In 2025, the Transparent Cities program announced the discontinuation of the Transparency Ranking of the 100 largest cities and launched a new study assessing how prepared Ukrainian municipalities are for EU integration. The criteria of this new assessment are aligned with the requirements and recommendations of key policy documents, including the Council of Europe’s Principles of Good Democratic Governance, the Ukraine Facility Plan, and the European Commission’s Reports under the 2023, 2024, and 2025 EU Enlargement Package, among others.

Analysts have already assessed the openness and e-services of 11 municipalities using European approaches. The third stage focused on evaluating the level of development of the open data ecosystem formed by local self-government bodies.

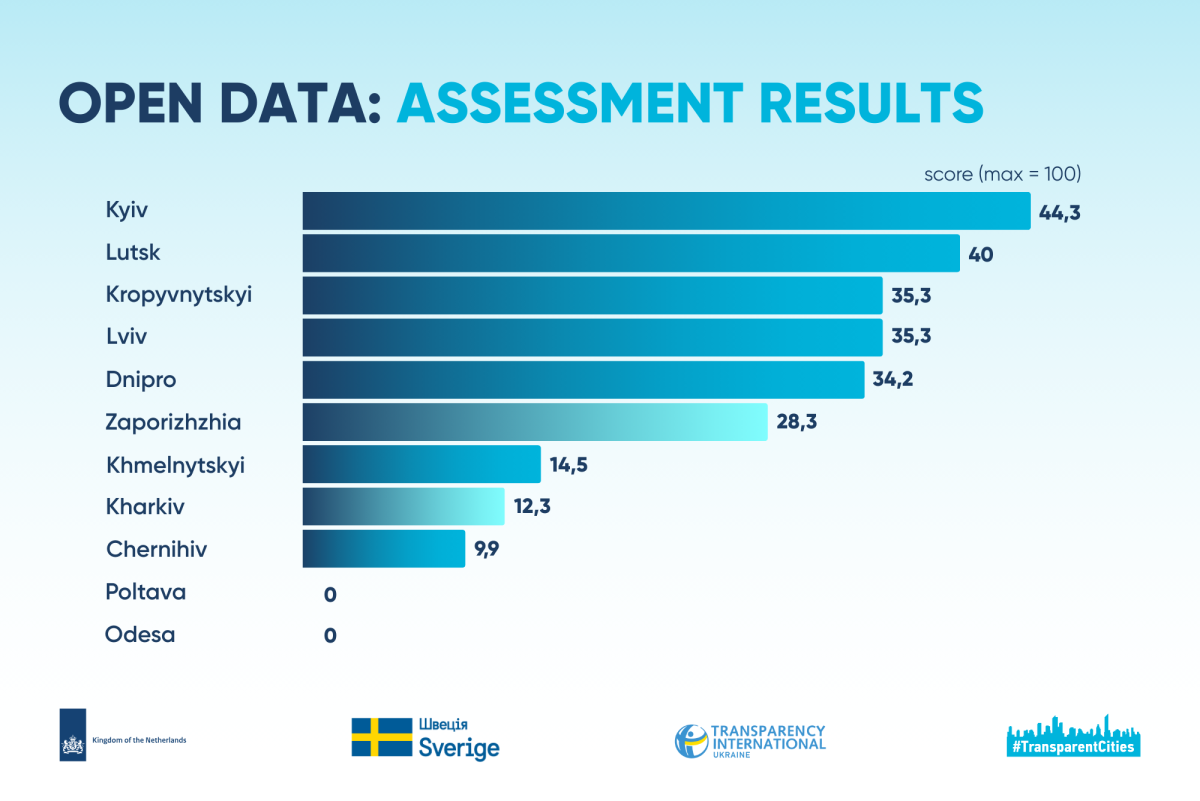

The level of development of the open data ecosystem was assessed using 40 criteria. The final score was calculated by summing all points earned by a city across these indicators. The maximum possible score a city could receive was 100 points.

In particular, the analysts checked:

- whether the official city council website has a dedicated open data section;

- whether that section contains links to key documents defining the city council’s open data policy;

- whether it provides consolidated information on e-services created on the basis of local self-government open data;

- whether the city council has published 30 “EU integration” datasets on the Unified State Open Data Web Portal (data.gov.ua);

- whether the principles of timeliness and interoperability are observed when publishing datasets.

Details of the research methodology are available at the link.

Research results

The average level of implementation of 40 indicators in the “Open Data” block is 23.1%.

Kyiv achieved the highest score, with 44.3 out of 100 possible points. One position below is Lutsk with 40 points, followed by Kropyvnytskyi and Lviv, each with 35.3 points. The lowest scores were recorded by Odesa (0), Poltava (0), and Chernihiv (9.9).

