This research is made possible with the support of the MATRA Programme of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ukraine, and with the financial support of Sweden within the framework of the program on institutional development of Transparency International Ukraine. Content reflects the views of the author(s) and does not necessarily correspond with the position of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ukraine or the Government of Sweden.

In 2025, the Transparent Cities program announced the discontinuation of the Transparency Ranking of the 100 largest cities and launched a new study assessing how prepared Ukrainian municipalities are for EU integration. The criteria of this new assessment are aligned with the requirements and recommendations of key policy documents, including the Council of Europe’s Principles of Good Democratic Governance, the Ukraine Facility Plan, and the European Commission’s Reports under the 2023–2024 EU Enlargement Package, among others.

During the piloting of this new analytical format, the openness of 11 municipalities was already assessed using European approaches. The second stage focused on evaluating the level of development of the electronic services ecosystem offered by local self-government bodies.

As the level of government closest to communities, local authorities are responsible for delivering a wide range of essential public services in such critical areas as healthcare, public transport, urban amenities, housing and utility services, social protection, and administrative services. Their influence on the development of electronic services must therefore be both strong and long-term. The European Union assesses the digital transformation of public services through the lens of nine key life events that depend on these services (family, education, health, transport, relocation, career, initiation of small claims procedures, starting a business, and conducting regular business activities). Electronic services can significantly strengthen the transparency of municipal operations, become indispensable tools for urban planning, and serve as a powerful incentive for citizens to engage in decision-making processes or provide feedback to authorities.

As for Ukraine, the historical circumstances of the past decade — occupied territories, hundreds of thousands of mobilized citizens, tens of thousands of people with acquired functional impairments, millions of internally displaced persons, daily damage to or destruction of property, loss of documents, business relocation, and distance learning — have made the creation of high-quality electronic services at the municipal level one of the highest priorities. During wartime, secure and user-friendly access to such services from any location, without significant time spent searching for information or the need to visit structural units of local self-government bodies, municipal enterprises, or institutions, has become a matter of survival for both city residents and entrepreneurs.

During the war, safe and easy access to electronic services from any location, without significant time spent searching for information, has become a matter of survival for both city residents and businesses.

Research methodology

The methodology of the Euroindex provides for a shift from one-off annual measurements to continuous monitoring. Analysts will record changes in transparency and accountability of city councils several times a year. That will be a step-by-step research with thematic blocs — openness of city councils, e-services, open data, use of budget funds, prevention of corruption, and so on. Each step will be supported by a separate methodology, with simultaneous announcement of results.

Within the electronic services block, the emphasis was placed on the requirements of the Ukraine Facility Plan, primarily with regard to the reforms outlined in the sections Decentralization and Regional Policy, Digital Transformation, and Human Capital. In particular, this concerned reforms such as Digitalization of Public Services, Advancing Decentralization Reform, Strengthening Citizen Engagement Tools in Local Decision-Making Processes, and Improving Social Infrastructure and Deinstitutionalization. The provisions of the EU Digital Decade 2030 program were also taken into account, as it defines four key areas of the European Union’s digital transformation by 2030: digital skills, digital infrastructure, digital business, and digital public services.

The term electronic services may refer to a very broad range of online resources, from simple informational websites to large-scale online platforms engaging millions of users each month (online marketplaces, social media, content-sharing platforms, app stores, etc.). Within this study, however, the scope was significantly narrowed. The analysis focused on whether city councils provide access to services that function either as built-in interactive elements of websites or mobile applications (such as interactive maps, interactive dashboards, and web forms) or as standalone interactive online services (primarily information and analytical systems, mobile applications, and chatbots). In other words, the assessment did not examine the mere availability of informational content, but rather the availability of functional tools enabling interaction with data and the execution of specific actions.

Information on cities’ performance against electronic services–related indicators was collected by analysts in October 2025. In certain cases (protective shelters, barrier-free facilities, remaining stocks of medicines, etc.), it was essential that services provided access to data that were up to date as of 2025. In other cases, data currency was deliberately not verified, or it was taken into account that data updates depend on user activity rather than on municipal authorities.

