Authors: Pavlo Demchuk, Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine,

Andrii Tkachuk, HACC Case Monitoring Lawyer at Transparency International Ukraine.

Confiscation of criminal assets abroad is a very complex process. However, a year and a half into the full-scale invasion, we see that the problems that our legal and law enforcement systems encounter when initiating such procedures are not only based on the shortcomings of Ukrainian legislation.

In the first part of our study, we have covered the issues at the legislative level that make it difficult to confiscate assets abroad effectively. So, now let us consider bugs in the practical sphere.

“Conventional” and political: in what crimes is confiscation of property abroad possible?

When prosecuting persons in respect of whom it will be necessary to send requests abroad, it should be considered that they are to be prosecuted for crimes recognized by the world community as “conventional.” These include terrorist financing, corruption, drug trafficking, etc.

After all, there may be problems with a certain category of criminal offenses if they are classified as political crimes. For example, the European Convention on the International Validity of Criminal Judgments states that the enforcement of a sentence may be refused when the requested State considers that the crime for which the sentence was passed is of a political nature or is purely military.

In general, the concept of refusal because of political crimes is widely developed and discussed. Its essence lies in the fact that states, as a general rule, do not help each other in prosecuting a political crime. Political crimes usually include treason, espionage, and calls for rebellion.

Currently, Ukraine is a party to 6 multilateral conventions fundamental in this context:

- European Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime, 1990;

- Council of Europe Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime and on the Financing of Terrorism, 2005;

- UN Convention against Corruption, 2003;

- Criminal Law Convention on Corruption, 1999;

- United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, 2000;

- United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988.

If there is a choice, law enforcement agencies should charge with “conventional” crimes. All States that are parties to such conventions have obligations both to criminalize these acts and to help combat them.

A positive example is the recent incrimination of the Russian oligarch Mikhail Shelkov with the legalization (laundering) of income. While the first suspicion notice concerned the financing of actions committed with the aim of forcibly changing or overthrowing the constitutional order (Art. 110-2, part 3 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine). Such an addition to the qualification of the crime will allow the effective enforcement of punishment abroad.

In addition, attention should be paid to the requirement of “double criminalization.” As a general rule, punishment can be enforced in another state when the same actions are punishable under its legislation. In 2004, this became the basis for the refusal to enforce the verdict of the Slavutych City Court of Kyiv Oblast on the confiscation of funds of a person convicted of illegally opening a foreign currency account outside Ukraine (former Article 208 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) because it was not a crime in the state addressed.

Therefore, the most likely way to obtain a positive result of the confiscation abroad is to bring the perpetrators to justice for the above-mentioned conventional crimes.

If there is a choice, law enforcement agencies should charge with "conventional" crimes. All States that are parties to such conventions have obligations both to criminalize these acts and to help combat them.

Conviction in absentia may interfere with asset confiscation

In case a person is hiding from the court, the legislator provided the possibility of conducting special judicial proceedings against them (in absentia) in the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine, that is, effectively considering the case in court in the absence of the accused. This should allow the effective enforcement of property punishments, as well as worsening the lives of fugitive criminals.

Such a novelty was introduced after the events of 2014, when the Rada amended the CPC of Ukraine in response to the fact that a significant part of potential suspects and accused began hiding in the temporarily uncontrolled territories of Ukraine and in Russia. Currently, in absentia is a common practice in criminal proceedings, but it has noticeable and invisible drawbacks.

For example, the HACC is currently considering the “gas case” of Oleksandr Onyshchenko. In January 2020, the court granted permission to consider this proceeding in the absence of the accused. In December 2021, judges seized the German equestrian facility Gut Einhaus within special confiscation. If Onyshchenko is found guilty of the actions he is charged with, which we will learn in December, then in order to enforce the verdict in terms of special confiscation, it will be necessary to consider German legislation on the conditions for the legality of a conviction in absentia. After all, the enforcement of the sentence should not contradict the principles of the legal system of the state that is asked to enforce the sentence.

In addition, the European Convention on the International Validity of Criminal Judgments stipulates that in order to enforce a sentence deliverd in the absence of the accused, it is necessary that the convicted person be personally informed of such a court decision. That is, sentences delivered in absentia will not be enforced by any foreign jurisdiction unless the convicted person is informed of it personally.

