Earlier, we studied how Ukrainian confiscations are enforced abroad. It is time to find out how they are enforced in Ukraine.

How do judges confiscate property from persons involved in high-profile corruption cases?

Many corruption offenses are mercenary, that is, the defendants seek to benefit from their positions. Because of this, the law provides for property punishment in the form of confiscation. It also indicates the possibility of special confiscation — as a measure that collects the proceeds from an offense and the property used in its commission.

We explained the difference between these measures in another article. In short, ordinary confiscation covers the legitimate property of the convicted person, while special confiscation is about criminal proceeds and funds.

The HACC has the right to confiscate property only under a third of the articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine under its jurisdiction. Mostly, such a punishment is mandatory, that is, judges cannot decide whose property to confiscate and whose not to. Only in Articles 365-2 (Abuse of power by persons providing public services) and 369 (Proposal, promise or providing an improper advantage to an official) of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, this issue is at the discretion of the court.

In the four years of its operation, the High Anti-Corruption Court delivered more than 150 verdicts, and 48 of them contained punishment in the form of confiscation of property (this is considering classified verdicts). As of December 31, 2023, 61 persons were sentenced to such a punishment, and this trend with the imposition of this type of additional punishment is only growing, including due to a gradual increase in the number of sentences.

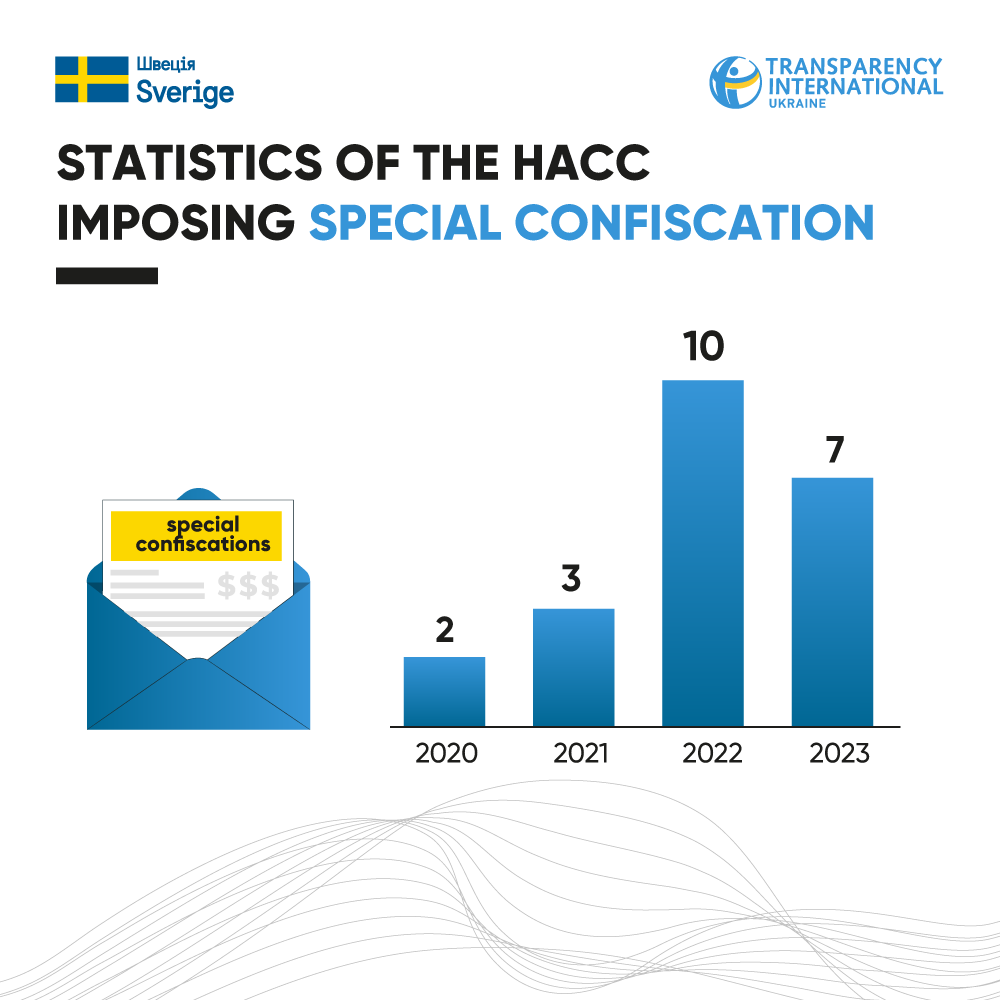

The HACC may apply special confiscation in the event of a commission of the offenses under its jurisdiction, except for the crimes provided for in parts 1 and 3 of Art. 357 (Stealing, appropriation, or extortion of documents, stamps and seals, or acquiring them by fraud or abuse of office, or endangerment thereof) of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. However, the Anti-Corruption Court applied it in only 22 sentences (as of December 31, 2023), and this is significantly fewer than the number of confiscations of property as punishment.

Unlike confiscation-punishment, special confiscation is applied more than twice as rarely, and there is no tendency towards an increase in cases of its application. This can lead to negative consequences. Find out in the article why it is so.

In the four years of its operation, the High Anti-Corruption Court delivered more than 150 verdicts, and 48 of them contained punishment in the form of confiscation of property (this is considering classified verdicts).

Existential problem of property confiscation

The UN Convention against Corruption obliges states to apply confiscation only to assets that are of a criminal nature, that is, the proceeds of crime, as well as property that was used to commit these offenses. However, an analysis of national jurisprudence shows that confiscation as a punishment is used to some extent to deprive a person of the opportunity to enjoy improper advantage, for example, in situations where the prosecution did not try to prove the criminal nature of the property acquired by the convicted person. In this case, it is impossible to apply special confiscation, and the court can only apply confiscation of property as a punishment.

