The ongoing Russian war of aggression against Ukraine is causing unspeakable human tragedy. In addition, it is destroying the country’s economy and essential infrastructure. Rebuilding this will be a crucial pre-requisite for a country-wide recovery, economically, socially and politically.

Unprecedented levels of funding to enable this reconstruction are currently being raised by the international community, including at the forthcoming Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland. It is estimated that at least 1 trillion USD will be needed, a sum likely to increase as the war wages on.

Many things have changed radically in Ukraine since February 24th, 2022. Corruption risks, unfortunately, have not. If corruption is allowed to go unchecked, Ukraine’s reconstruction would hand a massive victory for the subversive kleptocratic war that the Kremlin has been waging since Ukraine’s independence to undermine the country’s statehood. Therefore, effective anti-corruption systems are not “merely” important to fight corruption, but provide crucial defenses in the war against kleptocracy which is intimately linked to the military war.

This is not new to Ukraine, and the issue of corruption has always been prominent. The Corruption Perceptions Index shows that over the past ten years, Ukraine has been slowly, but steadily, improving. Ukraine is one of only 25 out of 180 countries that have improved in a statistically significant way in the past 10 years. The Association Agreement and the Visa Liberalization Action Plan with the EU, among other, and cooperation with other international partners has contributed significantly to this success. On the 23 of June this year all 27 member states of the European Union voted in favor of granting the candidate status to Ukraine which will also have a positive impact on the fight against corruption.

Yet, the existing anti-corruption defenses are not yet sufficiently robust to ensure reconstruction funds are spent with integrity, and this was also noted in the conditionality outlined by the European Commission. While it is unrealistic to expect that the country can progress all outstanding anti-corruption reforms while the war is still raging, some must be tackled right away. Together, these will enable anti-corruption fighters to unleash the fighting spirit that Ukrainians have become famous for.

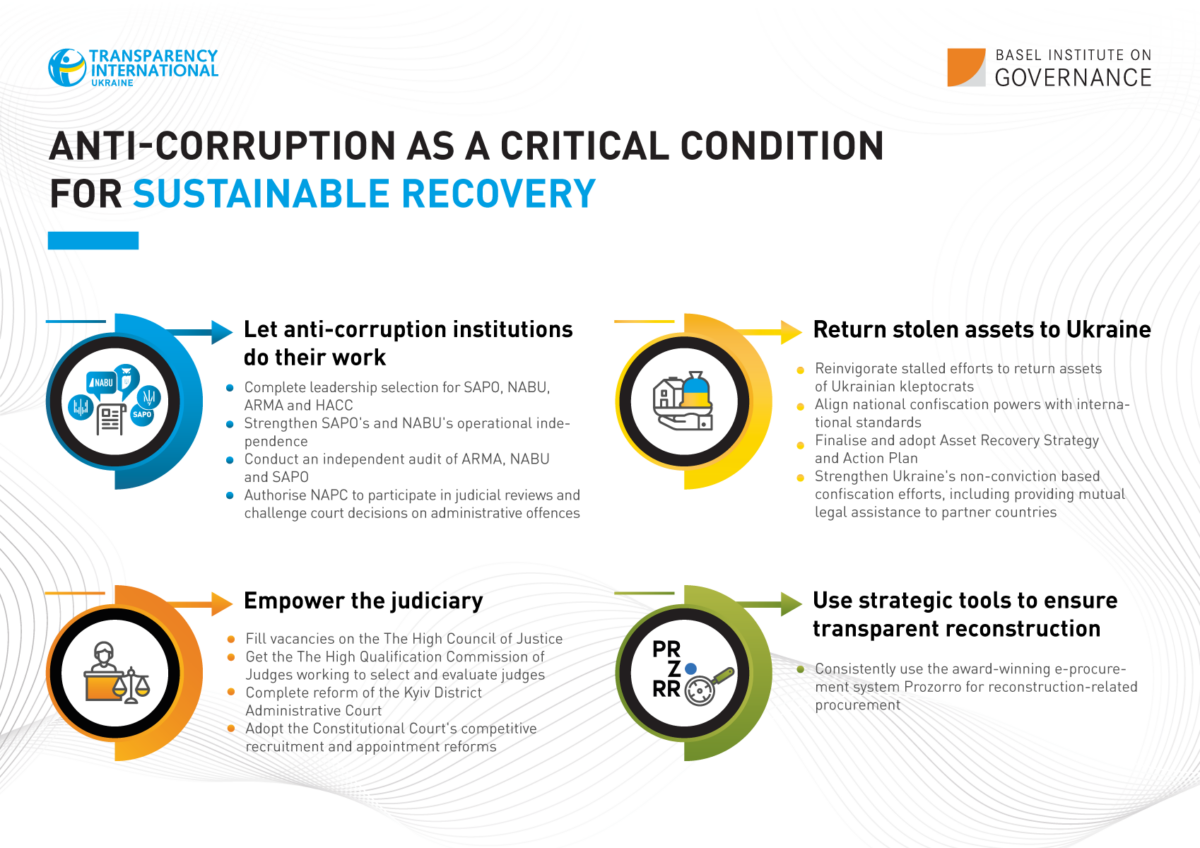

Let anti-corruption institutions do their work

Ukraine and its allies have spent the last decade building a diverse and impressive institutional infrastructure to fight corruption. However, political obstructionism has left it devoid of leadership.