According to Art. 323 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine, the accused is informed about the trial by sending a summons to the last known place of their residence, published in the mass media of the national sphere of distribution (Government Courier) and on the official website of the court. Whether these measures are enough is a debatable issue.

For example, during the MH-17 case in The Hague, informing about the trial was conducted through the Russian authorities. It was also done through unofficial channels, for example, through the ruscist network VKontakte; letters in messengers; phone calls, after a voice examination was conducted. The judges also assessed whether the accused had published any information from which it could be established that they were aware of the trial.

The European Convention on the International Validity of Criminal Judgments stipulates that in order to enforce a sentence deliverd in the absence of the accused, it is necessary that the convicted person be personally informed of such a court decision. That is, sentences delivered in absentia will not be enforced by any foreign jurisdiction unless the convicted person is informed of it personally.

Searching for property abroad: mission (un)important?

Before collecting evidence that would confirm the possibility of applying special confiscation, it is necessary to search for the relevant property. In particular, for this purpose, the Asset Recovery and Management Agency was created; it is to search for assets that can be seized and confiscated at the request of the investigating authorities. This information becomes the basis for sending requests for seizure of property under the procedure of international legal assistance.

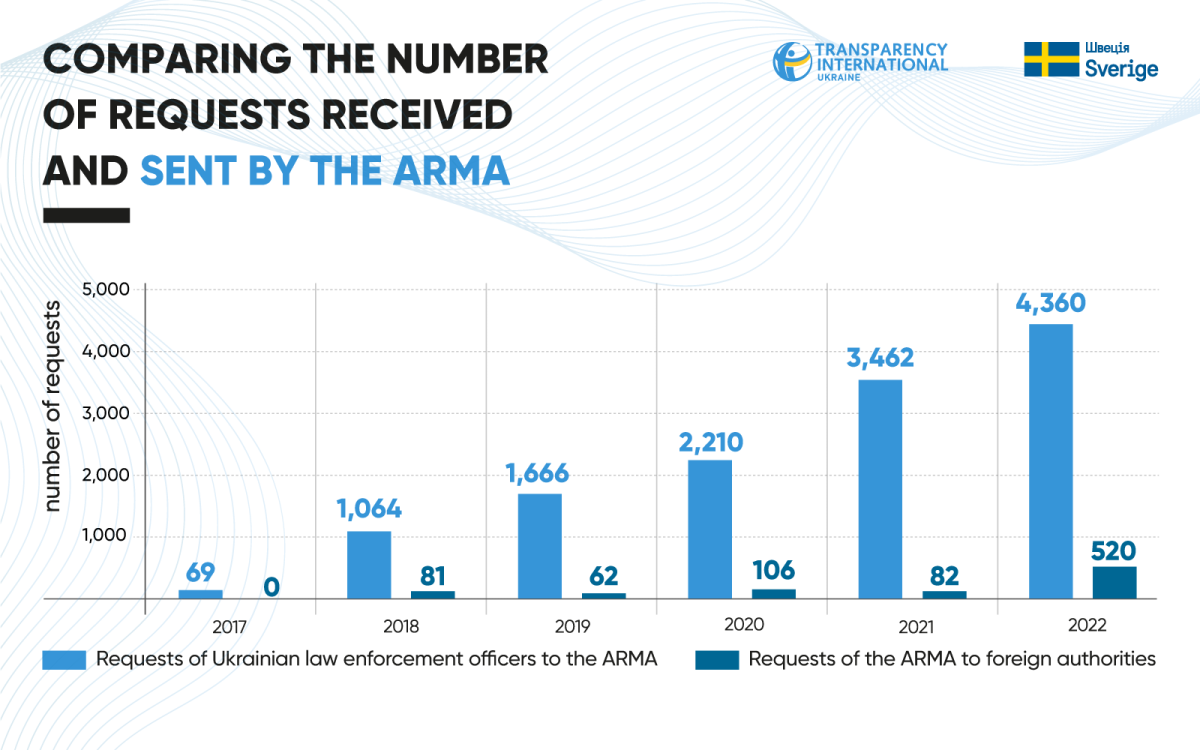

However, we can notice that the number of requests sent by the ARMA to foreign jurisdictions within the framework of cross-border information exchange remains low, especially if we consider the number of requests law enforcement officers send to the ARMA.

