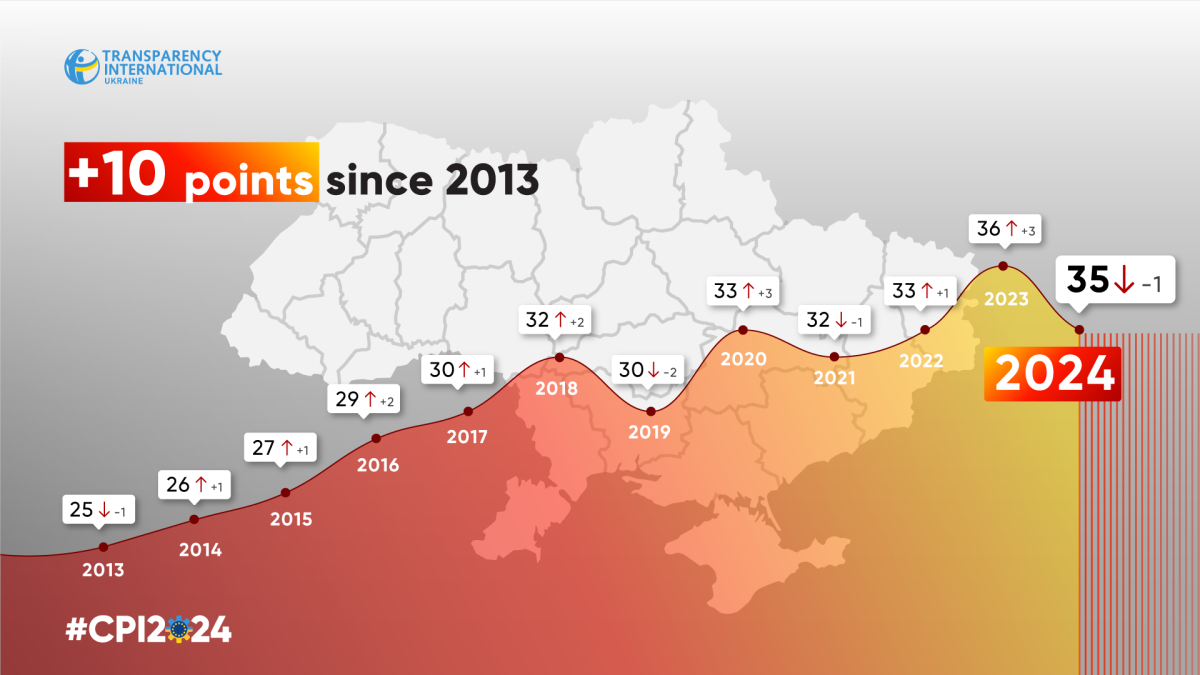

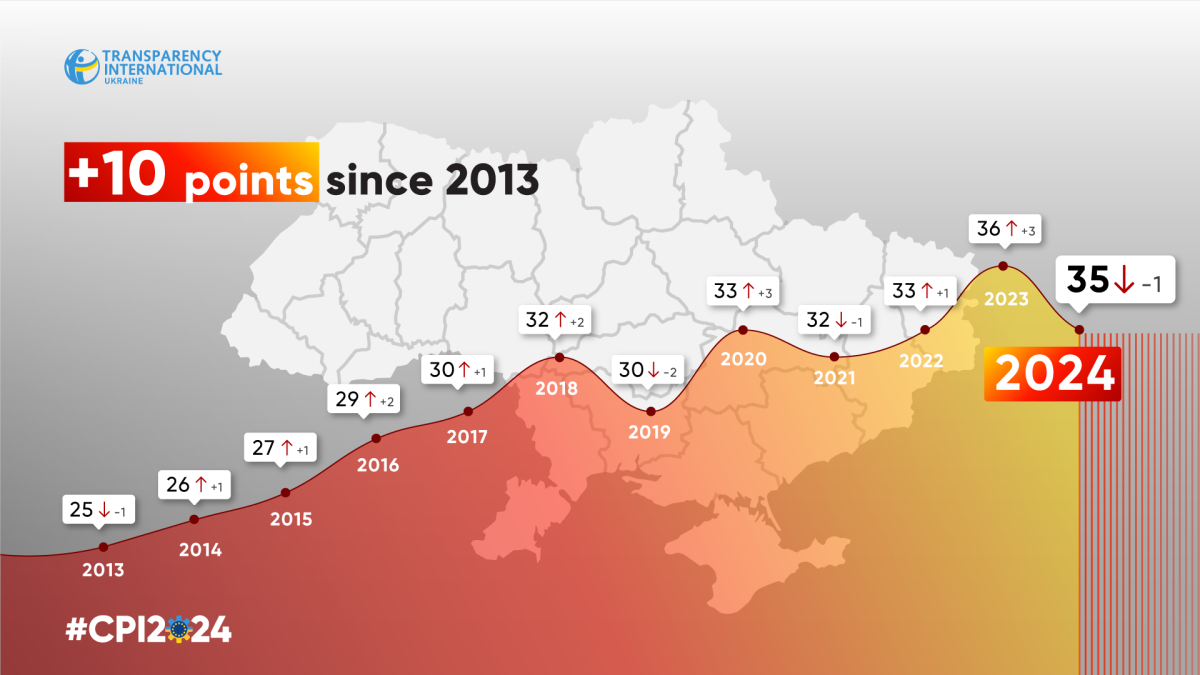

Ukraine currently stands at 35 points out of a possible 100, ranking 105th among 180 countries in the Corruption Perception Index. In other words, over the past year, we lost 1 point in Transparency International’s study.

We will examine in more detail what contributed to this decrease, who conducted the evaluation, and how we can overcome this stagnation.

How does the Index work, and what do our scores indicate?

This year, Ukraine’s CPI score has fallen below the global average of 43 points, indicating that our country is perceived as more corrupt.

However, overall, the decline in Ukraine’s indicators is consistent with broader regional trends in corruption perception. Moreover, although the one-point drop falls within the Index’s margin of error, it still signals a certain stagnation and a relatively formal approach to reform implementation. What does “margin of error” mean?

The CPI is a comprehensive study, which results in a lag between when events occur and when they are reflected in the Index. This delay is primarily due to the vast amount of data collected and processed about the country, which requires significant time to analyze. The Index is based on 13 studies conducted by various reputable institutions, each covering different periods. While each source focuses on slightly different aspects and evaluates a varying number of countries, combining these diverse estimates ultimately yields a balanced result.

For example, Ukraine was evaluated in 8 out of the 13 studies. Notably, half of these studies covered only events in 2023, while the others focused on the period up to September 2024. Therefore, many events that took place in 2024 will be more reflected in the next Index.

In addition, this year, Transparency International adjusted how original research indicators are converted to the 100-point CPI scale, which also affected the final country results.

Throughout the previous year, scandals involving top officials were regularly reported. Journalists from Bihus.Info not only identified SSU employees who organized surveillance on them, but also exposed leaks at NABU. International media covered a scandal involving possible corruption in the restoration efforts in Hostomel, and almost daily, new allegations of bribes in MSEC emerged in the news. But it is precisely because the current Index only covered a subset of these events that Ukraine’s decline turned out to be so insignificant.