Kyiv owes its leading position to two factors. First, in 2024, the city authorities approved a key regulatory document that incorporated the Ministry of Digital Transformation’s updated recommendations and began systematically populating the Kyiv City State Administration’s account on data.gov.ua in line with those recommendations. Second, unlike Lutsk, Kropyvnytskyi, Lviv, and Dnipro, Kyiv currently publishes its datasets exclusively on the Unified State Open Data Web Portal, so data transfer (harvesting) issues on data.gov.ua did not affect the city’s results.

As for the cities ranked immediately behind Kyiv, Lutsk, Lviv, and Dnipro outperformed the capital in the block of indicators related to open data policy. The critical issue for them, as well as for Kropyvnytskyi, was that the Ministry of Digital Transformation had not established monthly automated transfer of data from local open data portals to the national portal.

The analysts extracted data for the analysis from data.gov.ua on December 5, 2025. As later confirmed in the Ministry’s response to an inquiry from the Transparent Cities program, data transfer from the open data portals of Kropyvnytskyi and Lutsk City Councils was carried out on September 10, 2025; from Lviv City Council, on September 15, 2025; and from Dnipro City Council, on October 28, 2025. As a result, in each of these cities, more than 10 “EU integration” datasets with monthly or weekly update frequency had no chance of passing the verification filter for timely updated resources.

In two regional centers — Odesa and Poltava — which scored zero points in the study, the same key problems were identified: these cities have no dedicated thematic section on their official websites consolidating key open data information, and as of December 5, 2025, the electronic accounts of Odesa City Council and Poltava City Council on data.gov.ua were empty. That said, the operating context of these two cities is very different.

The official website of Odesa City Council is designed so that the number of “Open Data” pages equals the number of local authority structural units. This design approach does not comply with contemporary European approaches to user-centricity and the creation of one-stop shops/single points of contact. Odesa’s results are also driven by the absence of approved key open data policy documents and the lack of centralized oversight over dataset publication.

In Poltava, the context is entirely different. In December 2024, the city council approved the Procedure for Publishing Datasets of Poltava City Council and Its Executive Bodies in Open Data Format. There is also a dedicated website, “Open Data of Poltava City Council,” where up-to-date datasets can be found. However, the municipality did not take the next steps—it did not consolidate all user-relevant information about this area in one place on the official website, and it does not comply with the state requirement to ensure convenient and clear dataset publication on data.gov.ua under the “single window” principle.