The ARMA cooperates with a number of international movements and organizations whose work is aimed at coordinating the exchange of information between different states on the movement and location of criminal assets, including global and regional networks for asset recovery StAR, CARIN, BAMIN, Interpol.

In total, for the period of 2017-2022, only 851 requests for asset tracing were sent to foreign competent authorities (almost two-thirds of them in 2022), while domestic law enforcement officers sent 12,861 requests to the Agency.

That is, the international search for assets increased after the full-scale invasion, but the volume of requests to foreign states for the described period is much less than the requests of Ukrainian law enforcement officers to search for property in Ukraine.

In part, such a significant difference between international and national tracing and asset recovery can be explained by the features of the current legal regulation. The interaction between the ARMA and law enforcement officers on how the asset tracing process is carried out is regulated by a special procedure. It stipulates that in order for the ARMA to begin searching for the assets of the defendant abroad, the investigator or prosecutor must provide evidence that this person has some kind of connection with a particular country. This effectively diminishes the search potential of the ARMA when it comes to assets located abroad. The investigator or prosecutor may not always have information about the connection of the person involved in the proceedings with a particular jurisdiction, while ARMA specialists have the knowledge and resources to carry out such a search.

At the same time, the search for assets abroad is only the first element in the process of their recovery. Subsequently, it is necessary to seize this property so that the defendant in the proceedings could not get rid of it. Although this is a common practice of law enforcement agencies, it does not indicate that these assets will eventually be confiscated. All because of the duration of hearing cases by Ukrainian courts.

There were cases when, before the end of the trial in Ukraine, seizures imposed abroad were lifted due to the fact that they were not extended on time, or the maximum term of encumbrance of such property expired.

In general, the seizure of property is an interference with the right of ownership, so its restriction should be justified, and the delay in the trial is a problem of the state, from which, according to international standards, an individual should not suffer. Moreover, some states, unlike Ukraine, determine the limited duration of seizure. Therefore, there were cases when it no longer made sense to send the decision on confiscation for enforcement abroad because the property was not seized, so it could be lost or collected by another jurisdiction.

Thus, in 2016, Latvia collected USD 50 mln belonging to Yanukovych’s entourage, and it was withdrawn to this country. The Latvian side then initiated criminal proceedings on these facts and first seized the amount, and then confiscated it into the income of its own budget. By the way, Latvian legislation allows this to be done even before the completion of the investigation. The then Prosecutor General of Latvia, in a comment to journalists, said that the Ukrainian side had not requested its recovery. Moreover, according to him, Ukrainian law enforcement officers were very passive in cooperation and did not provide relevant answers or completely ignored the requests of the Latvian side for legal assistance in this case.

Subsequently, Prosecutor General Yurii Lutsenko complained about the Latvian authorities that they had not waited for a decision in Ukraine. However, his comment and the whole situation only confirm that national legislation and authorities are incapable of properly implementing international cooperation when it comes to the recovery of criminal assets. One of the key reasons for this is the length of criminal proceedings.

Interestingly, indicators of the duration of criminal proceedings can be found only in the statistics of the High Anti-Corruption Court. According to these data, as of June 30, 2023, the average duration of hearing a criminal case by the HACC for all 4 years is 288.6 days per case. This statistics is common both for the consideration of materials by investigating judges and for the consideration of criminal proceedings on the merits. That is, the average duration of consideration of criminal proceedings on the merits (those that should end with a verdict) is even longer.

This is another systemic problem of criminal justice in the list of those that we have repeatedly talked about. It also prevents the recovery of assets from abroad.

The istuation is aggravated by the fact that national criminal procedural legislation does not clearly specify who is responsible for foreign asset seizure control, especially in those jurisdictions where property seizure is imposed for a fixed period. For example, in Slovenia, the seizure and confiscation of property is limited to a maximum duration of three months in pre-trial proceedings and six months in court proceedings. These measures may be extended, but not for longer than one or two years, respectively.

There were cases when, before the end of the trial in Ukraine, seizures imposed abroad were lifted due to the fact that they were not extended on time, or the maximum term of encumbrance of such property expired.

Joint investigative teams — a practice that must be strengthened

An international tool in the form of joint investigative teams can help synchronize asset confiscation efforts. In Ukraine, it is regulated by Art. 571 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine, which stipulates that such groups can be created to conduct a pre-trial investigation of crimes committed on the territories of several states, or if the interests of these states are violated.