The top positions at the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecution Office (SAPO), the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) and the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA), which investigate, prosecute, adjudicate corruption cases and manage returned assets, respectively, are all vacant. In some cases, all that’s necessary is to finalize a stalled selection process (SAPO). In others (NABU, ARMA and HACC), independent and fair competitions will have to be completed. This is a weakness for Ukraine, especially if combined with challenges in the institutions’ independence and enabling legislative framework. Caretaker leaders in some cases lack the authority to fully fulfill their functions. This also affects efforts to pursue those who will seek to illegally profit from the reconstruction process.

To ensure Ukraine’s anti-corruption institutions can do their work, it is imperative that:

- Leadership selection process for SAPO is swiftly completed.

- Selection and appointment processes of the heads for NABU, ARMA and HACC are started swiftly and conducted transparently and competitively.

- SAPO’s operational independence needs to be strengthened, its leadership authority expanded, and risks of unjustified interference minimized.

- The NABU law needs to be amended, at a minimum to solidify its jurisdiction in high profile cases and establish a specialized forensic investigations unit; its wiretapping authority needs to be swiftly confirmed.

- An independent, comprehensive performance audit of ARMA, NABU and SAPO should be conducted to identify a clear path forward to ensure it lives up to its full potential.

- The National Anti-Corruption Prevention Committee (NAPC) must be authorized to participate in judicial reviews and challenge court decisions on administrative offenses.

Use strategic tools to ensure transparent reconstruction

Complementing this work of anti-corruption institutions is the award-winning e-procurement system Prozorro, one of Ukraine’s key transparency and accountability achievements.

Support for it among the government had waned before the war. Now is the time to make use of strategic assets, consistently using Prozorro for reconstruction-related procurement.

Empower the judiciary

The judiciary has long been the Achilles heel of Ukrainian anti-corruption efforts, famously destroying key achievements in 2020 and causing a constitutional justice crisis that was barely resolved in 2021. Unblocking the stalled judicial reform process is a crucial pre-requisite for the recovery, including in view of the numerous inevitable contractual disputes that will arise from the reconstruction efforts.

Key priorities include:

- The High Council of Justice (HCJ), responsible for the judicial appointment and integrity oversight of crucial courts, needs to be given legitimacy by filling the large number (15 out of 21) of current vacancies.

- The High Qualification Commission of Judges (HQCJ), responsible for the selection and qualification evaluation of judges, needs to start working as soon as possible.

- As soon as hostilities end, the stalled reform of the obstructionist Kyiv District Administrative Court needs to be speedily completed; failing that there is a significant risk that this crucial court will undermine any reconstruction-related litigation.

- The long-suffering Constitutional Court’s competitive recruitment and appointment reforms need to be adopted to remove doubts about its legitimacy and integrity.

Bring back Ukraine’s stolen assets

The matter of recovering proceeds of crime has never been higher on the political agenda in Ukraine than now in the context of planning for reconstruction efforts.

The focus is on the recovery of Russian assets frozen under war related sanctions, and the moral imperative for this is quite compelling. However, Switzerland’s recently commenced innovative confiscation proceedings against assets ascribed to Yanukovich ally Yuryi Ivanyushchenko remind us that, in addition to the Russian assets, there are significant outstanding Ukrainian kleptocratic resources that await repatriation and where insufficient progress has been made since 2014. Unlike the Russian money, these do not require new legal mechanisms, only follow-through and the application of the right legal and international cooperation tools. The moral case to return these assets is at least as strong.

To recover proceeds of crime committed in Ukraine in order to contribute to reconstruction, we recommend that:

- Authorities re-invigorate stalled efforts to return assets of Ukrainian Kleptocrats by completing domestic investigations and bringing the cases to Court so that confiscation orders can be enforced in foreign jurisdictions.

- Ascertain that confiscation provisions used in international cases are enforceable in foreign jurisdictions.

- Finalise and adopt the Asset Recovery Strategy and Action Plan, following a review to update the documents in light of the post-war risks and priorities.

In relation to Russian funds outside of Ukraine: Turning assets frozen in foreign jurisdictions under war related sanctions into confiscations will be a particularly challenging task, and it is hotly debated in the legal community. Given the top-notch legal defense that the sanctioned individuals can afford, the international community would be well-served to refrain from political rhetoric and design a system that is guided by due process, the rule of law and respect of national and international human rights laws and treaties. Anything less would undermine confiscation efforts before they even start.

The greatest weakness of laws considered or adopted in Ukraine for the purpose of confiscating assets frozen under war related sanctions is insufficient legal recourse. Without improvements, these seizures risk being successfully challenged in the European Court of Human Rights. Ukraine also needs to ensure that its own legal tools are suitable for potential confiscation efforts undertaken by partner countries. To this end, Ukraine should:

- Strengthen Ukraine’s own non-conviction based confiscation efforts, including providing mutual legal assistance to partner countries who are pursuing this legal route.

- Align confiscation powers provided for in Ukrainian laws with international standards to ensure that they are acceptable to western courts. This includes, first and foremost, augmenting the legal redress clauses of the two war-time laws № 2116-IX and № 7194.

It is clear what needs to be done. Most of us don’t fight on the front, but sit safely in offices. The least we can do is honor heroic sacrifice by not allowing the reconstruction efforts to be tainted with corruption.

As a bonus: nothing would undermine the Kleptocratic Kremlin more than a Ukraine that is able to rise from the ashes with integrity.