Authors: Pavlo Demchuk, Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine,

Andrii Tkachuk, HACC Case Monitoring Lawyer at Transparency International Ukraine.

After the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians waited for news about the confiscation of the foreign property of traitors and corrupt officials. However, like after the Revolution of Dignity, the Ukrainian budget was not filled under this item of income.

What prevents the Ukrainian law enforcement system from effectively confiscating the property of corrupt officials and traitors in Europe and the world? Find out how this process can be arranged in the opinion of Transparency International Ukraine’s experts.

The confiscation of criminal assets became a topic of discussion after the Revolution of Dignity in the context of property embezzled by Yanukovych and his entourage. Now it is being discussed in the context of the assets of Russians. It would also be useful to effectively confiscate the property of convicted Ukrainians who keep their assets abroad.

The primary reason for writing this article was the fact that quite often the assets obtained through the commission of crimes are withdrawn abroad. This is done to freely use such property without the threat of confiscation in case of criminal prosecution.

Law enforcement agencies report on seizures of property abroad on a relatively regular basis. For example, there is information that in August 2023, USD 113 mln was seized on the accounts of Kostiantyn Zhevaho in Switzerland. In August 2023, the sanctioned Russian oligarch Mikhail Shelkov was served with a suspicion notice of evading taxes, fees (mandatory payments), and legalization (laundering) of property obtained by criminal means.

These and many other facts indicate that work is underway to return stolen assets to Ukraine, but it has been a long time since we heard about any high-profile cases where seized assets would be confiscated abroad and returned to Ukraine. There are a number of reasons for this.

Therefore, in order to understand the conceptual issues that may impede the effective use of asset recovery tools in criminal proceedings, we decided to consult statistical data, interview government officials, and analyze regulations at the national and international levels.

The primary reason for writing this article was the fact that quite often the assets obtained through the commission of crimes are withdrawn abroad. This is done to freely use such property without the threat of confiscation in case of criminal prosecution.

How much property was confiscated abroad as part of the enforcement of court sentences?