Local self-government policy in the open data

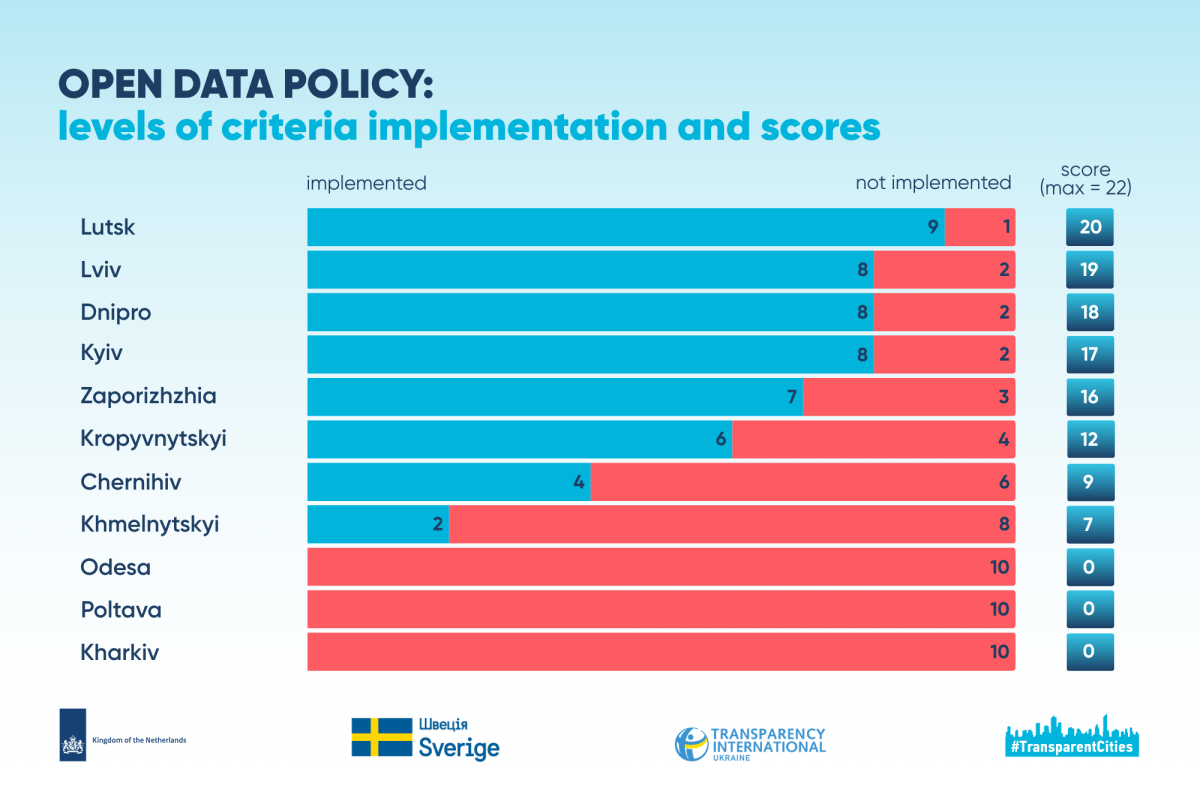

The average level of implementation across the 10 indicators related to local open data policies is 48.8%. The highest result was recorded by Lutsk, with 20 out of 22 points.

The study results showed that 8 of 11 cities have a “single entry point” to open data on their official websites. Only the municipalities of Odesa, Poltava, and Kharkiv failed to provide convenient public access to a section with the relevant information.

7 of 11 city councils published, in that section, links to an administrative act that approved, within the last five years, a unified List of Datasets subject to publication in open data format. The most recent was the order of the Lutsk mayor dated February 26, 2025. All seven documents assign responsibility for each dataset to specific information managers (executive bodies, municipal enterprises, and institutions).

9 of 11 cities paid insufficient attention to the purpose for which data are published—namely, services built on that data. Journalists and researchers can, where needed, download files in CSV/JSON/XML formats, analyze them, and draw appropriate conclusions. But the main purpose of publishing local self-government datasets is to ensure the data are continuously used, including for designing convenient tools for residents (maps, chatbots, mobile applications, etc.). Only the municipalities of Lutsk and Lviv provided links, in their respective sections, to e-services built on their datasets.

As of December, 8 city councils had not published links to decisions on accession to the International Open Data Charter. Some had genuinely not joined it, while Zaporizhzhia, Kropyvnytskyi, and Khmelnytskyi did not provide information on their accession.

In addition, 8 cities do not include, in their approved local self-government List of Datasets, information on the format in which each specific dataset is published. Lack of alignment on this issue at the level of a key policy document leads to recurring problems for information managers during dataset moderation on data.gov.ua, with non-existent formats such as excel, API, and others appearing in resource descriptions. It also makes it easier for municipalities to change publication formats from time to time without considering the problems this creates for regular users.