Such investigative groups are formed by the Prosecutor General’s Office at the request of the investigative body of pre-trial investigation of Ukraine, the prosecutor, and the competent authorities of foreign states.

The NABU has successfully applied this tool in several cases. For example, in the investigation of corruption in Ukravtodor, as well as the scheme of embezzling the funds of the state enterprise Printing Plant Ukraine.

According to the investigation, in the Ukravtodor case, the ex-head of the agency committed incriminated crimes in Ukraine, and the unlawful benefit was transferred to the territory of the Republic of Poland. In the case of the Polygraph Combine, the NABU reported that the evidence received from Estonia allowed establishing all the details of the scheme of the crime and money laundering. As part of a joint investigation, Estonian law enforcement officers prosecuted four people for laundering funds stolen from the company.

Thus, both cases concerned an international element — either the place of the alleged crime was on the territory of another state, or foreign companies were used to facilitate the commission of the crime. Therefore, the use of the mechanism of joint investigative groups made it possible to quickly collect and legalize the evidence obtained in these cases, as well as not to waste time on long-term mechanisms of international legal assistance.

Currently, the case of bribery of the ex-head of Ukravtodor is under consideration in court, so we can track the court’s approach to assessing the evidence collected in this way.

The legal regulation of joint investigative groups is already being improved to enable effective documentation of crimes of Russian terror. MPs have registered a draft law No. 7330, which to some extent details Art. 571 of the Crimianl Procedural Court of Ukraine on the grounds for the formation and functioning of joint investigative groups and the admissibility of the evidence collected. However, the experts of the advisory group of the Council of Europe provided a rather critical opinion on this draft law.

The NABU has successfully applied this tool in several cases. For example, in the investigation of corruption in Ukravtodor, as well as the scheme of embezzling the funds of the state enterprise Printing Plant Ukraine.

What should be considered for the successful recovery of confiscated assets to Ukraine?

First of all, it must be remembered that the confiscation of criminal assets abroad is a time-consuming process that involves both the consolidation of efforts at the diplomatic level and the conduct of high-quality pre-trial investigation and trial. As we can see, both the legislation and the practice of applying confiscation require changes.

We have already written about the necessary legislative changes earlier. What needs to change at the organizational level?

- To consolidate the procedure and features of concluding and implementing agreements on the distribution of assets and agreements on joint investigative groups at the legislative level. Agreements on the distribution of confiscated assets and on joint investigation groups are provided for by a number of international conventions and represent convenient tools for interstate cooperation in criminal matters. That is why detailing the procedure for their conclusion and implementation at the legislative level will increase the practice of their use.

- To enhance the use of the asset distribution agreement tool, as well as the activities of joint investigative groups in this context. The experience of the NABU shows that these tools are used, but their use is very limited, so it is worth extending such practices to the activities of other law enforcement agencies.

- To select the right tools to bring the perpetrators to justice. Despite the rigidity of criminal law, law enforcement agencies have the discretion in which crimes to investigate and under which article to prosecute a person — the main thing is that this is based on the evidence obtained. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on “conventional” crimes; the enforcement of sentences for these crimes should entail fewer problems.

- To train investigators, prosecutors, and judges. This is equally important for understanding all asset recovery mechanisms and their use in specific cases. Recovery of assets is possible not only through their confiscation in criminal proceedings, but also through civil forfeiture, initiation of criminal proceedings in foreign countries, and provision of the necessary evidence in the framework of international cooperation. These possibilities are not always obvious, if only in the context of national legislation. Therefore, all available means should be used to improve the quality of national investigations and recover stolen assets to Ukraine.

***

All the problems of confiscation of criminal assets abroad mentioned by us are not new; both the authorities and the public are well aware of them. Even the European Commission in its report on the assessment of Ukraine’s progress drew attention to the importance of intensifying work on asset recovery.

Therefore, we hope that the Ukrainian authorities will make every effort to consider the identified problems both in the legislative framework and in the practice of its application. Of course, the correction of the shortcomings mentioned by us may take some time and, as we can see, a lot of time will be spent on the actual recovery of such property in the future. But without such actions, it is unlikely that criminal property will be used for the benefit of Ukrainians.

This publication was prepared by Transparency International Ukraine with the financial support of Sweden.