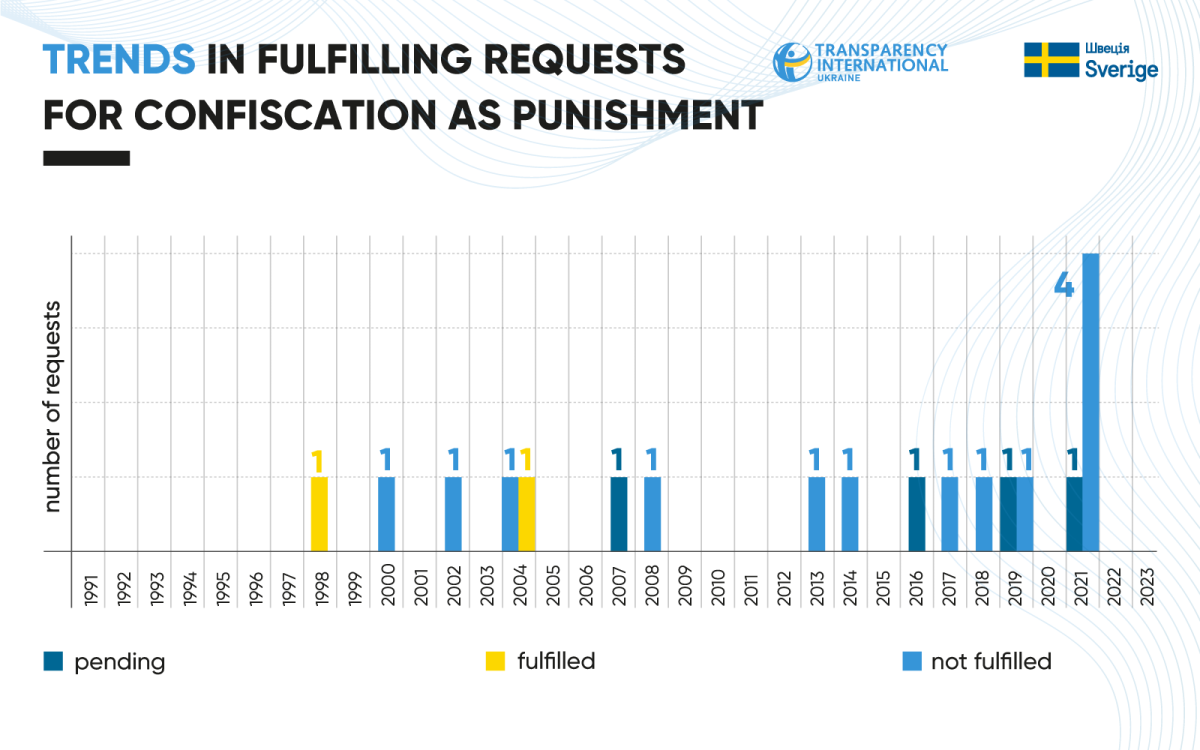

According to the Ministry of Justice, since the restoration of Ukraine’s independence and until October 2023, domestic courts have sent only 19 requests to enforce punishment in the form of confiscation of property abroad. Of these, 2 have been fulfilled, 13 have not been fulfilled, and 4 are pending.

Compared to the statistics of court decisions on confiscation of property in general, in the last 5 years alone, more than 6,500 verdicts were delivered, which provided for punishment in the form of confiscation of property. During this time, 8 of them were sent for enforcement by foreign competent authorities. That is, only 1 out of almost 1,000 verdicts concerns property located abroad.

Of course, it should be considered that not every convict owns property abroad. But, for example, in the 4-year practice of the HACC, there was not a single request to enforce a verdict abroad. Although the NABU reports that as of June 30, 2023, 1,501 requests for international legal aid were sent, and 1,033 of them were fulfilled. Some of these requests concerned the seizure of property.

For its part, the National Police of Ukraine reports that in 2020, the amount of the property seized abroad was UAH 757,307,843. In 2022 alone, the ARMA found UAH 145 mln abroad (in UAH equivalent as of December 31, 2022), as well as 422 real estate objects and 304 vehicles. In the future, this property should be seized and, ultimately, it could be confiscated.

This indicates that the property abroad, which is involved in criminal proceedings, does exist, but it has not been confiscated yet.

The systematic and static nature of the problem is also confirmed by the number of requests sent for confiscation of assets under verdicts. It can be seen from these data that such requests are almost evenly distributed over the years, and therefore, for 32 years, lttle attention has been paid to this problem, and no work has been done on its real solution. It should be noted that here we focus on information as of October 2023.

All this demonstrates the issues that exist in the field of asset recovery. Roughly, they can be divided into:

- regulatory. These issues include shortcomings in the regulation of the application of property confiscation, the process of sending requests to enforce this punishment abroad, as well as international treaties to which Ukraine is a party regarding the enforcement of sentences;

- organizational. These issues concern the practice of incriminating persons with crimes that cannot be effectively prosecuted abroad, the process of criminal prosecution in absentia, that is, in the absence of the accused, the shortcomings of asset tracing, and the use of mechanisms of joint investigative teams, as well as asset recovery agreements.

It is these issues, as well as causes and consequences of these issues, that we cover in our material.

Of course, it should be considered that not every convict owns property abroad. But, for example, in the 4-year practice of the HACC, there was not a single request to enforce a verdict abroad.

Confiscation of all property is a relic of the Soviet era

The statistics indicates that requests to enforce confiscations of property abroad in the last 32 years have been sent extremely rarely. But even if such requests are directed more often, the probability of their successful enforcement will remain very low. After all, a significant part of the refusals to enforce the confiscation of property was justified by the fact that the criminal codes of other states very often do not provide for the compulsory alienation of assets in the form available in Ukraine. In addition, in general, international treaties are mainly focused on the enforcement of decisions on the confiscation of criminal assets, rather than all property.

The fact is that the fundamental conventions defining the rules for the international confiscation of assets refer to confiscation as a punishment and as a measure (special confiscation). At the same time, the CoE Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime determines that in any case the confiscated property must have signs of criminal origin. The same is found in the UN Convention against Corruption, the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, and others.

Although the European Convention on the International Validity of Criminal Judgments provides for the possibility of enforcing confiscation sentences on the basis of a court verdict, it does not specify a mandatory requirement regarding the criminality of the nature of property. Nevertheless, this Convention has a safeguard that makes it impossible to confiscate the amount of assets that is not provided for such crimes by the legislation of the state in which such confiscation is requested.