Open data publication

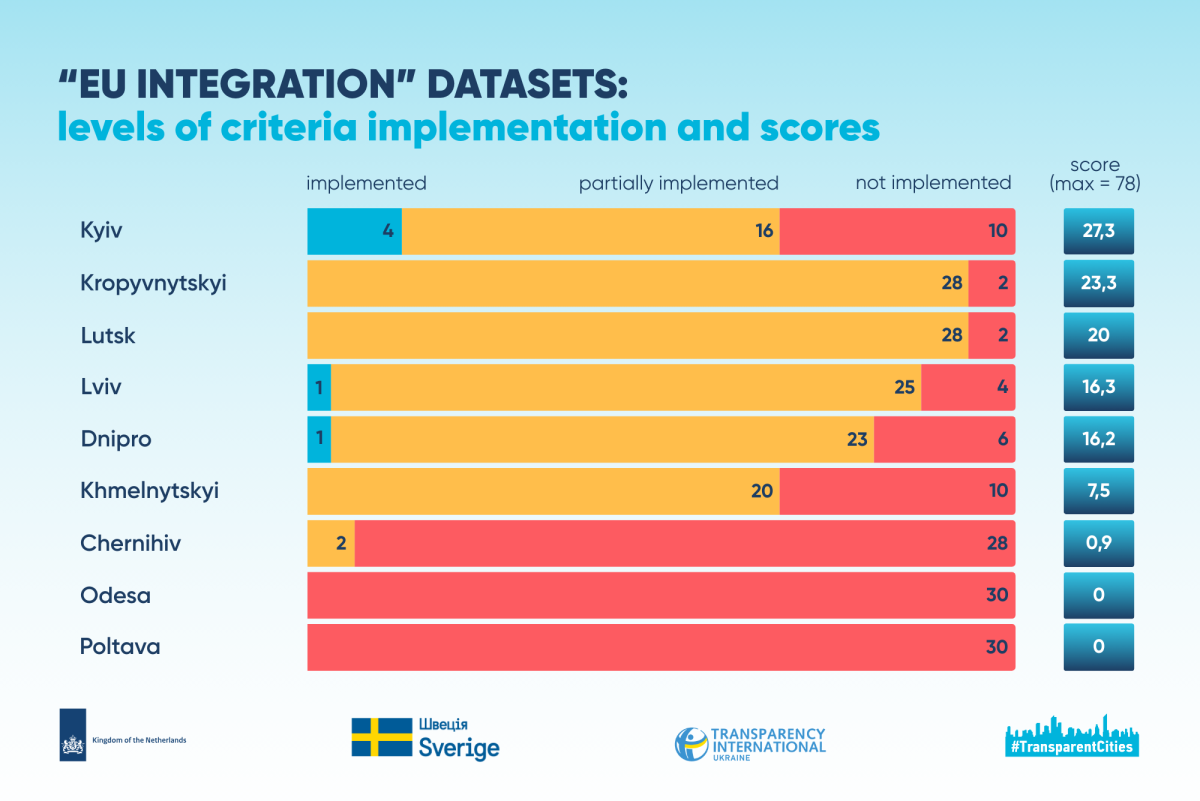

The average level of implementation across the 30 indicators related to publication of “EU integration” datasets in 9 cities (excluding Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv) is 15.9%. The highest result was recorded by Kyiv, with 27.3 out of 78 points.

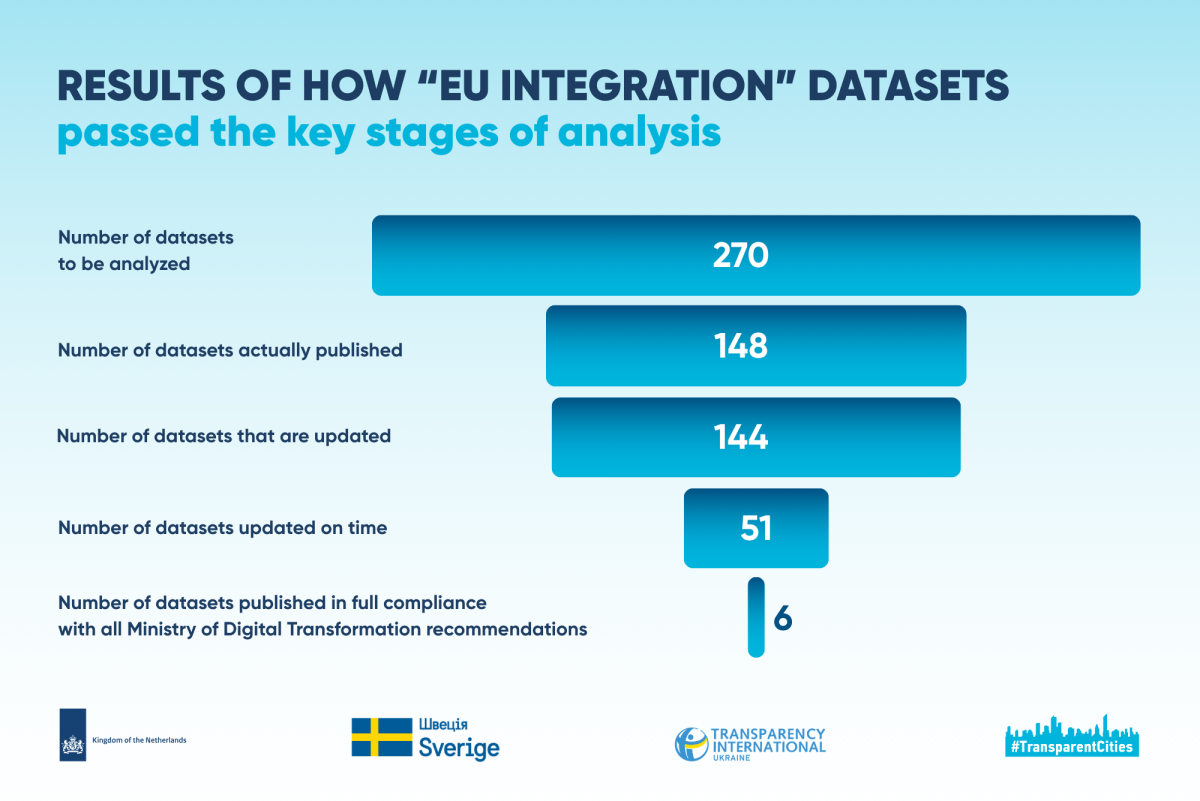

First, the analysts checked whether the required datasets were present. The study found that, of the 270 “EU integration” datasets that city councils were expected to publish in their single electronic accounts on data.gov.ua, 148 (55%) had been published as of December 5, 2025. As for the rest, 112 datasets could not be found at all; in 5 cases, there was no single consolidated city-level dataset; and in another 5 cases, datasets had been formally created but the data were inaccessible.

The largest numbers of “EU integration” datasets were published by Kropyvnytskyi and Lutsk (28 each), followed by Lviv (26). The accounts of Odesa and Poltava City Councils were empty, while the Chernihiv City Council account contained only 2 datasets.

A positive result was that 7 of 9 cities published the dataset “Roll-call results of voting of local council members at plenary sessions of the local self-government body.” The weakest-performing datasets were “Data on the location of electric vehicle charging stations” (published only by Lutsk) and “Data on operational characteristics of buildings of municipal enterprises, institutions, and organizations where energy management systems have been implemented” (available only in Kropyvnytskyi and Lutsk).