The confiscation of property as a form of punishment under Ukrainian law has long been criticized. This is a legacy of the Soviet regime, inherent in many countries of the former USSR.

For example, Latvia faced a similar problem. At one time, the ECHR stated in the decision of Markus v. Latvia that the Latvian national confiscation legislation was vague and unpredictable, it did not provide the necessary procedural guarantees and did not guarantee protection against arbitrariness. Therefore, there was a violation of Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the Convention.

That is, for a lawful confiscation of property, it is necessary to prove its connection with the offense — so that the accused clearly knows which asset is confiscated and on what grounds.

Some academics also criticize the Ukrainian model of property confiscation. Their arguments refer to inequality in financial situations, allegedly, a person who has assets to confiscate loses much more than one who has no assets to confiscate.

The latter point is also illustrated by the practice of enforcing HACC decisions. In some cases, the state executive service failed to enforce a decision on confiscation due to the lack of property of the convicted persons or the lack of access to property in the temporarily occupied territories.

This is exactly what happened in the case of a judge of the Sievierodonetsk City Court of Luhansk Oblast, who was convicted of receiving a bribe of USD 4,000 for adopting the “right” decision. The response of the enforcement service indicated that he did not have any movable and immovable property, and the funds were not enough even to cover court costs. In another case, the state managed to recover almost UAH 400,000 from the confiscation of the property of a convicted judge of the Mizhhiria District Court in Zakarpattia Oblast.

Another interesting example is when searching for the car of the director of the State Enterprise Hutianske Forestry, law enforcement officers found UAH 92,900 and USD 5,700 of cash. The prosecution did not try to prove its criminal nature, but by convicting this person for bribery of a detective, the court confiscated the money under the rules of confiscation as a punishment. In the same case, USD 100,000 as a bribe was specially confiscated.

There is also a problem with the application of confiscation when concluding agreements. Namely, if the court approves an agreement under which a person will be exempted from serving a sentence, then in accordance with Art. 77 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, the parties to the agreement cannot agree on the confiscation of property as an additional punishment.

This all points to the need to revise legislative approaches to the understanding and the scope of confiscation of property as a punishment. Convicted corrupt officials must compensate for losses, as well as lose the proceeds of crime, and these processes must take place lawfully, without the risks that the state will apply unlawful procedures.

For a lawful confiscation of property, it is necessary to prove its connection with the offense — so that the accused clearly knows which asset is confiscated and on what grounds.

How does the HACC decide which property to confiscate?

