The competition for selecting judges of the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC), which began in November 2023, can hardly be considered successful. As of March 2025, only two candidates for the first-instance court and none for the HACC Appeals Chamber have reached the final stage of the competition.

This was preceded by several stages of competitive selection. While disqualifying candidates during the competition is a normal process, the number of those who failed to meet the requirements for a HACC judge in this selection is striking. Accordingly, it became necessary to analyze the qualification exam procedures and the preceding stages in more detail.

This analytical note was prepared by TI Ukraine’s legal team. After a comprehensive analysis of the organization and conduct of the second competition for HACC judge positions, we identified systemic selection issues and provided recommendations for their resolution.

As part of this study, we conducted a detailed analysis of the following stages of the selection process: the announcement of the competition, the acceptance of documents, and the qualification exam. We focused particularly on the procedures for admitting candidates, appealing decisions on non-admission, organizing tests on law and cognitive abilities, and completing practical tasks.

Notably, this HACC judge competition was conducted with a modified procedure for certain stages of the qualification exam. Moreover, this occurred after a prolonged suspension of the HQCJ’s activities and alongside parallel selection procedures for other courts, which undoubtedly increased the HQCJ’s workload.

In this analytical note, we highlight the key issues of the competition to ensure they are considered in future selection processes. These problems include, but are not limited to:

- a limited pool of potential candidates due to specific legal requirements on length of service and restrictions on reapplying after a previous qualification assessment;

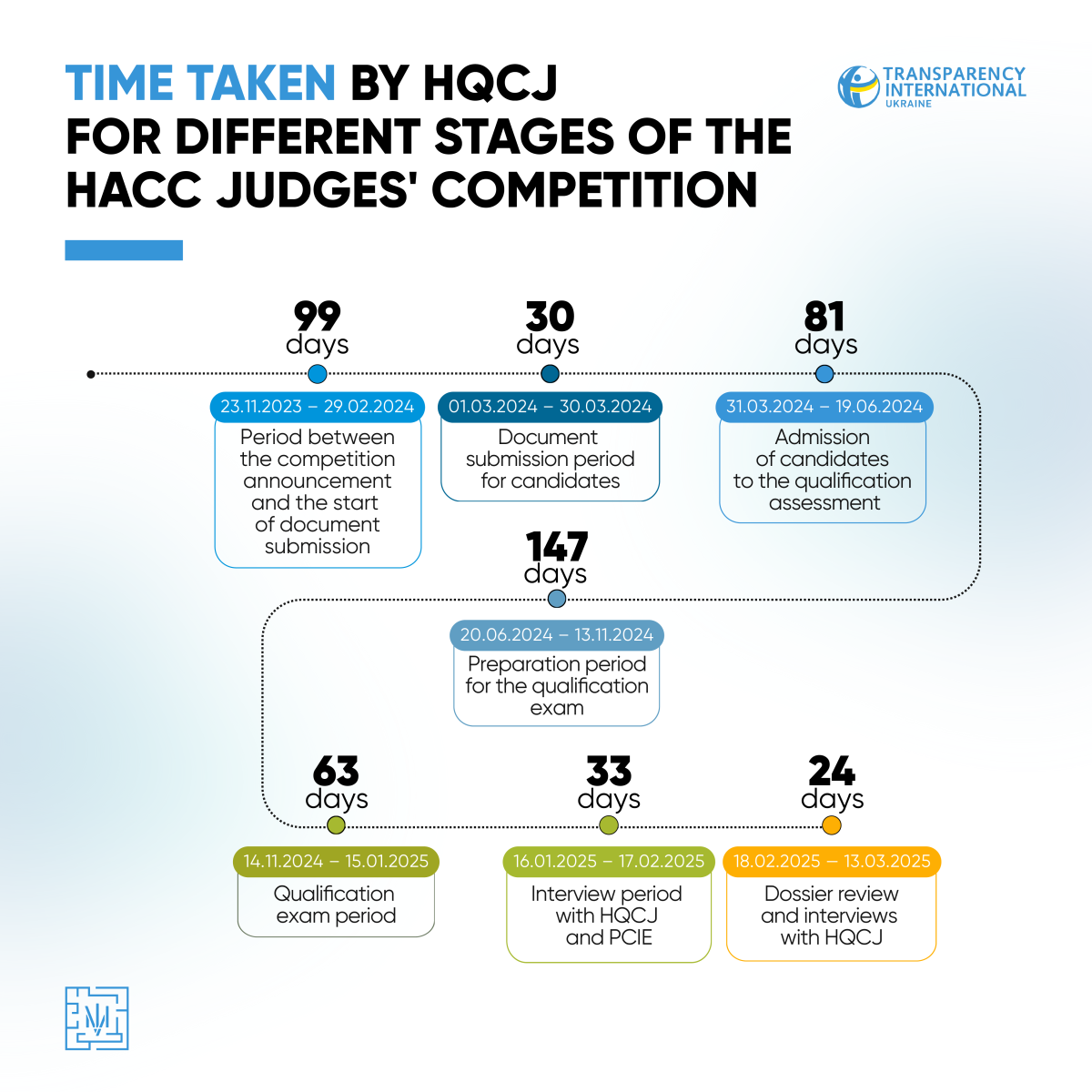

- an excessively long competition process (over 450 days) without a clearly published schedule;

- a short initial deadline for document submission, later extended, and the absence of adaptive conditions for military personnel regarding submission deadlines;

- errors in the legal test question database;

- an unreasonably high legally established threshold score for cognitive ability testing, resulting in the elimination of 64% of participants, without prior pilot testing considering the competition’s specifics;

- failure to publish the grading criteria for practical tasks and the completed works, limiting the transparency of the process.

The study is based on a comprehensive analysis of the regulatory framework, statistical data for each stage of the competition, HQCJ decisions, and interviews with select candidates and other stakeholders. All analysis results are supplemented with infographics that clearly illustrate candidate progress through the various stages of the competition.

In preparing this note, we aimed not only to identify problems but also to develop specific recommendations for improving the HACC judicial selection process, enhancing its transparency and effectiveness, and addressing future challenges in similar competitions.

The conclusions and recommendations in this document aim to strengthen the anti-corruption segment of Ukraine’s criminal justice system and enhance public confidence in the judiciary by upholding the highest standards in selecting judges for the Specialized Anti-Corruption Court. We have already shared all the collected materials with the High Qualification Commission of Judges of Ukraine.