At the second step, analysts checked whether the update frequency specified in the files of existing datasets corresponded to the Ministry of Digital Transformation’s recommendations. Matches were recorded in 70 cases, while 97 cases showed mismatches. In one case, analysts had to record partial correspondence, because for the dataset “Lists of legal regulations,” the Kyiv City State Administration specified the recommended update frequency (monthly), whereas Kyiv City Council indicated its own frequency (annually).

The highest number of matches was recorded in Kropyvnytskyi (21 of 28 datasets), while the highest number of mismatches was recorded in Lviv (20 of 26 datasets). In 11 cases, Lviv specified an update frequency not provided for at all in the Ministry’s recommendations—“immediately after changes are made.” In subsequent analysis, timely updates for these datasets were assessed against the Ministry’s recommended frequency. In 4 cases, Khmelnytskyi indicated that the dataset “is no longer updated.”

After that, program experts analyzed whether city councils complied with the timeliness principle. For each of the 144 datasets, they checked whether the datasets contained resources updated on time in accordance with the dataset file. It turned out that only 42 datasets had timely updated resources, while 93 did not. In 9 cases, this check was not performed because the data update frequency was “more than once a day.”

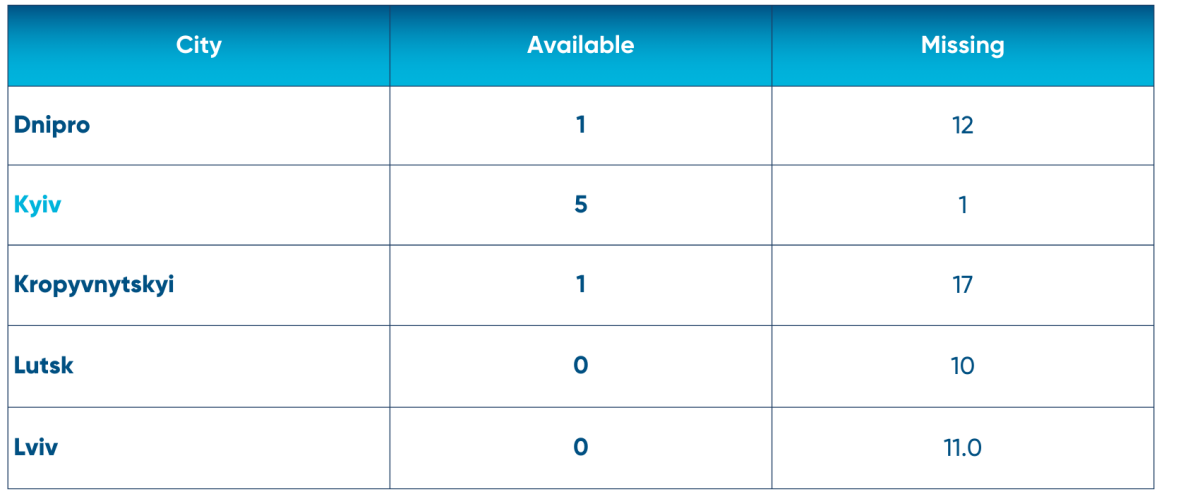

It was at this stage that Kyiv moved into first place. It had 12 timely updated datasets out of 20. Kropyvnytskyi and Lutsk each had 9 out of 28, and Lviv had 7 out of 26.

A major stumbling block was datasets that were supposed to be updated monthly. Of 68 such datasets, 52 belonged to cities that publish data on their own local open data portals (Dnipro, Kropyvnytskyi, Lutsk, and Lviv), after which harvesting to data.gov.ua should occur. The analysis showed that only 2 of these 52 datasets contained timely updated resources: Kropyvnytskyi’s dataset with API endpoints for obtaining data from the e-Liky system, and Dnipro’s dataset “Lists of legal regulations,” whose resources were likely added manually to data.gov.ua rather than transferred via harvesting. By contrast, another monthly Dnipro dataset—“Action plan for drafting legal regulations”—was updated on the local open data portal on November 18, 2025, but on December 5, 2025 it was not counted among timely updated datasets on data.gov.ua because the Ministry had last harvested data on October 28, 2025.

Study leaders: availability on data.gov.ua of timely updated datasets with monthly update frequency as of December 05, 2025.

Accordingly, there are solid grounds to conclude that Kyiv’s rise to first place was driven by the fact that, unlike its main competitors, the capital does not depend on transferring data from its own open data portal to data.gov.ua.

The next four steps aimed to verify whether city councils comply, when publishing data, with one of the most important principles—the principle of interoperability. This principle requires “ensuring interaction, combinability, and compatibility of public information in open data format, including through the use in each dataset of unified identifiers of objects, other object attributes, a unified dataset structure, and unified data resource structures, which makes it possible to compare information within a dataset or resource, as well as with other datasets of the same information manager or other information managers.”