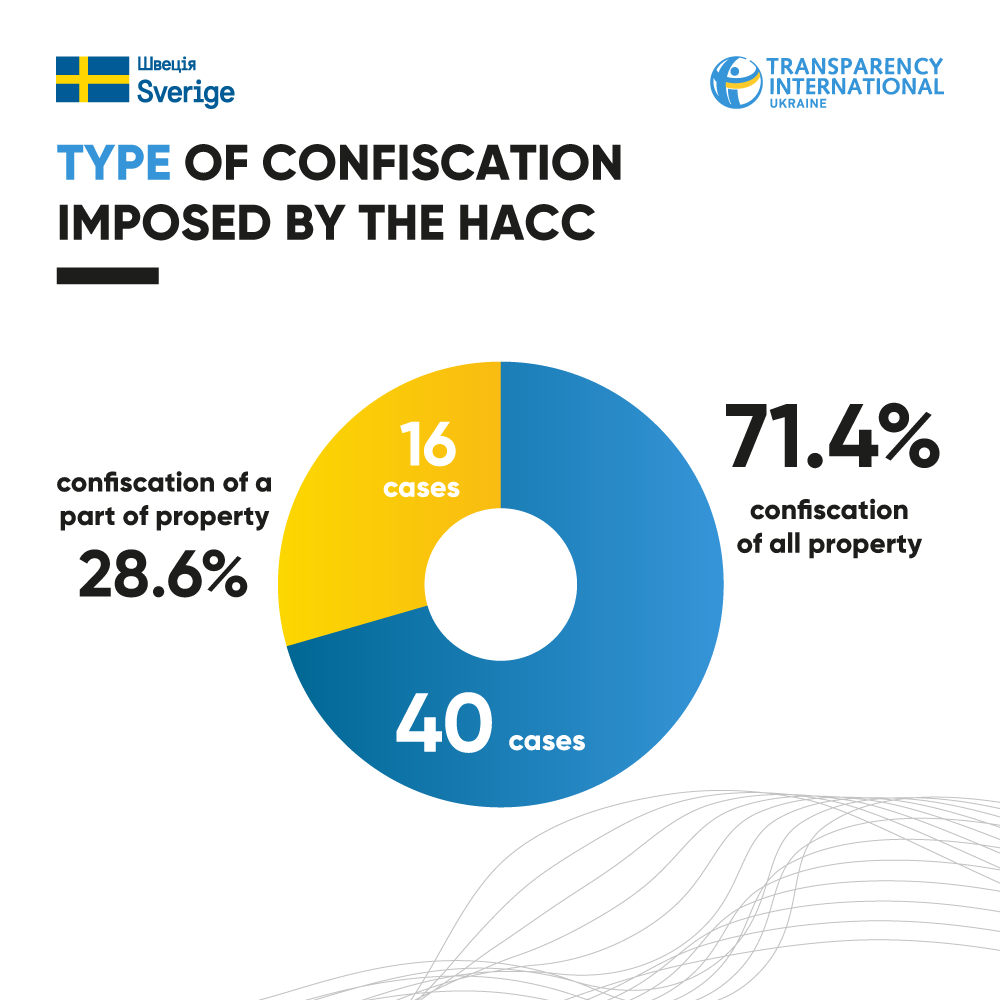

Most often, choosing between full or partial, the HACC prefers the confiscation of all property. We see this in the statistics: out of 44 publicly available verdicts of the court of first instance, in 40 cases, confiscation of all property was imposed on persons (71%) versus 16 cases of partial confiscation (29%).

The HACC takes different approaches to partial confiscation. It mainly takes place through a free transfer of half of the convicted person’s property to the state. We have identified 10 such cases. In 5 cases, the court confiscated specific items, such as cars, land plots, houses, etc. One case concerned the confiscation of all property except half of the apartment.

The legislation does not regulate how to decide whether to confiscate all the property of the convicted person or a part of it. Considering this, judges are guided by the general principles of sentencing provided for in Art. 65 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, as well as the criteria developed by practice, including:

- the sizeof the bribe received;

- the amountof the damage caused;

- committing an offense undermercenary motives (in particular, the amount of a bribe is UAH 5,000);

- significantpublic danger of the offense and its special graveness;

- the property statusof the accused, etc.

But judges do not always use such arguments. For example, the HACC ordered the full confiscation of property of a convicted judge of the Babushkinskyi District Court of Dnipro for receiving a bribe of USD 15,000 since “this type of punishment is directly provided for in the sanctions of these articles.” This is not the only case when HACC judges do not resort to a clear explanation of the reasons for applying a certain amount of confiscation.