In preparing this note, we aimed not only to identify problems but also to develop specific recommendations for improving the HACC judicial selection process, enhancing its transparency and effectiveness, and addressing future challenges in similar competitions.

Summary

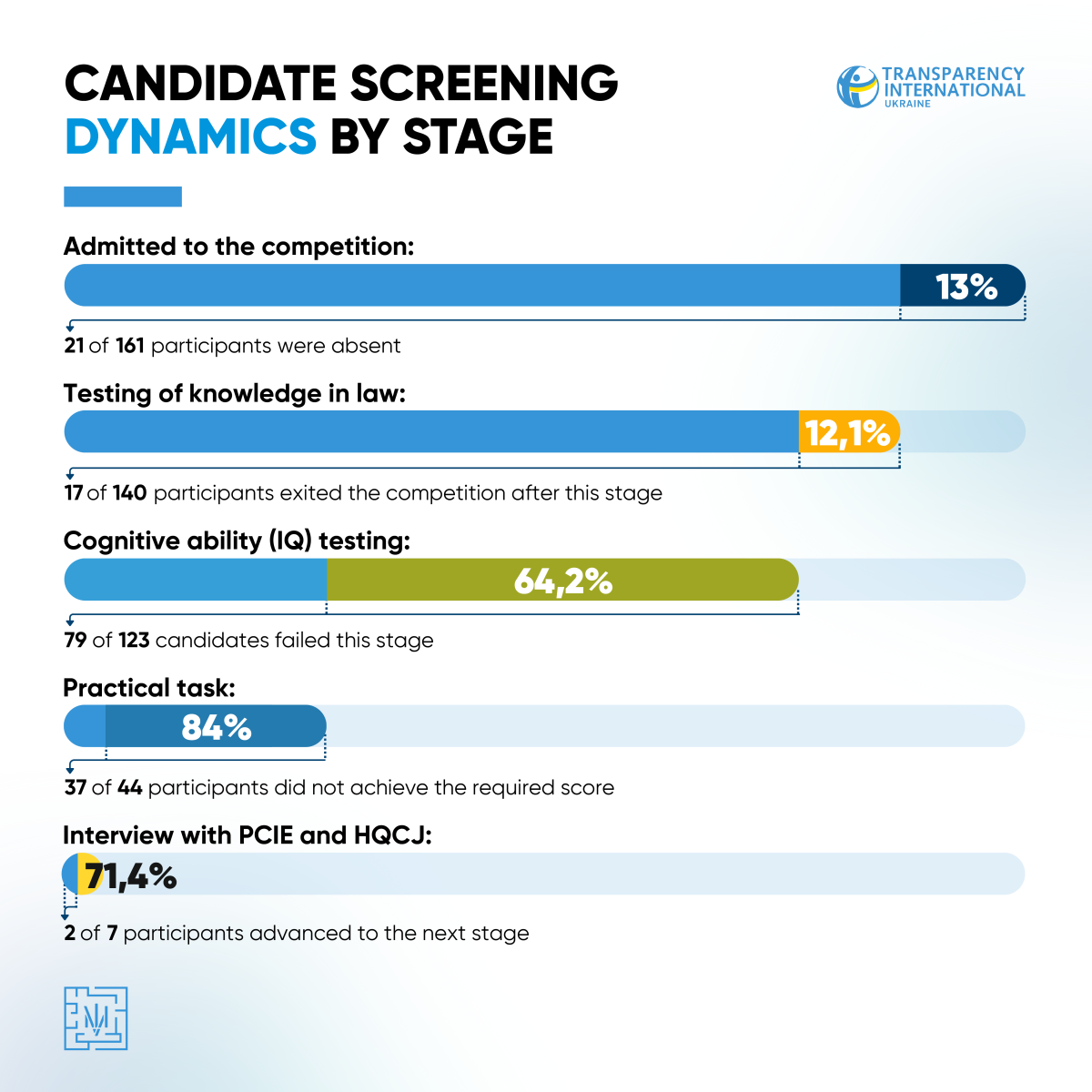

The second competition for judges of the High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine, announced in November 2023, aimed to fill 25 vacancies (15 in the first-instance court and 10 in the Appeals Chamber) in response to a critical increase in workload and the expansion of the court’s powers. The competition lasted more than 450 days. Of the 238 candidates who applied, only seven for the first-instance court successfully completed all stages of the qualification exam, while none did so for the Appeals Chamber. Only two candidates advanced to the interview stage with the HQCJ.

The outcome—only two finalists—reflects a series of issues that impacted the competition. Key factors contributing to this result included a limited pool of candidates due to specific legislative requirements, excessively long competition procedures without a clear schedule, short initial document submission deadlines without adaptation for military personnel, issues with the quality of legal test questions, an unreasonably high threshold score for cognitive ability testing, delayed parliamentary decisions to cancel the 75% threshold for IQ testing, and insufficient transparency in the Commission’s evaluation of practical tasks. As a result, despite the significant resources—time, money, and effort—spent on organizing and conducting the competition, the Commission fell far short of filling the 25 available vacancies.

However, this competition should not be considered entirely unsuccessful, as two candidates still reached the final stage, successfully navigating all selection procedures under these conditions. Amid a deep personnel crisis in the country, each new judge strengthens the HACC’s institutional capacity, making even this limited outcome a step forward.

Through our analysis, we identified key issues and proposed recommendations to address them.

- Specific length of service requirements restricts the pool of potential candidates. It is necessary to consider legislative changes to expand the pool of potential candidates by removing specific length of service requirements and lifting restrictions on the number of attempts to participate in the qualification assessment within a year.

- The prolonged duration of the competition without an early published schedule might lead to a loss of motivation among participants. While the need to develop test materials from scratch may have justified delays in the second HACC competition, further selections should establish and communicate a clear competition schedule in advance to help candidates plan accordingly.

- The short initial document submission deadline (15 days), later extended, restricted opportunities for candidates, particularly military personnel. Sufficient document submission deadlines should be established from the outset, with special provisions for military personnel.

- Errors in the legal test database forced participants to memorize incorrect answers. The legal test database should undergo additional quality checks, and legislative provisions should allow for administrative appeals and reviews of test results.

- The unreasonably high threshold score for cognitive testing led to the elimination of 64% of participants. Pilot testing should be considered to assess task complexity, the threshold score should be set using weighted approaches, and participants should receive clearer information about task types.