The assessment criteria did not require all services to be initiated or funded by local self-government bodies. Over recent years, central executive authorities, businesses, civil society organizations, and charitable foundations have initiated the development of dozens of interactive online services in Ukraine that enable access to a wide range of services. Accordingly, the methodology allowed for the fact that city councils may not design services “from scratch” but instead ensure citizens’ access to solutions developed with state funding, private investment, or international grants.

The pilot sample included city councils of ten regional capitals (Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Kropyvnytskyi, Lutsk, Lviv, Odesa, Poltava, Kharkiv, Khmelnytskyi, and Chernihiv), as well as the city of Kyiv. The selected cities represent various levels of transparency, cover all macro-regions of Ukraine, and reflect different wartime contexts (rear-area cities and cities included in the List of Territories of Potential Hostilities).

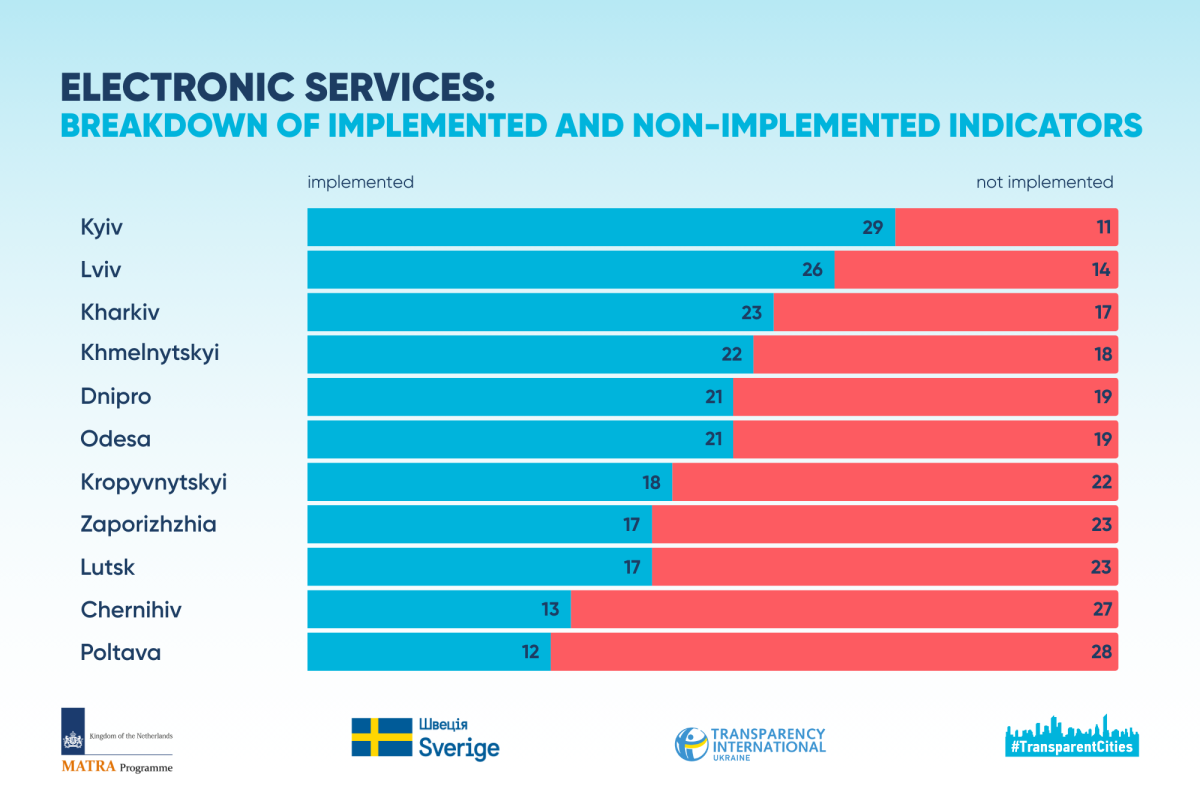

The level of development of the electronic services ecosystem was assessed against 40 criteria. The final score was calculated by summing all points awarded to a city across these indicators. The maximum possible score a city could receive was 100 points.