There are other examples. In the case of bribery of the acting head of the State Agency for the Management of the Exclusion Zone by the ex-director of the State Enterprise Association Radon, the court decided to confiscate all property except housing since the accused had two minor children. A similar situation was in the case of embezzlement of the property of PJSC Agrarian Fund, where the convicted person’s house was not confiscated due to the fact that 5 people lived in it.

In certain cases, special attention is paid to the role of the convicted person during the commission of an offense. Therefore, often the perpetrators of crimes are ordered the confiscation of all property, while the accomplices get half of their property confiscated.

HACC judges do not always impose confiscation of property even in cases where it is defined in the sanction of the article as an additional, but not mandatory punishment. This can be explained by the fact that confiscation (as a general rule) is imposed when a grave or especially grave mercenary offense has been committed. It can also be imposed for offenses against the foundations of the national security of Ukraine and public safety, regardless of their graveness.

The choice whether to impose confiscation is granted to the court by the sanctions of Articles 365-2 and 369 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. Judges do not clearly establish in all cases whether the accused receives any property advantage from the commission of an offense.

For example, in the case regarding the accusation of a Poltava Regional Council member and one of the managers of the ME Poltavapharm in providing police officers with a bribe of UAH 35,000, the court did not establish the facts of enrichment of convicted persons from the offense, so it did not impose confiscation on them. The court also took into consideration the presence of dependants.

In contrast, in the case of a Moldovan citizen who was found guilty of bribing a military prosecutor for lifting the arrest of the Sky Moon vessel, the court found that the offense was mercenary, but did not impose confiscation.

Thus, the practice of imposing a punishment in the form of property confiscation is not sustainable, which creates legal uncertainty and the risk of abuse.

HACC judges do not always impose confiscation of property even in cases where it is defined in the sanction of the article as an additional, but not mandatory punishment. This can be explained by the fact that confiscation (as a general rule) is imposed when a grave or especially grave mercenary offense has been committed.

How does the property confiscation of top corrupt officials replenish the national budget?

As of December 31, 2023, there were 24 HACC verdicts in the public domain, which entered into force and which were intended to confiscate property. But the verdict and its entry into force are only the first steps in the procedure for enforcing the sentence.

The procedure for the enforcement of a sentence in terms of confiscation consists of several steps provided for by the Procedure on the organization of enforcement of decisions.

Firstly, the court has to draw up a writ of execution and send it along with a description of the convicted person’s property (if any) to the enforcement service. After that, the state executor must open enforcement proceedings. The High Anti-Corruption Court usually quickly draws up such writs and sends them for enforcement, as the period from the date of entry into force of the sentence and the opening of enforcement proceedings in most cases does not exceed 30 days.

Next, the executor seizes the property that will be subject to confiscation. In addition, the executor can search for property that can be confiscated by sending queries or analyzing databases.

The procedure for the enforcement of a sentence in terms of confiscation consists of several steps provided for by the Procedure on the organization of enforcement of decisions.

Search for property that can be confiscated

Executors are often limited in their ability to obtain information about the property of convicted persons, in contrast to law enforcement officers who have public and secret investigative (search) actions at their disposal and can also apply to the ARMA for this purpose.

However, the quality of the Agency’s asset tracing is also difficult to verify due to the lack of the necessary statistics. In addition, the practice of the ARMA to report on the recovered property on its own website allows for the expression of doubts about the possibility of effective seizure and confiscation. This is despite the fact that the Agency, at our request, did not want to share information about the volume of property that is searched for in cases where the HACC adopted final decisions.

An important role in the quality of property search by state executors is affected by problems with administrative powers and the quality of their use. We are talking primarily about problems with access to certain registers and databases, the complexity of communication, etc., which Human Research has already analyzed in the Report on the results of the study of the field of enforcing decisions of courts and other bodies in Ukraine.

For its part, the State Enforcement Service within the framework of enforcement proceedings has the opportunity to seize property without hindrance, but before that it must be found and described.

Executors are often limited in their ability to obtain information about the property of convicted persons, in contrast to law enforcement officers who have public and secret investigative (search) actions at their disposal and can also apply to the ARMA for this purpose.

Seizing the searched assets is a challenge

Of course, one should not hope that the property of the defendant, not seized after a suspicion notice was served, will remain in their ownership after the verdict entered into force. That is why Article 170 of the Criminal Procedure Code of Ukraine imposes on an investigator the obligation to search for all property that can be confiscated in the future, as well as to apply to the court with a motion to seize these assets.