Modern practice of most foreign countries (Lithuania, China, the Netherlands, and many others) suggests that property can be confiscated in criminal cases when it is of a criminal nature. That is, such assets were directly or indirectly related to the commission of a crime, and the investigation provided relevant evidence to confirm this.

The Ukrainian legal system declares that the confiscation of property occurs without any proof of its criminal origin, and the property of such origin is subject to special confiscation — a measure of a criminal law nature.

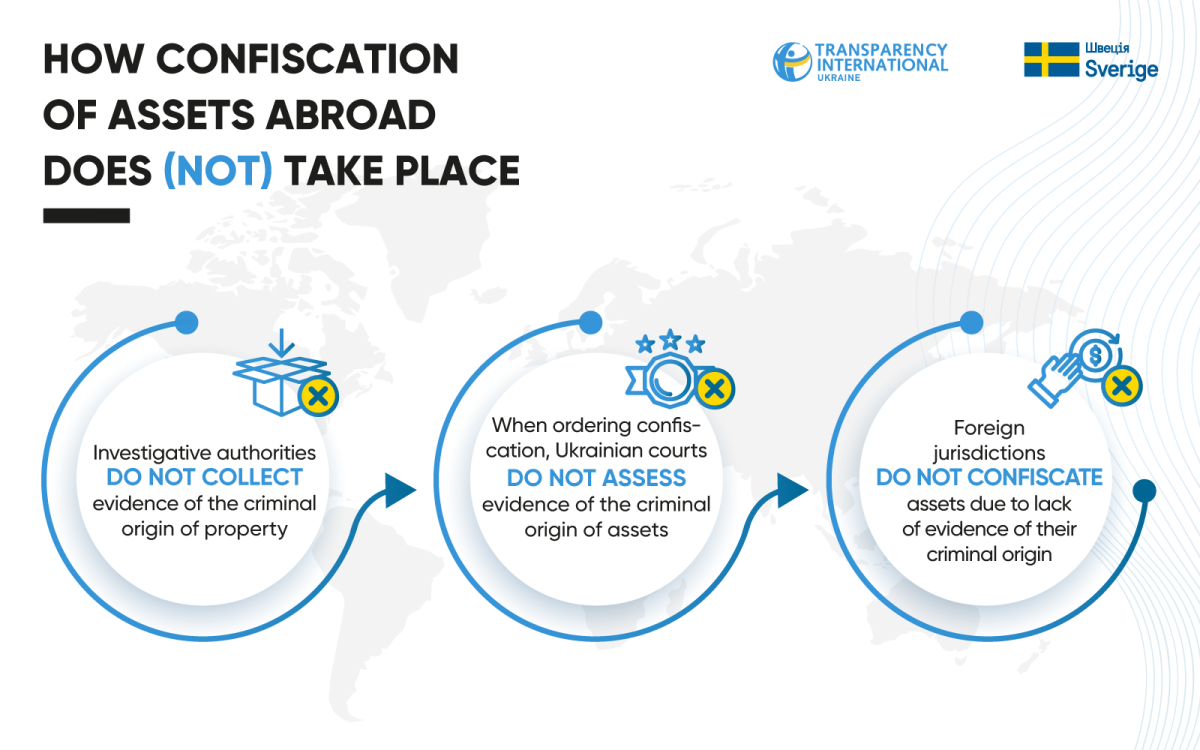

Therefore, in our case, the process is as follows:

- the investigating authorities, when searching for and initiating the seizure of property, do not prove its criminal nature;

- Ukrainian courts, when imposing confiscation as a punishment, do not evaluate the evidence to support this;

- foreign jurisdictions do not enforce this punishment because they need strong and court-confirmed evidence of the criminal nature of the property.

It should be noted that the draft criminal Code, which is now widely discussed in the professional community, eliminates this problem. It determines that only property or income from it that was in any way used to commit a criminal offense or income from such property can be confiscated.

A more attractive tool for use abroad is special confiscation. However, as the Ministry of Justice replied to our request, in the 10 years of the existence of special confiscation abroad, not a single request for its implementation was sent.

Special confiscation is understandable for foreign states, which is undoubtedly its advantage. The approach to confiscation of means of crime and the proceeds from its commission is the most acceptable among the world community and is enshrined at the legislative level in a number of foreign jurisdictions. However, the application of special confiscation is more complicated than the usual recovery of all property owned by a person into the national income because for this it is necessary to prove the connection between assets and a criminal offense.