At the fourth stage, program experts analyzed whether timely updated resources fully reflect the dataset structure prescribed by the Ministry of Digital Transformation’s recommendations. This check was meaningful only for datasets that should consist of two or more resources. For example, the dataset “Data on e-petitions” should consist of two resources: petitions (petition data) and votings (data on persons who signed the petition). As a result of checking 15 datasets with timely updated resources, it was found that the structure of only 3 fully complied with the Ministry’s recommendations, 9 partially complied, and 3 did not comply at all.

Next, for each of the 42 timely updated datasets and 9 datasets with an update frequency of “more than once a day,” experts checked whether resource names followed the Ministry’s recommendations. In 18 cases, the recommendations were fully followed; in 12, partially followed; and in 21 cases, not followed at all. It was at this stage that Lutsk finally lost its chance to compete with Kyiv for leadership. It turned out that all Lutsk resources were titled in Ukrainian, whereas English-language names are required.

At the sixth stage, for each of the 42 datasets, analysts checked whether file names of timely uploaded resources followed the Ministry’s recommendations. In 17 cases, the recommendations were fully followed; in another 10, partially followed. If the previous step showed that the Kyiv City State Administration and Kyiv City Council used different languages for resource names (English and Ukrainian, respectively), then at this stage the divergence shifted to Latin-script conventions (for example, where KCSA uploads a file named projects_2025-12-02.csv, Kyiv City Council uses plan-diialnosti-z-pidgotovki-proiektiv-reguliatornikh-aktiv_2025-rik.xlsx), which is why the city’s overall result was assessed as partial implementation.

Finally, at the last step, for each of the 42 timely updated datasets and 9 datasets with an update frequency of “more than once a day,” experts checked whether the structure of timely updated resources included all attributes (fields) specified in the Ministry’s recommendations. It was found that 15 datasets had resources built exactly in line with the recommendations. These included 5 of Kyiv’s 19 datasets and 5 of Lutsk’s 9 datasets. In 8 cases, partial implementation was recorded. The attributes of resources forming 28 datasets differed from those recommended.

As a result, out of the 270 datasets reviewed by the program’s analysts, only 6 (2.2%) are published on time and in line with all recommendations of the Ministry of Digital Transformation. These are 4 datasets from Kyiv, 1 from Dnipro, and 1 from Lviv.

Key findings and recommendations

The average level of implementation by 11 cities of indicators in the “Open data” block (23.1%) was substantially lower than the average levels in other Euro Index blocks—“Openness and public engagement” (53.5%) and “E-services” (49.8%). At the same time, the component related to local open data policy (48.8%) is implemented three times better than the component related to dataset publication (15.9%). Alongside municipalities, responsibility for this result also lies with the Ministry of Digital Transformation and Diia State Enterprise, which is within the Ministry’s management scope, because development of methodological recommendations, timely dataset moderation, and regular harvesting from local portals fall within their competence.

The “single entry point” principle, which is an element of European governance, is actively applied by regional centers when it comes to open data policy. In a dedicated thematic section on the official website, most municipalities provide links to the Regulation/Procedure governing key aspects of local self-government work with open data, as well as to the List of Datasets subject to publication in open data format. In most cases, this List assigns responsibility for specific datasets to structural units and specifies the update frequency for each dataset. Many city councils also provide a link to their single electronic account on the Unified State Open Data Web Portal.

At the same time, there are problems with defining the formats in which local self-government data should be published. Few municipalities provide access to the document appointing the person(s) responsible for open data publication. But the biggest problem is the near-total absence of evidence that municipalities initiate or at least track the use of their data for building e-services capable of improving citizens’ lives.

As for open data publication, since 2022 the datasets of Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv have been removed by the state from public access, and among cities that do publish data there are still regional centers that have not switched to publication under the “single window” principle in the city council’s electronic account on data.gov.ua.

Of the 270 “EU integration” datasets that analysts searched for in 9 electronic accounts, 148 (55%) had been published as of December 5, 2025. Of these, only 51 datasets had timely updated resources. This result is largely due to the fact that Dnipro, Kropyvnytskyi, Lutsk, and Lviv city councils—leaders by number of published datasets—use their own open data portals, while the Ministry of Digital Transformation is unable to ensure regular monthly transfer of data from these portals to data.gov.ua.

Publication of timely updated datasets very rarely follows the interoperability principle. Analysis of timely updated datasets showed that only 6 of 51 datasets complied with all Ministry recommendations on unified object identifiers, unified dataset structures, and unified data resource structures.

The findings indicate a gap between indicators formed on the basis of local self-government self-assessment or aggregated national indicators, and the actual situation with open data publication and quality at the local level.