Public data indicate that at least in 5 cases out of 44 publicly available decisions where the HACC delivered a verdict with confiscation, the property of suspects or accused was not seized.

For example, in the case of extortion by an SSU employee of a bribe of USD 55,000, the HACC ordered confiscation of all his property, but there is no information about the seizures of such assets in this proceeding. The absence of restrictions on the disposal of property is also indicated by the fact that the judges in the verdict did not decide on the fate of the seizures. We see a similar situation in the case against a judge of the Kalanchak District Court, convicted of bribery, and a similar case against a judge of the Mukachevo City District Court. Moreover, according to the declarations of the latter, he owned money savings, and while the cases were heard, he sold his car and bought another one, but registered it to a relative.

The lack of property seizures is a serious problem. Persons involved in cases, when they learn about their status, can alienate and take other actions to avoid punishment in the form of confiscation. Under such conditions, it is difficult to imagine that the state executive service is searching for and seizing property.

A similar situation occurred in one of the NABU cases, but then the Bureau had the authority to apply to the court with claims for invalidation of agreements. The case reached the Supreme Court, where the judges recognized that the conclusion of contracts should not be used to avoid a seizure or possible confiscation. It upheld the claim of the NABU despite the fact that by the decision of the CCU, after filing a claim, the fact of a pre-trial investigation body having such powers was declared unconstitutional.

Considering the legal positions of the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, SAPO prosecutors need to counteract such cases of withdrawal of property from possible confiscation through the instruments of agreement invalidation.

But with special confiscation, such problems can be avoided because under Art. 96-2, part 4 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, property can be confiscated from a third party, if they knew or should have known and could have known that such property could be subject to special confiscation.

Public data indicate that at least in 5 cases out of 44 publicly available decisions where the HACC delivered a verdict with confiscation, the property of suspects or accused was not seized.

Public data on confiscated property are barely collected

The quality of enforcing confiscation decisions is also difficult to verify. When researching this topic, we sent more than 20 inquiries about the results of enforcing HACC sentences to the regional executive services. But most of them refused to provide us with any information about how much property the national budget received from confiscating incomes of top corrupt officials.

By the way, the HACC statistics has a column with the value of property confiscated from convicted persons, but it is empty in all five reports. Such information is provided in the reports of the NABU, but without information on how much money was received after the sale of these assets.

Information about the revenues received from the confiscation of property to the national budget could be obtained from the ARMA if such assets were transferred to it for management. In such cases, it is the ARMA that deals with their sale.

The ARMA register of seized assets shows one case where assets at the stage of pre-trial investigation were transferred to the Agency for management, and it concerns the embezzlement of UAH 25 million of SE Eastern Mining and Processing Plant. In this criminal proceeding, the corporate rights of LLC Trading House Eco-Service belonging to one of the convicted persons were seized. Therefore, the ARMA must sell these corporate rights on one of the Prozorro.Sale platforms. However, this information is not available in the asset register and neither are the data on which assets were seized in most of the criminal cases we analyzed.

If the property has not been transferred to the ARMA, then it is managed by the executive service, in accordance with a special Procedure. The fate of such property can be different: it can be transferred to the ownership of the state, sold, transferred free of charge to hospitals, schools, orphanages, etc., or destroyed.

While researching, we have found that the enforcement of confiscation is a long process, and currently, out of 24 sentences that have entered into force, only 5 have been enforced in terms of confiscation, as evidenced by the completion of enforcement proceedings. 17 enforcement proceedings are still ongoing, and in 2 cases, enforcement proceedings have not even been opened as of the beginning of 2024.

In cases where the property of convicted persons was sold on the Open Market site, there are no particularly impressive results either. For example, the car of Kostiantyn Starovoit, ex-director of OJSC Kirovogradgaz (a subsidiary of Tsentrgaz), convicted of embezzlement of property, was sold at an auction at a starting price of UAH 265,018. For example, a third part of the apartment confiscated from the above-mentioned Anton Haidur, ex-judge of the Mizhhiria District Court of Zakarpattia oblast, was bought by Yurii Haidur at the starting price.

Thus, the enforcement of property confiscation is a long process. Its effectiveness remains doubtful, at least due to the fact that the executive service bodies are in no hurry to share information on how many assets were sold as a result of enforcing specific sentences. Long periods of time between the entry of the sentence into legal force and the actual sale of the asset can also adversely affect its value.