The analysts examined:

- whether the city has a valid, approved, and up-to-date informatization program;

- whether access is ensured to services that enhance the transparency of municipal operations, improve service delivery in the areas of safety, education, healthcare, transport, utility services, environmental protection, etc., or function as tools of e-democracy;

- the availability of a comprehensive mobile application aggregating digital mobile services that help address citizens’ everyday needs;

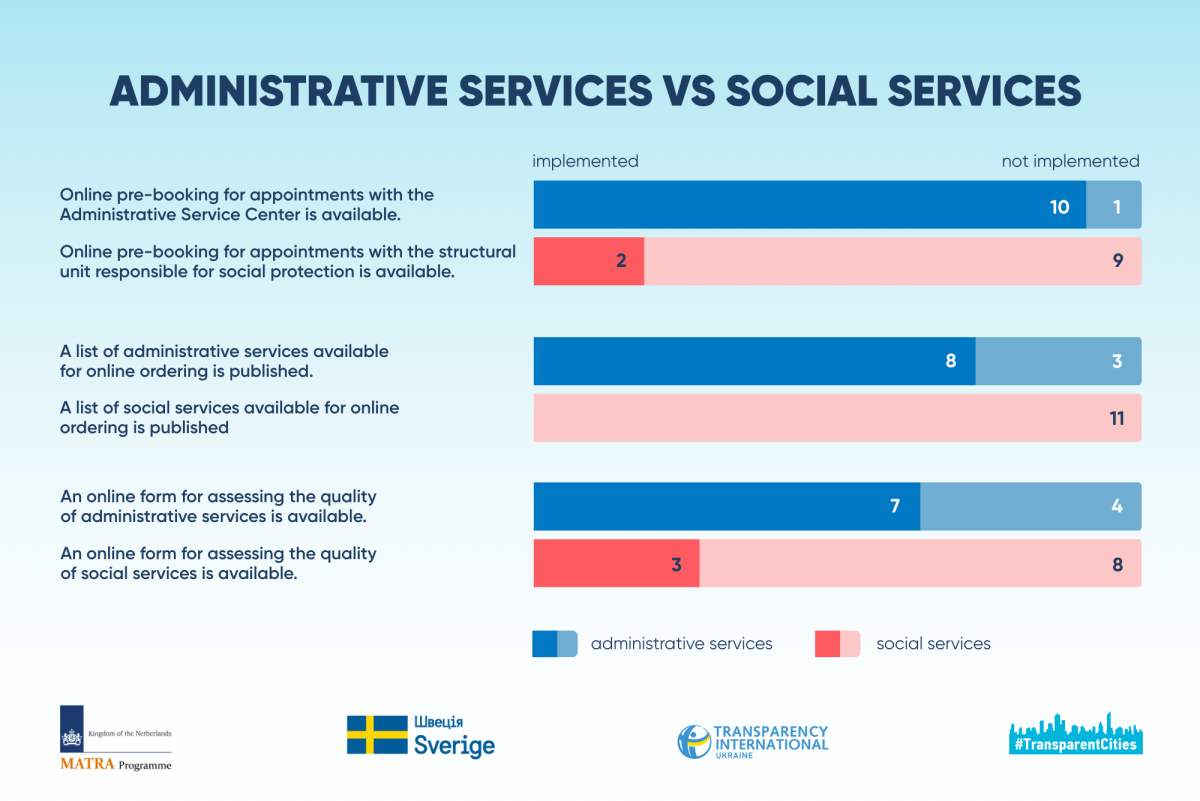

- the publication of information on administrative and social services available for online ordering;

- the possibility to book appointments online with Administrative Service Centers, structural units responsible for social protection, as well as the availability of online services for assessing the quality of services provided by these bodies.