- Due to the lack of transparency in the assessment of practical tasks, the HQCJ disqualified 84% of participants. It is necessary to publish clear assessment criteria for each scoring category, disclose completed tasks along with scores, provide samples of top-scoring tasks, and ensure the high quality of practical task materials provided to competition participants.

Only systematic and high-quality efforts to address the identified problems will improve the chances of success in future competitions for selecting HACC judges, which will undoubtedly be held due to the unsatisfactory outcome of the second selection.

This selection process should be conducted without unnecessary delays to promptly fill all vacant positions at the HACC, especially given the growing activities of NABU and SAPO, which require a fully staffed judiciary. It is important to address these issues before the launch of new HACC competitions. This will contribute to the effective formation of the judicial corps and enable Ukraine to meet its international commitments in developing anti-corruption infrastructure.

Only systematic and high-quality efforts to address the identified problems will improve the chances of success in future competitions for selecting HACC judges, which will undoubtedly be held due to the unsatisfactory outcome of the second selection.

Background and results of the second HACC competition

The need to hold a second competition for positions at the High Anti-Corruption Court stems from multiple factors, including the critical workload of current judges and the expansion of the HACC’s powers.

The number of HACC judge positions, as determined by the decision of the HCJ, was set at 39: 27 judges for the first-instance court and 12 for the Appeals Chamber. The President of Ukraine appointed 38 judges by decree; however, the actual number of judges decreased in 2023. Subsequently, one first-instance judge was appointed as a member of the HQCJ and transferred to this body, reducing the actual number of first-instance judges to 26.

Since the establishment of the HACC in 2019, its workload has grown significantly each year. In addition to handling top-level corruption cases, the HACC’s jurisdiction was expanded to include civil cases on the recognition of unjustified assets and their recovery in favor of the state, as well as, since 2022, administrative cases on sanction-based asset recovery.

The insufficient number of judges, combined with the court’s expanded powers, has resulted in a critical increase in its workload. Between September 2019 and November 2024, the number of pending criminal cases before the HACC doubled, while the case review rate increased by 2.2 times. The statistics show a continuous accumulation of pending cases, increasing from 149 in 2019 to 287 in 2024.

The Ukraine Facility Plan for 2024–2027 provides that, by the first quarter of 2025, the full-time number of HACC judges will increase by 60 percent, and the court’s staff by 40 percent. In September 2023, by decision of the HCJ, the number of HACC judge positions was increased to 63, including 42 judges for the first-instance court and 21 for the Appeals Chamber.

To select judges, the HQCJ, by its Decision No. 145/zp-23 of November 23, 2023, announced a competition for 25 vacant positions—15 for the first-instance court and 10 for the Appeals Chamber.

The lengthy duration of the competition, which did not align with the plans of either the organizers or international partners, was one of the factors contributing to the significant gap between the approval of the number of judge positions and the actual staffing, posing a risk to the implementation of the Ukraine Facility Plan for 2024–2027.

The insufficient number of judges, combined with the court’s expanded powers, has resulted in a critical increase in its workload. Between September 2019 and November 2024, the number of pending criminal cases before the HACC doubled, while the case review rate increased by 2.2 times.

Requirements for HACC judges

Ukrainian legislation sets higher eligibility requirements for candidates applying for the position of a HACC judge. In particular, competition participants must meet the general judicial criteria, possess specialized knowledge, and have professional experience—either at least five years as a judge or at least seven years of academic or legal practice.

At the same time, individuals who have worked in law enforcement or other bodies specified in the HACC Law, held political positions, exercised a representative mandate, or were members of the governing bodies of political parties or certain state bodies prior to the implementation of reforms are not eligible to participate in the selection process.

Ukrainian legislation sets higher eligibility requirements for candidates applying for the position of a HACC judge.

Competition stages

The competition for the position of judge of the High Anti-Corruption Court is conducted in accordance with the special procedure established by the Law of Ukraine on the Judiciary and the Status of Judges, taking into account the provisions of the Law of Ukraine on the High Anti-Corruption Court. The competition includes the following stages.

- Submission of documents — individuals wishing to participate in the competition may submit an application and documents confirming their compliance with the eligibility requirements for the position of judge via the candidate’s electronic account on the official HQCJ website.

- Verification of submitted documents by the HQCJ — review of candidates’ compliance with formal requirements and their admission to the qualification assessment.

- Anonymous testing — includes assessments of legal knowledge, the history of Ukrainian statehood (not conducted in this selection), and cognitive abilities (IQ test).

- Practical task — completion of a specialized assignment to assess professional skills in drafting court decisions.

- Special check — verification of the information provided by the candidate based on data received by the HQCJ from official sources.

- Joint interview with the HQCJ and PCIE — conducted if deemed necessary by the PCIE, this evaluation stage involves the Public Council of International Experts, whose members have a decisive vote on the candidate’s compliance with integrity and professionalism criteria.

- Interview and review of candidates’ dossiers — the HQCJ reviews information about the candidate to preliminarily assess their compliance with judicial criteria and conducts an interview based on the dossier findings.

- Final interview with the winners — the HQCJ’s final assessment of candidates who have successfully completed all previous stages.

- Issuing a recommendation by the HQCJ in a plenary session.

- Consideration of the HQCJ’s recommendations by the HCJ — the High Council of Justice decides whether to submit or refuse to submit a motion to the President of Ukraine for the appointment of candidates to judicial positions.

- The appointment of judges by the President of Ukraine is the final stage of the competition.

The key features of the HACC competition are:

- increased transparency requirements — all stages of the qualification assessment are recorded on video and audio, with real-time broadcasting;

- prohibition on the transfer of judges from other courts without a competitive selection process;

- A special procedure for a joint meeting of the HQCJ and the PCIE, during which decisions are made by a majority of the joint composition, provided that at least half of the PCIE members support the decision.

The key features of the HACC competition are increased transparency requirements, prohibition on the transfer of judges from other courts without a competitive selection process, a special procedure for a joint meeting of the HQCJ and the PCIE.

Intermediate results of the competition

The second competition for HACC judge positions, announced in November 2023, was characterized by a high rate of candidate disqualification at all stages of the selection process.

A total of 238 individuals submitted documents to participate in the competition, of whom 161 were admitted to the competition procedures. A total of 140 participants attended the first stage of testing.