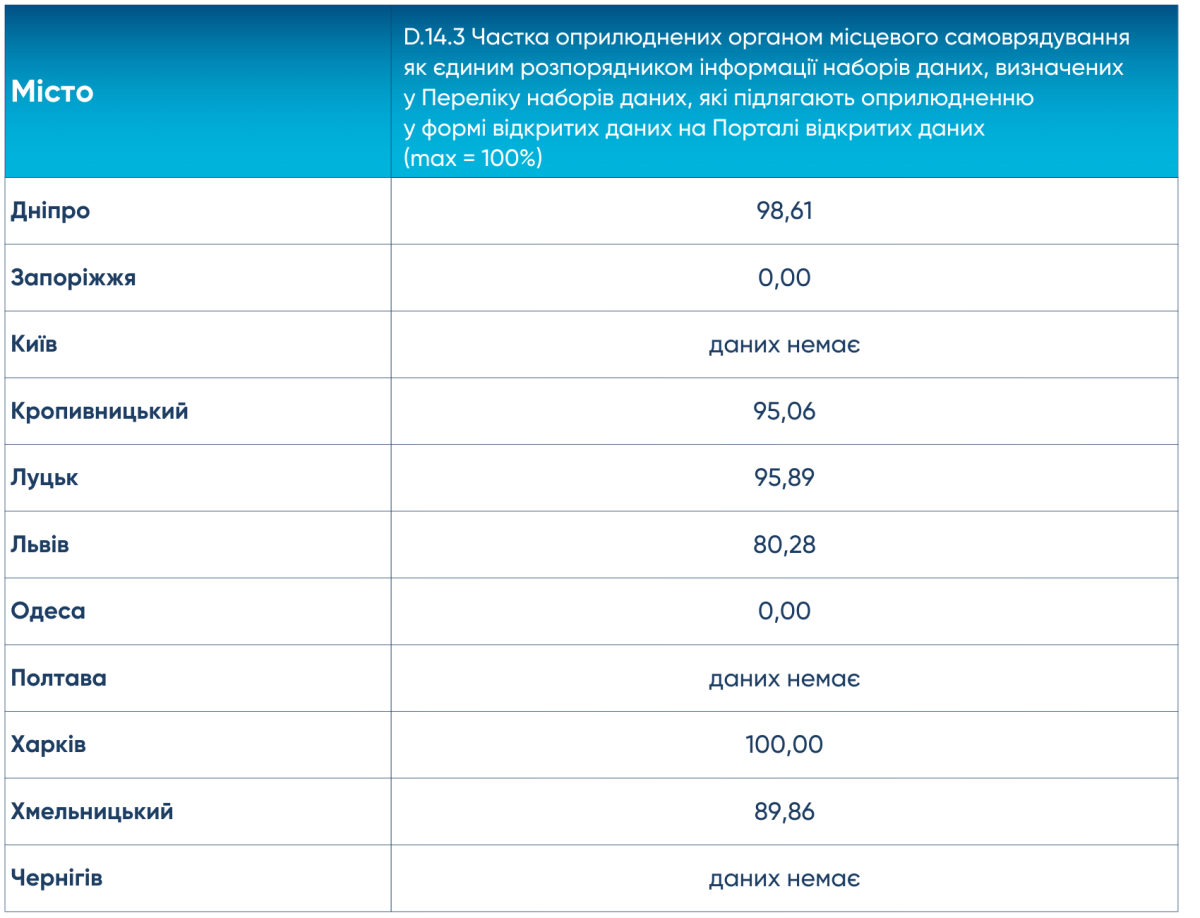

In particular, in the Digital Transformation Index of Ukraine’s territorial communities, Kharkiv reported publication of 100% of open datasets, Dnipro 99%, and Khmelnytskyi 90%; however, the verification conducted within this study did not confirm these figures. Similarly, Ukraine’s high position in the Open Data Maturity 2025 ranking (4th place, open data maturity level 97.1% compared with a European average of 81.1%) more likely reflects the existence of policies and initiatives at the national level than the real implementation of EU open data requirements in municipal practice.

Data from the Digital Transformation Index of Ukraine’s territorial communities on open data, as of January 11, 2026.

The program recommends that all cities (not only those included in the pilot sample) take into account the analytical findings, specifically:

- In line with the updated Resolution No. 835, approve a new internal administrative document containing the List of Datasets subject to publication in open data format. Taking into account the Ministry of Digital Transformation’s recommendations, specify for each dataset in the List:

- responsibility of specific information managers for preparation;

- responsibility of specific information managers for publication;

- update frequency (do not use the option “immediately after changes are made”);

- format (do not use labels that are not formats—excel, API, etc.).

- Create a dedicated open data section on the official city council website. In that section, provide links to:

- the document approving the Regulation/Procedure on open data;

- the document approving the current List of Datasets subject to publication in open data format;

- document(s) designating the person(s) responsible for open data publication;

- the decision on accession to the International Open Data Charter (if applicable);

- the city council’s single electronic account on the Unified State Open Data Web Portal.