The analysis of indicators related to administrative and social services was based on the provisions of the Laws of Ukraine on Administrative Services and on Social Services, as well as the Order of the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine on Approval of the Classifier of Social Services. These indicators did not place emphasis on distinguishing between state and municipal services.

Important note. During the assessment, analysts verified whether a single point of entry existed — namely, a dedicated specialized website of the city council or a separate thematic section on the official website of the local self-government body, consolidating accurate links to available electronic services. However, unlike the previous stage — the openness assessment — analysts continued to record the presence or absence of electronic services even in cases where such a single point of entry could not be identified. Otherwise, cities would not have received a comprehensive analysis of their strengths and weaknesses, and experts would have lacked a basis for developing recommendations and road maps for change. Nevertheless, in future monitoring rounds, Transparent Cities analysts plan to apply the single point of entry principle and expect that most local self-government bodies will consolidate links to all recommended services in one place on their official websites.

The pilot sample included city councils of ten regional capitals (Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Kropyvnytskyi, Lutsk, Lviv, Odesa, Poltava, Kharkiv, Khmelnytskyi, and Chernihiv), as well as the city of Kyiv.

Research results

The average level of implementation of 40 indicators in the Electronic Services block stands at 49.8%.

Kyiv achieved the highest score, with 70 out of 100 possible points. One position below is Lviv with 63 points, followed by Kharkiv with 58 points. The lowest scores were recorded for Poltava (27 points), Chernihiv (32 points), and Lutsk (43 points).