As a result of the competitive selection, only 5% of participants who took part in the qualification exam advanced to the next stage—dossier review and interviews. 95% of candidates failed the test and practical task stages.

Of the 44 candidates who reached the practical task stage, only seven applicants for the first-instance court of the HACC were able to surpass the established threshold of 112.5 points. None of the candidates for the position of judge of the HACC Appeals Chamber scored the required number of points.

This outcome means that, out of 140 candidates who began participating in the competition, only one in twenty successfully passed the entire exam and advanced to the interview stage, reflecting the strict requirements and high selection standards for HACC judge positions.

The competitive selection of judges should primarily focus on the quality of candidates rather than solely on the goal of filling all vacant positions. However, such strict screening was one of the reasons for the insufficient number of candidates to fill all the announced vacancies, particularly in the HACC Appeals Chamber, creating additional challenges for ensuring the court’s effective operation and implementing plans to expand its staff.

On January 23, the HQCJ announced the launch of a new competition for positions in the HACC Appeals Chamber. TI Ukraine considers this decision hasty, as the list of problems outlined in this analytical note was already evident at the time the competition was announced. Draft Law No. 13114, which could address certain shortcomings, is currently registered in parliament.

As a result of the competitive selection, only 5% of participants who took part in the qualification exam advanced to the next stage—dossier review and interviews. 95% of candidates failed the test and practical task stages.

Problems that could have prevented the high-quality selection of HACC judges

The competition for the selection of HACC judges, which began at the end of 2023, can hardly be considered successful, given its outcomes. In the course of our analysis, we identified problems that arose at various stages of the judge selection process and proposed options for addressing them.

The period between the announcement of the competition and the start of the qualification exam

Timeframes and scheduling of competition procedures

On November 23, 2023, the HQCJ announced the start of the competition for HACC judge positions, and nearly one year passed before the first tests were conducted. During this period, the Commission accepted applications from individuals wishing to participate in the competition and granted them admission to the qualification assessment. However, a reasonable question arises: did these actions truly require such a lengthy period?

Before the one-year anniversary of the launch of the second HACC judge selection, we had already pointed out that the competition procedures were taking too long, despite the Commission’s efforts to approach their implementation thoroughly.

As a result, although the competition procedures had certain schedules, they were not always adhered to. Before accepting documents, the Commission predicted that it would complete the competition and issue recommendations by the end of 2024; however, in October 2024, this deadline was postponed to May 2025. It is clear that the development of task databases, as well as assessment procedures and methodologies in line with the new legislation adopted in December 2023, required significant time. However, this does not change the fact that the Commission did not issue any other official public communications regarding the timelines of the competition procedures.

As of the date of the announcement of the qualification assessment results, the competition has been ongoing for 477 days. The Commission used this time as we describe below.

At the same time, it should be noted that the new composition of the HQCJ resumed the competitive selection for the HACC after a prolonged suspension of its activities. In addition to the HACC competition, the Commission also organized other selection procedures for appellate courts, completed the competitive procedures for local court judge positions initiated in 2017, and arranged the development of a test database for participants. This undoubtedly affected the workload of the Commission members.

Under these circumstances, it is difficult to speak of the timely fulfillment of obligations under the Ukraine Facility Plan. In addition, even a justified delay in the competition could negatively impact some participants’ motivation to continue in the selection process, as most of them are practicing lawyers, judges, or scholars with existing obligations to clients and employers. The absence—primarily due to objective reasons—of a published schedule for the competition procedures, along with the Commission’s failure to meet its indicative forecasts, significantly complicated applicants’ participation in the selection process, preventing them from properly planning their professional activities or taking leave to prepare for and participate in the competition.

It can be assumed that this was one of the reasons why 21 out of the 161 admitted participants (13%) did not appear for the first test and withdrew from the competition.

Thus, it can be concluded that the duration of the competition procedures exceeded even the HQCJ’s own expectations. This had a negative impact on the fulfillment of international obligations and may have affected the motivation of competition participants.

Therefore, to improve the situation, the HQCJ should publish the competition calendar in advance, enabling candidates to plan and coordinate their participation in the competition procedures.

Even a justified delay in the competition could negatively impact some participants’ motivation to continue in the selection process, as most of them are practicing lawyers, judges, or scholars with existing obligations to clients and employers.

Acceptance of documents

The collection of documents through the electronic account on the HQCJ website began on March 1, 2024, and was initially scheduled to last 15 days. The Commission assumed that a sufficient number of lawyers would apply within this period; however, shortly before the deadline, it became clear that only 104 applicants had contacted the HQCJ. To address this situation, the submission period was extended to 30 days, until March 30.

This decision by the HQCJ had a positive impact on the pool of participants, increasing the number of applicants to 238.

However, it can be assumed that the number of participants could have been higher if the Commission had initially set a longer deadline for document submission and had provided additional time specifically for military personnel to submit their documents. It should be emphasized that the deadline for submitting documents must allow sufficient time for all applicants, from the very first day, to collect and submit all the required documents to the HQCJ.

A predetermined, sufficiently long period for submitting documents also ensures that potential candidates have enough time to calculate and verify their professional experience. For example, a candidate assessing the deadlines set by the HQCJ for submitting documents should be able to determine whether they have sufficient professional experience and, if not, decide not to prepare for participation. After the deadlines were extended, some candidates who did meet the experience requirements may no longer have had enough time to collect and submit the necessary documents. Although minor, these factors could also have influenced the number of individuals who applied to the HQCJ to participate in the competition.

For future competitions, it will be equally important to encourage the participation of active military personnel during the period of martial law. This category of potential participants does not always have the physical ability to collect and submit all the necessary documents on time, due to their involvement in measures to repel armed aggression against Ukraine. Therefore, in this context, it would be reasonable to grant military personnel additional time to apply to the HQCJ for participation in the HACC competition. This will ensure equal opportunities for all those who wish to become HACC judges and will also help increase the number of participants.

Notably, the Commission applied a similar approach in the selection of local judges, where the deadline for military personnel to submit documents was doubled.

In the context of a serious human resources crisis in the judiciary, it should be recognized that not only judges, lawyers, and scholars may meet the eligibility requirements for HACC judge positions. Expanding the number of individuals interested in becoming HACC judges will improve the quality of the candidate pool; therefore, it is advisable to consider broadening the list of eligible applicants for the next HACC competition. The Commission has already taken initial steps in this direction by appealing to the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Legal Policy with a proposal to reduce the restriction period for former law enforcement officers to participate in the competition from ten to five years.