In this context, attention can also be drawn to the progressive provision of Article 100, part 9, clause 6-1 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine, which, unfortunately, is not effectively used. This is a domestic analogue of extended confiscation, when the court has the opportunity to confiscate the property of a convict (or related persons) for committing a corruption crime, legalization (laundering) of proceeds from crime if it is not established in the court that such property was acquired legally. In other words, there is a presumption of unlawful acquisition of such property.

However, this provision contradicts the grounds for special confiscation defined in Articles 96-1 and 96-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which creates a conflict that does not allow its effective application.

A significant part of the refusals to enforce the confiscation of property was justified by the fact that the criminal codes of other states very often do not provide for the compulsory alienation of assets in the form available in Ukraine. In addition, in general, international treaties are mainly focused on the enforcement of decisions on the confiscation of criminal assets, rather than all property.

What is wrong with sending requests to enforce property confiscations?

In general, to conduct confiscation abroad, the court must draw up an appropriate request, translate it into the language of the country to which they want to apply, and send it to the Ministry of Justice for verification of compliance with the requirements of the special Guide.

If the requirements specified in the Guide are not met, the Ministry of Justice may return the request to the court with recommendations for correction or with an explanation of why such a request cannot be fulfilled. Currently, the Ministry of Justice has not returned any request for confiscation of property under a verdict to the court for the entire period of Ukraine’s independence. This can be explained not by the high level of quality of requests, but by their small number.

However, there are cases when the courts are mistaken in the grounds for sending a request. For example, the Hlybotskyi District Court of Chernivtsi Oblast, by its verdict of January 30, 2012, convicted an Italian for carrying and finishing an attempt to smuggle a cold weapon — a knife. The court prepared a request to Italy to imprison the convict, and in this request referred to the European Convention on the International Validity of Criminal Court Judgements of 1970. However, Italy was not a party to it, so the request was not fulfilled.

When sending requests for international legal aid, it should also be taken into account that their consideration can take a long time — from months to years. This is a very serious obstacle that hinders the process of returning criminal assets to Ukraine.

Of the four requests that are currently being considered by foreign colleagues, one is being fulfilled for more than a year, another one for more than 6 years, and one — more than 15 years.

It is impossible to accelerate this process by changes in national legislation, but the Ukrainian authorities are able to create a legislative and organizational basis for monitoring the status of consideration and implementation of such requests. Now this direction has intensified due to the approval by the Ukrainian government of the Asset Recovery Strategy for 2023-2025. We hope that this will allow us to find out about new and still unidentified problems, as well as offer effective solutions to them.

In addition, draft law No.8038, concerning amendments to the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine and other legislative acts of Ukraine regarding international cooperation during criminal proceedings, was under consideration by the Parliament. But the specialized committee returned it for revision.

This document somewhat detailed the process of international enforcement of court decisions. For example, it established the terms within which court decisions should be sent abroad, if the verdict provided for confiscation or special confiscation. It also has separate provisions relating to the recognition and enforcement of decisions of foreign courts on the territory of Ukraine. For example, allowing national courts to decide on the transfer of confiscated property, its monetary equivalent, or part thereof to victims.

The said draft law generally regulates the process of considering a request for the distribution or return of confiscated property. For example, such provisions are especially relevant given that at the end of September, a court in Serbia sentenced former SSU General Naumov to a year in prison for money laundering. During the inspection of his car, money and diamonds were found, which, according to the police, originated from criminal activity. Therefore, it would be appropriate to have provisions in national legislation regulating the powers of criminal justice bodies in the process of asset recovery.

One of these tools is international agreements on the distribution and recovery of assets to Ukraine. For example, the law on the ARMA mentions that the Agency may participate in the preparation of drafts of such agreements.Moreover, Art. 568 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine states that the court may decide to confiscate property if it is provided for by international treaties of Ukraine regulating the distribution of confiscated property or its monetary equivalent. However, the current legislation does not contain information on what exactly such international treaties should regulate, as well as the grounds for their possible conclusion. This may explain why law enforcement officers do not apply this practice.

Despite this, it is worth noting the positive work of the Department of the Ministry of Justice, responsible for sending requests in the field of international enforcement of decisions. This department advises the courts on the preparation of requests, conducts special training for judges and court officials, and it also appealed to the Supreme Court on the generalization of the practice of international enforcement of sentences.