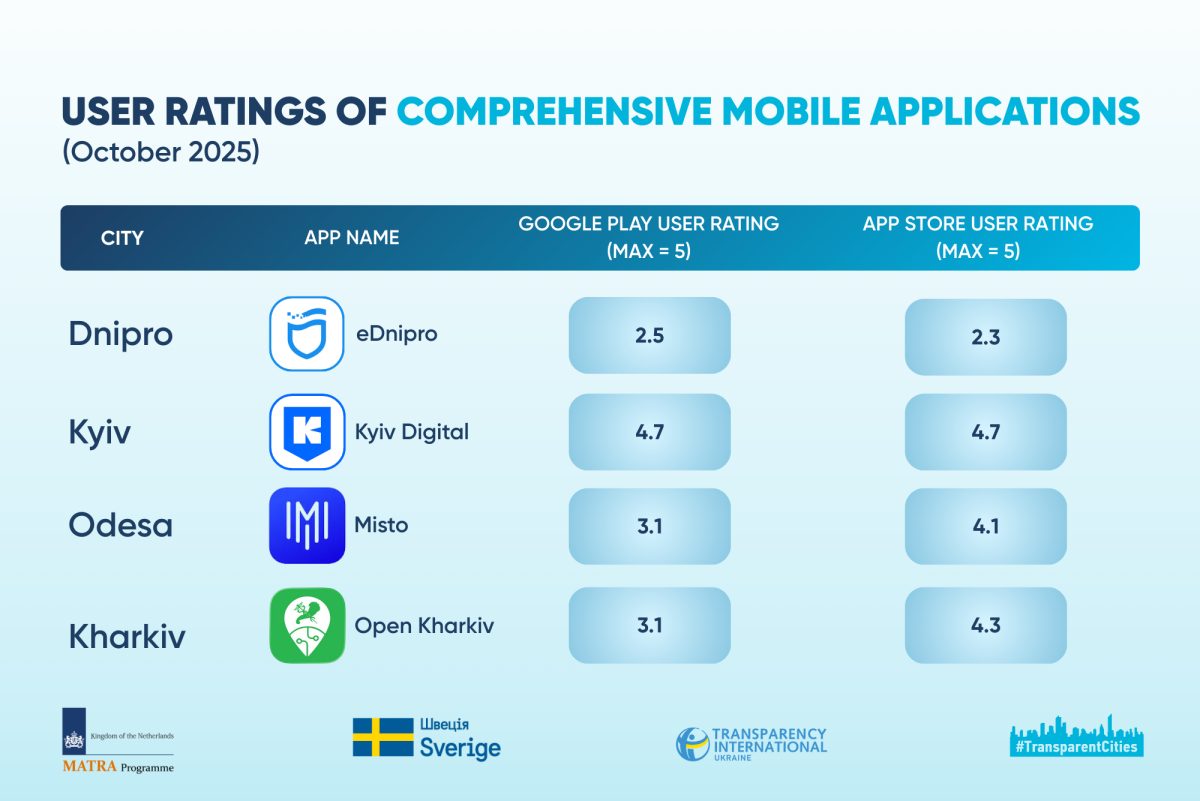

The leadership of Kyiv and Lviv was predictable. In the UN Local Online Service Index 2024, which assesses e-government in the most populous city of each of the 193 UN Member States, Kyiv ranked 13th and was classified among cities with a very high LOSI score. Lviv, in turn, was shortlisted as a finalist of the World Smart City Awards 2025 in the Governance & Economy Award category. Within the Transparent Cities study, however, the key factor that led to a substantial gap between these two cities was Lviv’s lack of a comprehensive mobile application. As a result, Lviv was unable to score any points against the indicators related to this component, accounting for a total of 14 points.

By contrast, Kharkiv’s third-place ranking was far less predictable. Prior to the full-scale invasion, Kharkiv significantly outpaced other IT locations in Ukraine in terms of the number of IT specialists, second only to the Kyiv hub. In 2020, the city also won the Best Digital City category at the Smart City Awards held as part of the Kyiv Smart City Forum. However, Kharkiv is now a frontline city and one of the regional capitals most affected by the war; only 4% of Ukrainian IT professionals currently live and work there, compared to 14% in 2021. The study shows that the city authorities have managed not only to maintain electronic services developed before the war but also to create new ones (such as the Open Kharkiv mobile application). This capacity for continuity and innovation is what enabled Kharkiv to achieve such a strong result.

In addition to Kharkiv, the study included another city designated as a territory of potential hostilities — Zaporizhzhia. While the municipalities received different scores, both demonstrate, despite the extremely challenging conditions of war, a clear willingness and capacity to develop their own electronic services ecosystems. In the summer of 2025, the municipal enterprise Center for Information Technology Management launched the Digital Zaporizhzhia online platform. The ambition behind this initiative is significant: to consolidate all of the city’s digital services and offerings in one place, thereby applying a European approach to the disclosure and arranging of information.

An analysis of whether city councils have current, approved informatization programs showed that only three regional capitals lack such a program — Poltava, Chernihiv, and Lutsk. In Poltava and Chernihiv, no references to an informatization program could be found at all. In Lutsk, a draft SmartLutsk program for 2025–2029 has been published on the city council’s website; however, as of October 2025, it had not yet been approved. Notably, these three cities also recorded the weakest results in the study. The cases of Poltava and Chernihiv demonstrate that, in the absence of a strategic document defining priority areas and objectives for the digital development of a territorial community, such development becomes fragmented and the continuity of achievements cannot be ensured. Two examples illustrate this lack of continuity. First, the Poltava Open Data Portal, established with the support of Germany and Switzerland, remains operational, yet the most recent statistical data available on the platform date back to 2023. Second, with support from the Netherlands, the ePoltava mobile application was developed; however, due to unresolved legal inconsistencies between the city authorities and the developer, access to the application has been unavailable since 2023.

Kyiv achieved the highest score, with 70 out of 100 possible points. One position below is Lviv with 63 points, followed by Kharkiv with 58 points. The lowest scores were recorded for Poltava (27 points), Chernihiv (32 points), and Lutsk (43 points).

Strengths and weaknesses

All 11 cities covered by the study provide access to electronic services for real-time tracking of municipal public transport, as well as to electronic local petition platforms. Also, all regional capitals offer online enrolment services for kindergartens and enable parents to monitor waiting lists remotely.