Also, at least during martial law, it is necessary to consider lifting the legislative ban set out in Articles 74 and 84 of the Law of Ukraine on the Judiciary and the Status of Judges, which prohibits candidates from applying for a new competition in the same court and instance if they have already participated in a qualification assessment for the same position within the past year. The HQCJ has also developed and submitted a relevant proposal to parliament.

As a result, MPs registered Draft Law No. 13114, amending the procedure for additional selection of HACC judges:

- removal or relaxation of restrictions for employees of certain bodies regarding their eligibility to participate in the competition for the position of a HACC judge;

- suspension, for the duration of martial law and one year thereafter, of the rule restricting participation in the competition for candidates who failed to appear, refused to take, or did not pass the qualification exam;

- the law eliminates the requirement for candidates to score at least 75% of the maximum points on the test on the history of Ukrainian statehood.

Accordingly, the following conclusions and recommendations can be drawn in this section.

The process of accepting documents for participation in the competition has advanced to a new level thanks to the digitalization of this procedure. At the same time we assume that the number of potential candidates could have been higher if the Commission had set sufficient deadlines for submitting documents in advance, and also adapted this process taking into account the context of participation in the selection of military personnel. Additionally, increasing the number of participants will help expand the pool of individuals eligible to become HACC judges.

Therefore, to improve the situation, the HQCJ should:

- encourage lawyers to apply for the new HACC competition, particularly by explaining how it differs from the previous competition and by taking into account the lessons learned;

- set realistic deadlines for document submission and extend the submission period for military personnel.

The legal community and MPs should discuss the possibility of expanding the pool of potential candidates for the HACC competition by removing the requirements for specific length of service (as a judge, lawyer, or scholar).

The parliament must promptly improve the procedure for the competitive selection of HACC judges by adopting the improved legislation, as any delay negatively affects both the fulfillment of international obligations and the overall effectiveness of the court.

It can be assumed that the number of participants could have been higher if the Commission had initially set a longer deadline for document submission and had provided additional time specifically for military personnel to submit their documents.

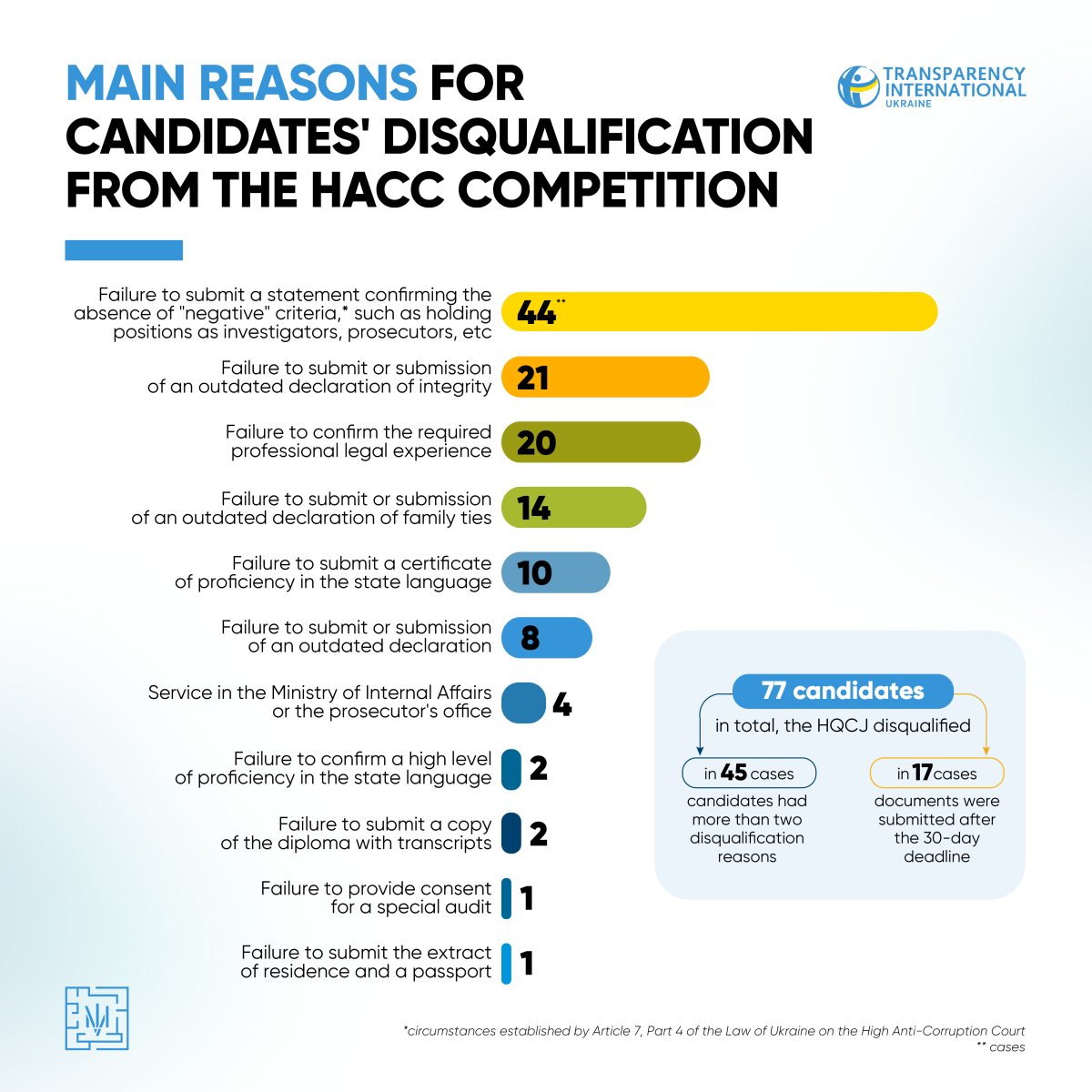

Admission to the qualification assessment

The HQCJ considered the admission of candidates to the qualification assessment between March 31 and June 19, 2024. During this period, the Commission held 7 meetings and admitted 161 out of 238 applicants (67%) to the qualification assessment.