It is impossible to accelerate this process by changes in national legislation, but the Ukrainian authorities are able to create a legislative and organizational basis for monitoring the status of consideration and implementation of such requests.

Qualitative and quantitative international agreements in the field of confiscation enforcement

Even if the request is drawn up in a quality manner, this does not guarantee the enforcement of the sentence due to the specifics of international agreements with some states. Despite the fact that Ukraine is an active player in the international arena, it still does not have well-established international relations with all states.

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, not all states are parties to the same conventions on the enforcement of confiscation abroad as Ukraine. Secondly, there are a number of states with which Ukraine has broken off relations or has not established them at all. Thirdly, Ukrainian bilateral agreements do not single out confiscation as a separate area of legal aid.

Currently, Ukraine is a party to more than 15 multilateral conventions that provide for mutual legal assistance within several international intergovernmental organizations, and has 26 bilateral treaties with different states on multilateral mutual legal assistance in criminal matters (with the exception of certain extradition and extradition treaties). This seems to be a significant figure, but, for example, Great Britain has as many as 42 similar bilateral agreements. And the more such transactions the better.

However, not only the high number of bilateral agreements can provide Ukraine with effective channels for international cooperation in asset recovery. The issue of their quality plays an equally important role, especially in the absence of special provisions in each of them or at least mentions of confiscation.

Here it is worth mentioning the problem of poor quality of developing bilateral international regulatory acts concluded by Ukraine. The lack of initiatives on our part to amend already concluded agreements to improve the efficiency of their use is another problem.

Technological and civilizational progress allows criminals to better withdraw and disguise assets abroad. Therefore, the establishment of new and improvement of old international bilateral mechanisms of international legal assistance will greatly simplify the enforcement of confiscations by foreign jurisdictions.

Persons involved in criminal proceedings deliberately use those states that do not monitor compliance with financial legislation and remain nihilists in international cooperation in a certain way. For example, the “grey list” of countries under enhanced FATF monitoring includes Albania, Croatia, the Philippines, Syria, the UAE, and Turkey. However, Ukraine has agreements on cooperation in criminal matters only with the UAE and Syria, although, obviously, one should not expect compliance with the agreements with the latter.

This is what criminals can take advantage of, who, in addition to their own hiding, bring assets there so that our state bodies cannot get to them. Therefore, drawing up and sending such requests by Ukrainian courts, even if available, will be ineffective from the very beginning.

Here it is worth mentioning the problem of poor quality of developing bilateral international regulatory acts concluded by Ukraine. The lack of initiatives on our part to amend already concluded agreements to improve the efficiency of their use is another problem.

What and how should be changed in the legislation so that confiscation abroad works?

Based on the above, we provide 5 recommendations that could facilitate the confiscation of criminal assets in other countries.

- Bring the confiscation of property in line with generally accepted international standards. That means confiscating not all the property of a person, but only that which was used in the process of committing a crime or obtained as a result of it.

- Provide for “extended” confiscation of property in the Criminal Code of Ukraine. This will eliminate the conflict between substantive and procedural law.

- Settle the issue of sending sentences for confiscation of property abroad for enforcement by specifying the terms of such sending, as well as to grant the courts certain powers of the court related to international confiscation. This will allow avoiding delays in the enforcement of the sentence abroad, and will also help solve a number of problems associated with the use of international legal assistance tools in criminal proceedings.

- Initiate the conclusion of new and improvement of existing bilateral agreements on material legal assistance in criminal cases in terms of confiscation of criminal assets. Ukraine should contribute to improving the quality and increasing the number of international bilateral agreements in the field of providing material legal assistance to reduce the space for criminals to hide illegally acquired or used assets.

- Change approaches to proving the criminal origin of property. If this is not necessary for the application of simple confiscation, then it is appropriate for extended or special confiscation. As we have already noted, to enforce confiscation of property abroad, it is necessary to establish a link between the crime and the assets.

However, the irregularity of Ukrainian legislation on the confiscation of criminal assets abroad is only one area of problems in this matter. There are many difficulties in the actual organization and implementation of such processes by the state bodies.

This publication was prepared by Transparency International Ukraine with the financial support of Sweden.