The discrepancy between the Index results and actual events is a common phenomenon. For example, in Serbia—which also lost one point this year—numerous national protests against government corruption have persisted since November of last year amid the growing influence of the local president and an increasing power imbalance. Another example is Georgia, where the CPI score remained unchanged despite street protests against the election results beginning in October, and despite authorities with ties to kleptocratic networks deciding to suspend European integration altogether.

The Index is based on 13 studies conducted by various reputable institutions, each covering different periods. While each source focuses on slightly different aspects and evaluates a varying number of countries, combining these diverse estimates ultimately yields a balanced result.

Why was Ukraine scolded and praised?

Despite changes within the margin of error, a systemic negative trend is emerging in the study’s results. According to experts, Ukraine’s performance declined in five of the eight studies, namely:

- Country risk rating by the analytical department of The Economist (18 points), which evaluates budget transparency, misuse of funds, bribery, and appointments to public sector positions;

- S&P Global Insights’ country risk rating (32 points), which assesses the risks of bribery in import/export activities, government contract procurement, and general business operations;

- PRS Group’s International Risk Survey (33 points), which focuses on nepotism and patronage, suspicious links between politics and businesses, the exchange of services, and the secret financing of political parties;

- Varieties of Democracy’s survey of Corruption Index experts (33 points), which focuses on corruption in the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of power;

- World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey (40 points), which focuses on the distribution of public funds and bribery.