All cities included in the study, with the exception of Kropyvnytskyi, have introduced cashless fare payment in municipal public transport (via QR codes, contactless NFC payments, or virtual transport cards), as well as the option to book appointments with Administrative Service Centers online.

Nine out of the 11 regional capitals provide communication through electronic contact centers —analytical and communication systems designed to receive, process, and monitor the handling of citizens’ requests concerning issues that require prompt response. The only exceptions are Kropyvnytskyi and Poltava.

All 11 cities covered by the study provide access to electronic services for real-time tracking of municipal public transport, as well as to electronic local petition platforms.

However, none of the city councils published, on their official websites or on the websites of structural units responsible for social protection, a separate list of social services available for online ordering by citizens. While digital transformation has already taken place in the field of administrative services (lists of administrative online services can be found on the websites of Administrative Service Centers in 8 out of 11 cities), the sphere of social services has so far been largely bypassed. Notably, at the national level, specialized electronic services have been developed — the Social Portal of the Ministry of Social Policy and the Electronic Account of a Person with a Disability, which allow users to submit applications for services online. However, links to these services are published only on the websites of Kropyvnytskyi, Kharkiv, and Khmelnytskyi, primarily within news items.

Another unexpected finding of the study was the absence, on the homepages of official local self-government body websites, of links to pages dedicated to comprehensive city mobile applications with lists of available services. In total, four such applications are currently in operation: e-Dnipro (Dnipro), Kyiv Digital (Kyiv), Misto (Odesa), and Open Kharkiv (Kharkiv). However, only the homepage of the official website of the Odesa City Council contains a link to the Misto application. Even in this case, the link leads to a website where it is impossible to find clear information on which services are already available to residents and visitors of Odesa. As for the homepages of the Dnipro City Council, Kyiv City Council, Kyiv City State Administration, and Kharkiv City Council, as of October 2025 there were no references to city mobile applications at all.

Ten regional capitals do not provide access to an e-service for searching for medical equipment in municipal healthcare institutions (the only exception is Kropyvnytskyi), nor do they offer any electronic service with up-to-date data on energy management or energy monitoring (the only exception is Kyiv). Nine out of 11 cities do not provide access to an electronic service for searching for medicines purchased with public funds in municipal healthcare institutions (exceptions are Kyiv and Odesa). It should be noted that city councils are not required to collect data on medical equipment, medicine stocks, or consumption of utility services specifically for the purpose of creating electronic services based on them. Local authorities are required to disclose and in most cases, regularly do disclose such data on the Unified State Web Portal of Open Data, in accordance with Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No. 835.

In addition to issues related to the availability of services, analysts also recorded difficulties in determining the timeliness of the data provided by certain services. For example, according to the study, 7 out of 11 city councils do not provide access to up-to-date interactive maps of civil protection shelters, which is critically important in the fourth year of the war. In Kropyvnytskyi and Poltava, it was not possible to find any links to such maps on official websites at all. In five other city councils, access to the maps was provided; however, it was impossible to verify whether the data had been updated in 2025.

As regards the application of the single point of entry principle, compliance with this indicator was recorded in only 5 out of 11 cities — Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Kropyvnytskyi, Lutsk, and Khmelnytskyi. None of the leaders — neither Kyiv, nor Lviv, nor Kharkiv — have created dedicated sections on their official websites where users could easily find up-to-date links to dozens of electronic interactive services developed by these cities on their own initiative over recent years.

Key findings and recommendations

A clear correlation can be observed between the absence of an approved informatization program and low results in the comprehensive assessment of electronic services.

The 11 analyzed cities demonstrate very different levels of development of electronic services ecosystems. While the range of openness assessment results for this sample was 28 points, the gap between the highest and lowest scores in the second block amounted to 43 points. This disparity can be explained by the fact that, unlike indicators related to electronic services, many openness indicators are direct requirements of Ukrainian legislation, which city councils cannot ignore.