Information about the revenues received from the confiscation of property to the national budget could be obtained from the ARMA if such assets were transferred to it for management. In such cases, it is the ARMA that deals with their sale.

Unused opportunities for special confiscation

The value of property to which the HACC judges applied special confiscation is growing. This is a positive trend because most of the special confiscated property is money seized, which was usually the subject of criminal proceedings or obtained as a result of committing an offense. The exception is the case of Dmytro Sus, the investigator of the Prosecutor General’s Office, where the panel of HACC judges collected gaming machines and other equipment that the convict wanted to seize into the national income.

The HACC declares that it managed to collect more than UAH 370 million to the budget, and 90% of this amount was received in 2023 alone.

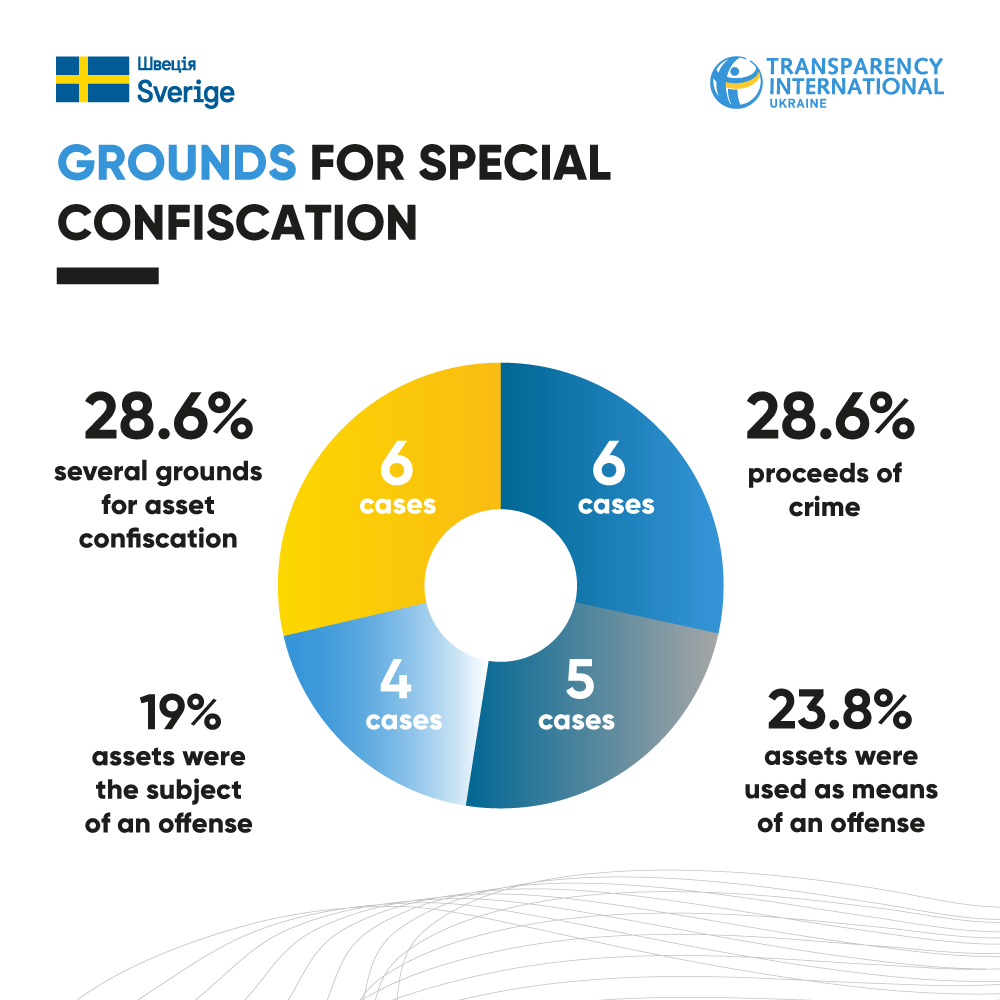

The grounds for special confiscation are defined in the Criminal Code of Ukraine. To simplify, such a means of criminal legal influence can be used if the assets:

- were obtained due to an offense (Article 96-2, part 1, clause 1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) — 6 cases;

- intended to finance an offense (Article 96-2, part 1, clause 2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) — 0 cases;

- were the subject of an offense (Article 96-2, part 1, clause 3 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) — 5 cases;

- were used as means or instruments of an offense (Art. 96-2, part 1, clause 4 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) – 4 cases.