Only those applicants who submitted a complete set of documents on time and confirmed their required legal experience were admitted to the assessment. According to our estimates, 77 candidates did not meet these conditions, and the reasons for their non-admission were as follows:

- failure to submit a declaration confirming the absence of circumstances specified in Article 7, Part 4 of the Law of Ukraine on the High Anti-Corruption Court (the so-called “negative” criteria, such as not having held positions of investigator, prosecutor, etc.);

- failure to submit or submission of an outdated declaration of integrity;

- failure to confirm the required professional legal experience;

- failure to submit or submission of an outdated declaration of family ties;

- failure to submit a certificate of proficiency in the state language;

- failure to submit or submission of an outdated declaration of property;

- service in the bodies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs or the prosecutor’s office;

- failure to confirm a high level of proficiency in the state language;

- failure to submit a copy of the diploma with transcripts;

- failure to provide consent for a special audit;

- failure to submit the extract of residence and a passport.

In 45 cases, there were more than two grounds for non-admission, and in 17 cases, the documents were submitted after the designated thirty-day period.

Among those who were not admitted to the competition, nine individuals appealed these decisions to the HQCJ in a plenary session; however, the Commission rejected all of their appeals. It is noteworthy that, in one of its decisions, the Commission acknowledged the valid reasons why a candidate who was a serviceman failed to submit all the required documents; however, since the submission deadline had passed, the candidate was still unable to continue participating in the competition. This example confirms the issue of timely document submission by military personnel, as described in the previous section, and highlights the need to extend the submission period for this category of applicants.

One of the candidates who failed to confirm the required professional experience also attempted to appeal the HQCJ’s decision in the Cassation Administrative Court; however, the court ruled in favor of the Commission. The court clarified that it is the responsibility of the candidate to provide all necessary evidence confirming their professional experience.

The most common mistakes in applicants’ document submissions included failing to provide statements confirming the absence of circumstances outlined in Article 7, Part 4 of the Law of Ukraine on the High Anti-Corruption Court, failing to submit integrity declarations or submitting outdated ones, and failing to submit family ties declarations or submitting outdated versions.

The reality is that many HACC competitors were simultaneously participating in the competition for appellate court judge positions, with the document submission process for those roles having started in 2023. Of the 44 competitors excluded from the HACC competition due to the absence of a corresponding application, 33 had submitted documents for participation in the appellate courts competition. This application is a requirement unique to the HACC judge competition. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that these candidates had not fully updated their documentation specifically for this competition.

A similar assumption applies to the submission of outdated integrity declarations, family ties declarations, and property declarations—HACC competitors frequently submitted last year’s declarations, likely prepared specifically for the appellate court competition in December 2023.

Another common reason for refusal was the lack of the required legal experience (length of service). In most cases (19 out of 20), this confirmation was required from lawyers, who needed to provide at least one court decision or another document proving they had represented or defended clients.

At this stage, it became clear that the primary cause of document submission problems was participant errors—either a lack of sufficient experience (length of service) or a lack of attention to detail when submitting their documents.

Thus, the following recommendation can be formulated: prospective participants in the HACC competition must exercise care and thoroughness when submitting the required documentation, taking into account the specific requirements of the competition. Additionally, the Commission could analyze the most common mistakes made by users of the web resource and improve the platform’s interface accordingly.

The most common mistakes in applicants’ document submissions included failing to provide statements confirming the absence of circumstances outlined in Article 7, Part 4 of the Law of Ukraine on the High Anti-Corruption Court, failing to submit integrity declarations or submitting outdated ones, and failing to submit family ties declarations or submitting outdated versions.

Stage of the qualification exam

The law test

The law test was the first stage of testing for the competitors, and the vast majority successfully completed it. Out of 140 participants, 123 passed the 75% threshold and advanced to the cognitive aptitude test. Meanwhile, 21 individuals who had been admitted to the assessment failed to attend and subsequently dropped out of the competition.

To assist competitors with their preparation, the Commission published a test database with correct answers in advance. According to the National School of Judges, over 4,200 tests were created for the High Anti-Corruption Court and its Appeals Chamber competitions, including 1,225 developed with the input of external experts. However, concerns were raised about the quality of this database by both the test reviewers and the participants themselves.

Some questions contained incorrect answers, prompting the HQCJ to remove them from the list on two occasions, November 6 and November 13, 2024—a total of 76 questions were excluded. However, despite these removals, interviews with participants revealed that the database still contained additional flawed questions that were not removed and appeared during the testing.

This forced participants to memorize incorrect answers so as not to lose points. Since it was impossible to contest these flawed results, memorizing incorrect answers became the only way for competitors to successfully pass this stage.

The HQCJ’s new approach of publishing correct answers alongside the questions seems logical in terms of providing equal conditions for participants. However, it created a new problem: participants intentionally giving incorrect answers to earn points.

A possible solution to this issue is to grant participants the right to contest their results when the correct answers are found to be incorrect. To avoid overburdening the Commission, complaints concerning the same issues could be consolidated into a single case.

Accordingly, the following conclusions and recommendations can be drawn in this section.

The legal testing phase did not encounter significant organizational issues. However, the presence of errors in the test database forced candidates to memorize and provide deliberately incorrect answers in order to score points. This issue can be addressed by allowing participants to challenge the incorrect inclusion of a wrong answer in the test database as correct.

To address this issue, the HQCJ should organize a thorough review of the legal test tasks to minimize errors.

The parliament should consider allowing candidates to challenge (review) the results of legal tests, similar to how admission refusals are handled, but without providing a pathway for court appeals.

Some questions contained incorrect answers, prompting the HQCJ to remove them from the list on two occasions, November 6 and November 13, 2024—a total of 76 questions were excluded. However, despite these removals, interviews with participants revealed that the database still contained additional flawed questions that were not removed and appeared during the testing.

Cognitive testing

This stage proved to be one of the most contentious in the competition, as it led to the elimination of 79 out of 123 participants—64.2% of all those who reached this phase. For comparison, similar testing in the competition for appellate court judge positions disqualified only 468 out of 1,588 participants, or 29.5%.

The elimination of more than half the participants resulted in fewer than two candidates per available position, significantly reducing the quality of the candidate pool for the Commission.

The introduction of this type of testing as a mandatory component occurred in December 2023 under the Law on Improving the Procedures for Judicial Careers. Previously, such tests, for instance, in competitions for the Supreme Court or the High Court on Intellectual Property, were used as supplementary rather than primary measures. During discussions about changing the procedure for setting the threshold score, concerns were raised that transferring this authority to the HQCJ could pose a risk—namely, that the score might be manually lowered to ensure the success of certain candidates. As a result, when introducing the static threshold score of 75%, legislators failed to consider the unique aspects of cognitive ability assessments.