The single point of entry principle, which is an element of European governance, is applied selectively. Confusion is sometimes observed in the use of the terms services and public services.

At the same time, clear progress can be seen in the development of digital services supporting the implementation of the Ukraine Facility Plan in the context of reforms such as Improving Preschool Education, Comprehensive Planning of Transport Sector Development, Strengthening Citizen Engagement Tools in Local Decision-Making, and Digitalisation of Public Services. Thanks to these services, residents of regional capitals have access to simple and user-friendly solutions in the areas of education, transport, administrative services, and urban amenities, as well as opportunities to participate in local e-governance.

At the same time, there are significant challenges related to digital services in the areas of local statistics, energy efficiency, healthcare, and social services. This does not contribute to the implementation of the Ukraine Facility Plan with regard to reforms outlined in the Decentralization and Regional Policy, Energy Sector, and Human Capital sections. Most importantly, local self-government bodies are not paying sufficient attention to the development of electronic services in areas whose importance continues to grow each year during wartime.

The program recommends that all cities (not only those included in the pilot sample) take into account the analytical findings, in particular by:

- Systematizing strategic digital planning and developing and approving informatization programs for the next 3–5 years. These programs should define the purpose, priority areas, and specific objectives of digital development of the territorial community, as well as expected results. For communities, informatization programs should become not a formal document but a roadmap to a digital future.

- Conducting an inventory of all existing digital services (information and analytical systems, mobile applications, chatbots, interactive maps, interactive dashboards, etc.), including relevant services offered by the state (e.g. Open Budget, the Social Portal of the Ministry of Social Policy), businesses (e.g. DozoR City, EasyWay), and civil society or charitable organizations (e.g. EDEM: Local Petitions, e-Liky). Links to these services should be consolidated in a single section of the official city council website — a single point of entry for electronic services. Duplication should not be avoided: for example, if municipal hospitals and clinics update data in e-Likyhttps://eliky.in.ua/, links to this service should be available both in the Electronic Services section and on the website or page of the healthcare department.

- Developing basic electronic interactive local statistics services, or, where such services already exist, regularly collecting, processing, and visualizing statistical data. Strategic planning, managerial decision-making, investment attraction, and assessment of local policy effectiveness must be data-driven. Providing access to such data does not necessarily require the immediate creation of a full-fledged local statistics portal, as done by Lviv; it may be sufficient to create a dedicated section with public thematic dashboards on the official city council website and gradually populate it, as Kyiv does.

- Paying due attention to digital transformation in the field of social services. Over 3.5 years of the full-scale invasion, the number of recipients of social services — individuals and families belonging to vulnerable groups and/or facing difficult life circumstances — has increased significantly. Guided by European principles of human-centered and inclusive design, local authorities should extend the existing experience of digital administrative services to the social services sector as soon as possible by:

- ensuring access on the website of the social protection unit to online pre-booking for appointments with its departments (example: Lviv);

- publishing on the unit’s website a table based on the Classifier of Social Services, listing available services, service providers, and indications of whether services can be ordered online or offline;

- creating a dedicated page explaining how to order social services online, with links to relevant national digital services (the Social Portal of the Ministry of Social Policy, the Electronic Account of a Person with a Disability, etc.);

- ensuring access to a web form for assessing the quality of social services provided (examples: Kyiv, Chernihiv).

- Clearly indicating the reference date of data used or displayed in electronic services (day/month/quarter/year). Data currency may be specified either through an explanatory note (e.g. “Dashboard update frequency: daily” for the Petitions dashboard on the Kyiv City State Administration website) or through a copyright notice (e.g. “© 2025 Municipal Enterprise Center for Information Technology Management” on the Zaporizhzhia shelter map).

The program will prepare tailored recommendations for each city council covered by the study, to serve as roadmaps for improving the practical operation of electronic services. The indicator-by-indicator results for each city are available at the link.