was transferred to contractors—17% of the allocated funds for the corresponding year.

With the end of the budget year, there was a need to obtain additional funding to pay for the works performed and services provided in 2024. However, as of June, the balance of unused funds in 2023 was not allocated by the government, despite the fact that funds were reallocated to other areas in March. Lack of funding led to the suspension of work by contractors or even the termination of contracts.

- Government procedures and political instability. According to the latest report of the Agency for Restoration, the institution sent a request for the allocation of the remaining unused funds in the amount of UAH 2.8 billion to continue the reconstruction works in February 2024. As of June, the draft order on financing was under consideration in the Cabinet of Ministers Secretariat but was not considered for more than a month due to the failure of the relevant government committee on recovery, headed by the former Vice Prime Minister for Recovery of Ukraine, to hold meetings. However, the dismissal of Kubrakov should not have caused a collapse in the work of the committee because, according to the existing distribution of powers, he should have been replaced by another deputy prime minister—Fedorov.

- Failure to transfer the rights to construction procuring entities. The implementation of the experimental project was also hampered by problems associated with the reconstruction procedure. In accordance with the conditions of the experiment, the entities of state or municipal property management, as well as the owners of private property, had to transfer the functions of the construction procuring entity to the restoration services. But in practice, private owners had long ignored this duty and even opposed it. Moreover, as of June 2024, the restoration of part of residential real estate in Yahidne, Chernihiv region, is further blocked due to the non-transferred rights to the construction procuring entity.

Analyzing the circumstances and results of the first year of the project for the comprehensive restoration of settlements, we come to the conclusion that the unsuccessful launch of the project is due to the lack of its proper legal regulation and obstacles on the part of both the government and the project’s participants. In view of this, the government should reconsider its position on the effective suspension of funding for the experimental project. Moreover, for some settlements, it is a “safety ring” needed to restore life in them. But understanding the conditions in which we all find ourselves now, the government must allocate the financial resources efficiently, considering all other priorities of the country.

Taking into account that comprehensive reconstruction has prospects for use as a mechanism for the recovery of cities, towns, and villages of Ukraine and that the relevant provisions are already included in draft legislative initiatives, we recommend:

- Developing criteria and approving the procedure for determining settlements that will be subject to comprehensive restoration, in order to exclude the possibility of making subjective decisions in the process of selecting such settlements or intervening in it.

- Determining the criteria for the eligibility of objects for the purposes of comprehensive restoration and providing for their mandatory priority in accordance with approved methods.

- Excluding intermediaries (regional state (military) administrations) from the procedure for selection and approval of objects subject to restoration, as in the case of the object-by-object recovery.

- Appointing leaders for the coordinating bodies of the experimental project—the Minister Communities, Territories and Infrastructure Development of Ukraine and the Head of the State Agency for Restoration and Infrastructure Development.

This research was prepared within the framework of the Digital Transformation Activity, funded by USAID and UK Dev.

This research is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Transparency International Ukraine and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

This research has been funded by UK International Development from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Authors: Andrii Shvadchak, Yaroslav Pylypenko and Borys Nesterov