IQ testing is not a standard test where the results depend solely on a candidate’s preparation and memory. Scientific studies have shown that accurately measuring human intelligence is quite challenging. Consequently, administering such tests as part of competitive procedures for judicial positions should account for a margin of error in the assessment’s precision.

On November 11, 2024, parliament passed a law permitting the Commission to lower the threshold score for this testing to a more “reasonable” level. However, this provision was never applied to the HACC competition because it had not yet taken effect by the testing date (December 4, 2024), and its transitional provisions stated that the new law would apply to the appellate court competition. The regulatory act itself did not mention any non-application of these rules to the HACC competition.

As a result of these inconsistent actions, the excessively high 75% threshold prevented 79 participants, including several highly professional and virtuous scholars and practitioners, from advancing to the next stages of the HACC competition.

Currently, the provision allowing for a lower threshold score will apply to future HACC competitions. However, at the time this law was adopted, we had already highlighted the need to define clear criteria for the HQCJ to use in setting the threshold score for cognitive ability tests. These criteria should ensure that the assessment of candidates’ cognitive abilities is neither unjustifiably lowered nor excessively raised. Additionally, pilot testing should be conducted to identify potential shortcomings.

The high threshold score is not the sole reason for the disappointing results in the cognitive ability assessment; the quality of the questions themselves also played a significant role. Respondents reported that the tests made available by the Commission before the exam only covered the first and second levels of difficulty, rather than all four. As a result, many candidates were surprised to find that the exam tasks were significantly more challenging than those provided for review. The lack of clear guidelines for preparation further heightened participants’ anxiety both before and during the test.

Interestingly, the quality and reliability of the IQ test database were supposedly ensured by the company that developed the Psymetrics tool. However, no clear information is available about any pilot testing conducted by the HQCJ to verify the provided database. This was confirmed by HQCJ member Serhii Chumak in comments on a post discussing the IQ test results from the HACC competition, where he stated that “the HACC testing essentially became that pilot testing.”

Using these tasks to assess contestants’ intelligence levels in the HACC competition made this stage a critical determinant for the entire process. For instance, during the 2017 Supreme Court competition, the HQCJ had an unapproved database for the law test and did not establish a passing score in advance.

Undoubtedly, the experience gained from conducting the IQ assessment in the HACC competition helped incorporate lessons learned and improve the process for the appellate courts’ competition, where less than a third of the candidates were disqualified.

This is also evidenced by the fact that a significant portion of candidates who participated in both competitions (the appellate court competition and the HACC competition) achieved noticeably higher IQ test scores in the appellate court competition than in the HACC selection process. This discrepancy could also be attributed to participants in the competitive procedures sharing their experiences with one another.

Accordingly, the following conclusions and recommendations can be drawn in this section.

The threshold test score of 75% was unwarranted and failed to consider the specific nature of IQ testing. When combined with overly challenging and occasionally flawed tasks, this resulted in nearly 65% of participants being disqualified—an outcome that is far from ideal.

To improve the situation, the HQCJ should:

- conduct pilot IQ testing to pre-assess its complexity and determine its suitability for use in the qualification assessment of judicial candidates;

- standardize the process for determining the threshold score by applying balanced methods and drawing on previous experience with competitive procedures;

- consider providing participants with more comprehensive information about the types of tasks and guidance on how to prepare for them.

This stage proved to be one of the most contentious in the competition, as it led to the elimination of 79 out of 123 participants—64.2% of all those who reached this phase. For comparison, similar testing in the competition for appellate court judge positions disqualified only 468 out of 1,588 participants, or 29.5%.

Practical task

A significant percentage of participants were unable to successfully complete the practical task. Out of 44 participants, 37—84%—were disqualified from the competition due to receiving unsatisfactory scores on this assignment. Only seven candidates for first-instance judgeships at the HACC managed to pass this stage, while none of the candidates for the HACC Appeals Chamber succeeded.

On December 16, 2024, 44 participants of the HACC competition completed practical tasks; however, neither the public nor the participants were informed about the specific criteria used to evaluate these tasks.

The practical task is one of the most important stages of the qualification assessment, as it demonstrates participants’ ability to make and justify decisions in cases they may potentially adjudicate. However, the results of the practical task in the HACC competition indicate that certain aspects of the assessment system were problematic, preventing a significant number of candidates from advancing to the interview stage.

The practical tasks were evaluated by an Examination Commission established under the qualification exam procedure, consisting of three HQCJ members and three independent experts appointed with donor support—an approach intended to enhance the objectivity of the assessment.

As a general rule, participants’ practical tasks should be evaluated based on the previously published Methodological Recommendations for assessing such tasks, with a maximum score of 150 points. The recommendations advise examiners to assess the quality and completeness of legal qualifications, the analysis of evidence, the conclusions drawn from the case review, as well as the logic, coherence, and clarity of the court decision.

The introduction of these Methodological Recommendations was one of the key public demands during the first competition for HACC judge positions. However, the partial implementation of this requirement clearly did not enhance the transparency and objectivity of this stage of the exam. The HQCJ did not publish the completed practical tasks, the results of the anonymous and roll-call evaluations of participants’ work, or the specific assessment forms. Although the Methodological Recommendations introduced evaluation criteria, it is worth noting that such recommendations were developed and published for the first time.

The Law on Improving the Procedures for Judicial Careers, adopted in December 2023, established that competition participants must receive 50% of the qualification assessment points for the qualification exam — a measure intended to enhance the objectivity of the evaluation.

In this regard, we requested the HQCJ to provide the results of the anonymous assessment of the participants’ practical tasks. However, in response to our request, the Commission stated that it does not maintain records of forms or questionnaires used to record scores based on the indicators set out in the Methodological Recommendations for evaluating practical tasks. This lack of documentation undoubtedly grants excessively broad discretion in the evaluation process.

A participant in our survey also noted that the Methodological Recommendations contain numerous evaluation criteria that examiners could interpret at their own discretion. Some respondents suspected that the Examination Commission did not apply the stated Methodological Recommendations and instead used a different evaluation approach.