Therefore, to sum up, in many cases our country has performed worse in research focused on political corruption. From this perspective, procurement scandals in the defense and energy sectors, revelations of leaks at NABU, the controversial appointment of Olena Duma as the head of ARMA despite public warnings, and other similar incidents in recent years may have had a negative impact. Moreover, as noted earlier, new cases of government pressure on journalists and activists have been recorded over the past two years.

At the same time, three other studies recorded slight improvements in Ukraine’s scores, helping to partially offset the overall decline:

- Nations in Transit Report by human rights defenders at Freedom House (37 points), which evaluates bureaucracy, protection of whistleblowers, and the implementation of anti-corruption legislation;

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index (51 points), which highlights efforts in preventing corruption, as well as media and legal prosecution of corrupt officials;

- Global Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index (34 points), which evaluates the abuse of official positions for private gain.

In the latter study, where we improved our score by 1 point, the judicial sphere showed the most significant positive change. This improvement is likely attributable to several developments, including the detention of former Supreme Court head Vsevolod Kniazev in May 2023, the resumption of the HCJ in January 2023 and the HQCJ in June 2023, and the initiation of a competition for the Constitutional Court, among other measures.

According to the Bertelsmann Foundation—which recorded a 2-point increase for Ukraine—the processes of digitalization that reduce corruption opportunities, along with the partial de-oligarchization of the country that has weakened the influence of large business representatives, were viewed positively. Experts also observed an intensification of anti-corruption investigations by the NABU and SAPO, which over the past two years have initiated numerous cases against former MPs, the ex-Minister of Agrarian Policy, the ex-head of the SPFU, the SJA, and other top officials.

However, the report does not yet mention the principle of equality before the law for officials—a gap that reflects the general corruption within the law enforcement and judicial systems. Researchers note that, with winning the war as the top priority, anti-corruption efforts have taken a secondary role, and limited access to public data continues to pose significant corruption risks.

A report by Freedom House experts highlights the success of anti-corruption institutions in exposing and legally evaluating corruption in defense procurement (with the defense procurement legislation updated in early 2023). Also, human rights activists noted the reinstatement of mandatory electronic declarations for officials and the postponement of launching the register of oligarchs following comments from the Venice Commission. At the same time, Freedom House warns that certain corrupt officials may attempt to sabotage the state Anti-Corruption Program, which was adopted in March 2023.

Despite changes within the margin of error, a systemic negative trend is emerging in the study's results. According to experts, Ukraine's performance declined in five of the eight studies.

Where should Ukraine look for ways to improve its CPI performance?

The fact that our success in combating corruption is primarily a result of implementing international commitments and European Commission recommendations once again confirms that our country’s European integration is inextricably linked to the fight against corruption.

Ukraine needs to develop ambitious and comprehensive roadmaps for joining the European Union. This year, negotiations with the EU may begin with the first and most complex cluster, “Fundamentals”, which includes Negotiation Section 23 on Justice and Fundamental Rights—covering the fight against corruption. However, for Ukraine, the anti-corruption component will be integrated into every negotiation cluster with EU countries, spanning from agriculture, environment, and social policy to customs, transport, and energy.

Therefore, the newly developed screening report, along with the European Commission’s enlargement reports—which include numerous European integration requirements—should serve as valuable sources of guidance for improving the corruption situation. They could be the key to Ukraine’s breakthrough in the Index.

Additionally, many reforms are detailed in other documents. For example, the roadmap for the restoration in the Ukraine Facility Plan outlines requirements that must be met to secure monetary assistance from the EU. It is also worth mentioning the measures indicated in the IMF Extended Fund Facility. The implementation of these recommendations ensures the financial and macroeconomic stability of Ukraine and continues to play an important role for us.

But most importantly, the authorities should view the implementation of these requirements as a marathon to strengthen Ukraine—not as a short sprint aimed at securing funds, no matter how high a priority closing budget gaps may be. Simply ticking boxes on reforms will not yield strategic results; we must commit to playing the long game.

If we succeed, Ukraine may be able to demonstrate an effective fight against corruption, paving the way for genuine EU membership by 2029—a scenario predicted by the EU Enlargement Commissioner regarding Ukraine’s accession prospects.

The authorities should view the implementation of these requirements as a marathon to strengthen Ukraine—not as a short sprint aimed at securing funds, no matter how high a priority closing budget gaps may be. Simply ticking boxes on reforms will not yield strategic results; we must commit to playing the long game.