In 6 cases, there were several grounds for confiscation of assets at once.

The legality of the special confiscation was to be appealed in the Constitutional Court of Ukraine. But in late June 2022, the constitutional justice body recognized that the articles on special confiscation of property did not violate the constitutional guarantees of protection of property rights and did not contradict the Fundamental Law.

The use of special confiscation should be convenient because when the defendant has sold or transferred property to someone, it can still be confiscated. To do this, it is necessary to prove that this third party knew or should have and could have known about the connection of the property with the criminal proceedings.

This was the case with SE Eastern Mining and Processing Plant. The judges of the HACC confiscated the funds that the state-owned enterprise transferred to the accounts of LLC Trading House Eco-Service because the director of the LLC was an accused who knew about the criminal origin of this money.

In addition, the justified use of special confiscation should not cause problems with the enforcement of sentences in this part abroad. The HACC has cases where final verdicts have not yet been delivered, but the property has been seized in foreign jurisdictions. It is on the quality of the prosecution’s position and the reasoning of the court decision that the possibility of confiscation of assets abroad, if the court decides on a conviction, will depend.

Often, the provisions of Art. 100, part 9, clause 6-1 of the Criminal Procedure Code of Ukraine, which establish the possibility of confiscation of property belonging to a convicted person for committing a corruption offense, legalization (laundering) of proceeds from crime, their related party, are also ignored by law enforcement officers if the legality of the grounds for acquiring rights to such property is not confirmed in court.

Therefore, the use of this provision in cases of money laundering and corruption crimes should be enhanced and the problems that prevent this should be addressed.

The use of special confiscation should be convenient because when the defendant has sold or transferred property to someone, it can still be confiscated. To do this, it is necessary to prove that this third party knew or should have and could have known about the connection of the property with the criminal proceedings.

Conclusions and recommendations

As we can see, the confiscation of all property of corrupt officials does not justify its existence. This mechanism can potentially be recognized as unlawful; it does not generate significant revenues to the national budget, and also contains a number of risks of abuse both at the stage of seizure of property and at the stage of enforcing this punishment.

To deprive corrupt officials of the purpose of their existence — illicit enrichment — it is necessary to develop the institution of special confiscation, as well as confiscation not within the framework of criminal proceedings. This requires additional efforts on the part of the prosecution to prove the criminal origin of the property, but we are confident that such efforts will be rewarded.

To achieve such goals, efforts should be made to change the legislation and the practice of its application. Namely:

- to remove unconditional confiscation of all or a part of property as punishment from the criminal law. This point does not meet international standards for the protection of human rights because it is clearly disproportionate. In addition, it will complicate the enforcement of such a punishment if it concerns property abroad;

- to strengthen the work of law enforcement agencies in terms of proving the origin of the seized property: whether it is a means or instrument of an offense or was acquired as a result of an offense. Effective special confiscation is a tool that complies with the Constitution of Ukraine and international standards for the protection of human rights;

- to strengthen the quality of the search for assets that can be seized within the framework of criminal proceedings with the collection of proper evidence of their criminal origin to timely and effectively seize such assets for the purpose of special confiscation;

- to improve the quality of filling the Unified Register of Seized Assets, which will unify the practice of law enforcement agencies in this part;

- to increase the transparency of the work and the capacity of the executive service bodies to confiscate property. These agencies perform almost the same functions as the ARMA, only for a much larger number of assets, but access to information about their work leaves much to be desired.

Effective confiscation of criminal property should become a high-quality tool for anti-corruption because in this case, the person will lose the main incentive to commit offenses — financial gain.

To deprive corrupt officials of the purpose of their existence — illicit enrichment — it is necessary to develop the institution of special confiscation, as well as confiscation not within the framework of criminal proceedings.

The study was developed by

Head of Legal Department: Kateryna Ryzhenko, Deputy Executive Director for Legal Affairs Transparency International Ukraine

Authors of the study:

Pavlo Demchuk, Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine

Andrii Tkachuk, Junior Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine

This publication was prepared by Transparency International Ukraine with the financial support of Sweden.