- Compile information on services built on local self-government open data (maps, dashboards, chatbots, mobile apps) and provide links to these services in the dedicated open data section.

To ensure proper dataset publication on data.gov.ua, convenient access, and the ability to compare information both within a single dataset and across analogous datasets of other information managers, we recommend:

- Publish open datasets exclusively through the city council’s electronic account on data.gov.ua.

- Apply the practice of creating one city council dataset for each dataset established by Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 835, in line with European user-centric approaches.

- Check whether dataset titles in the city council account match the titles set out in Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 835.

- Conduct a detailed review of the Ministry of Digital Transformation’s dataset publication recommendations.

- Check whether the update frequency for each dataset, as specified in its file on data.gov.ua, matches the frequency in the approved List of Datasets.

- Prepare the number of resources recommended for each dataset. Resource structures (table fields) must fully match the recommended structures (see the table templates on the recommendation pages). Column names must be in English and fully replicate those proposed by the Ministry. There is no need to duplicate column names in Ukrainian. Abbreviating column names is unacceptable.

- Provide accurate and complete information in resources. If some data needed to fill cells are missing, the cells must be populated with null.

- Name resource files and resources themselves using the names recommended by the Ministry (e.g., regulatoryList_2026-06-01, titleList_2026-09-30).

- Publish resources only in the formats provided for in the approved List of Datasets (CSV/JSON/XML/GeoJSON). If resources are published in CSV format, use UTF-8 encoding with comma delimiters.

- Verify that each dataset page contains the number of resources recommended by the Ministry.

- Update resources forming datasets by version updates (see Example 1 and Example 2 of correct updates for datasets containing two resources each).

Since the Ministry of Digital Transformation is the lead body in the system of central executive authorities responsible for shaping and implementing state policy in open data, is the holder of the data.gov.ua portal, and supervises the portal administrator, the program recommends that the Ministry:

- Restore public access to those datasets of information holders from Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, Mykolaiv, Kharkiv, and Kherson regions whose publication does not pose a threat to national security, territorial integrity, or public order.

- Align, with the Ministry for Communities and Territories Development and the State Enterprise Administrator of the Urban Cadastre at the National Level, a unified position on access to municipal urban planning documentation during martial law, and publish it.

- Approve a three-year Open Data Development Strategy for Ukraine.

- Enshrine the “single window” principle in new versions of Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 835 or Resolution No. 867.

- Disseminate methodological guidance for information managers on transition to dataset publication under this principle. Pay particular attention to cases where, prior to applying the principle, multiple information managers within one council published identically named datasets either by exporting in open, machine-readable formats or by each providing their own API endpoint.

- Disseminate methodological guidance on resource updates via version updates.

- Disseminate methodological guidance on conducting an information audit.

- Clarify or remove inconsistencies in existing recommendations for open dataset publication, including:

- lists of legal and individual regulations (excluding internal ones), draft decisions subject to discussion, and the document designating the person(s) responsible for publishing open data;

- real-time data on the location of urban electric and passenger road transport;

- register of burial record books.

- Disseminate recommendations for the open dataset related to the unified public investment project portfolio of a territorial community, publication of which is required by Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 527.

- During moderation of municipal datasets, strictly enforce the “single window” principle so that structural units of local self-government bodies have no opportunity to publish data through their own separate accounts.

Establish regular monthly automated transfer of datasets from local open data portals to data.gov.ua. In case this technical issue cannot be resolved in the long term, officially notify the relevant local self-government bodies of the actions required from them under these circumstances.

The program will prepare tailored recommendations for each city council covered by the study, to serve as roadmaps for improving the practical operation of electronic services. The indicator-by-indicator results for each city are available at the link.

For cities not included in the pilot study, the program team has prepared a self-assessment form to evaluate compliance of the sector with European standards.

This research is made possible with the support of the MATRA Programme of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ukraine, and with the financial support of Sweden within the framework of the program on institutional development of Transparency International Ukraine. Content reflects the views of the author(s) and does not necessarily correspond with the position of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ukraine or the Government of Sweden.

Transparency International Ukraine is an accredited representative of Global Transparency International. Since 2012, TI Ukraine has been helping Ukraine grow stronger. The organization takes a comprehensive approach to the development and implementation of changes for reduction of corruption levels in certain areas.

TI Ukraine launched the Transparent Cities program in 2017. Its goal is to foster constructive and meaningful dialogue between citizens, local authorities, and the government to promote high-quality municipal governance, urban development, and effective reconstruction. In 2017–2022, the program annually compiled the Transparency Ranking of the 100 largest cities in Ukraine. After the full-scale invasion, the program conducted two adapted assessments on the state of municipal transparency during wartime. In 2024, the program compiled the Transparency Ranking of 100 Cities, and in 2025, it launched an updated format for assessing city councils — the European City Index.