Some of the respondents we interviewed also disagreed with the scores they received and believed that the evaluation of their work was highly subjective. One of the participants even submitted a request to the Commission for the results of the assessment of their work but did not receive either the roll-call or criteria-based evaluation. Importantly, the response revealed that the participant’s work was scored at 84, 71, 90, 69, 68, and 68 points, with an average score of 75 and a difference of up to 22 points between examiners’ assessments. The candidate could have received a maximum of 150 points.

The results of this stage of the qualification exam also prompted candidates to request examples of “ideal” answers to the practical task, which would qualify for the maximum score. This suggestion stems from the need to understand how to achieve the highest score when resolving a court case and drafting a court decision. Such materials are available to the National School of Judges, which is responsible for developing the task databases for the qualification exam. However, different people may have varying views on what constitutes an “ideal” judgment.

Clearly, the efforts to ensure an objective assessment during the HACC competition did not yield significant results, as the evaluation of the practical task lacked adequate transparency mechanisms, ultimately undermining confidence in its objectivity.

We also requested the HQCJ to provide the completed practical tasks along with the detailed assessment forms. The Commission stated that access to the notebooks containing practical tasks is restricted to protect the reputation and rights of competition participants, as disclosing this information could significantly harm these interests. According to the HQCJ, the potential negative consequences of disclosing this information significantly outweigh the public interest in accessing it.

It is worth noting that, by applying for the competition, participants should already be prepared for the fact that, if appointed as judges, the court decisions they issue will be public and subject to detailed analysis by all interested parties.

This is also supported by some of the respondents we interviewed, who, on the contrary, expressed no objection to the publication of their practical tasks, as was the case during the competition for the positions of disciplinary inspectors of the HCJ.

The Commission’s failure to publish participants’ practical tasks and to maintain records of the anonymous assessment prevents confirmation of the claim that the evaluation process was sufficiently objective. These “unimpressive” results required — and still require — explanation, and the lack of transparency undermines confidence in the outcomes not only among the public but also among the participants of the HACC competition.

Undoubtedly, some participants did not produce high-quality work; however, our survey indicated that the quality and volume of materials provided to participants for the practical task may have also influenced the results. Participants in this stage of the exam identified technical and logical errors in the materials provided, which at times made it difficult to complete the task. The absence of Supreme Court positions among the supplementary materials further distanced the test conditions from the real circumstances of case resolution and court decision writing.

Some respondents expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that the additional materials were available exclusively in electronic form and that it was impossible to perform an end-to-end search of the regulatory and other documents (such as codes, ECHR decisions, etc.) provided to applicants for the position of HACC first-instance judge.

Accordingly, the following conclusions and recommendations can be drawn in this section.

The results of the practical task in the HACC competition ultimately prevented the filling of all 25 vacant judge positions. The disqualification of 84% of participants at this stage appears excessive, and the lack of transparency in the assessment system undermines confidence in the results of this stage of the exam.

To improve the situation, the HQCJ should:

- approve standardized forms or questionnaires that examiners must use to evaluate the completed tasks, assigning scores and providing justification for each criterion outlined in the Methodological Recommendations;

- publish the completed practical tasks along with the corresponding evaluation forms or questionnaires completed by the examiners;

- publish sample answers to practical tasks that received maximum scores;

- expand the range of materials provided to competition participants to include decisions of the Grand Chamber or joint chambers of the Supreme Court;

- conduct a preliminary quality check of the model case materials to identify and correct technical errors in the procedural documents, and extend the time allotted for completing the task.

The HQCJ did not publish the completed practical tasks, the results of the anonymous and roll-call evaluations of participants’ work, or the specific assessment forms. Although the Methodological Recommendations introduced evaluation criteria, it is worth noting that such recommendations were developed and published for the first time.

Challenges of the third HACC competition

On January 23, 2025, the HQCJ announced the launch of a new competition for positions in the HACC Appeals Chamber, as the second competition failed to fill any of the vacant positions in this body. Therefore, we anticipate the announcement of another competition for the first-instance positions at the High Anti-Corruption Court in the near future. Ideally, the Commission plans to conduct both competitions in parallel, allowing participants to apply for judge positions in both instances.

In addition to the issues outlined above, these upcoming competitions will also face new challenges, including:

- an unjustifiably high threshold score of 75% for the test on the history of Ukrainian statehood;

- encouraging lawyers to participate in these selections through a high-quality information campaign.

The Commission is aware of these challenges and has already submitted proposals for legislative changes regarding the unreasonably high threshold score for the history of Ukrainian statehood test. In addition, an information campaign is planned to highlight the key advantages of the new competitions, emphasize how they differ from previous selections, and thereby encourage more professionals to apply.

On March 31, 2025, the HQCJ postponed the previously set deadline for submitting documents for the selection of judges of the HACC Appeals Chamber, moving it from April 1 to June 1, thereby delaying the start of the competition procedures. The Commission expects that, during this period, Parliament will be able to review and adopt Draft Law No. 13114, which would ease the passing score requirements for non-core tests and allow a broader range of lawyers to participate in the competition. Also, postponing the start date for document submission may help synchronize the competitive selection processes for judges of both the Appeals Chamber and the first-instance court of the HACC.

The Commission is aware of these challenges and has already submitted proposals for legislative changes regarding the unreasonably high threshold score for the history of Ukrainian statehood test. In addition, an information campaign is planned to highlight the key advantages of the new competitions.

Potential improvements in legislative framework of the procedure

As we have already noted, on March 18, 2025, the parliament registered Draft Law No. 13114. It includes several proposals that, if adopted, will have a significant impact on the HACC competition:

- removal or relaxation of restrictions for employees of certain bodies regarding their eligibility to participate in the competition for the position of a HACC judge;

- suspension, for the duration of martial law and one year thereafter, of the rule restricting participation in the competition for candidates who failed to appear, refused to take, or did not pass the qualification exam within the year;

- the law eliminates the requirement for candidates to score at least 75% of the maximum points on the test on the history of Ukrainian statehood.

The first proposal is aimed at expanding the pool of potential candidates. In particular, the MPs propose to remove from the list of ineligible candidates those who have held positions in bodies indirectly related to the criminal process for 10 years, such as officials of the Anti-Monopoly Committee of Ukraine, the Accounting Chamber, central bodies of the tax and customs services, and anti-corruption bodies like the NACP and ARMA.

It is also proposed to reduce from ten to five years the period during which individuals who held positions in bodies involved in criminal investigations—such as the Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine (except SAPO), internal affairs bodies, the State Bureau of Investigation, the Security Service of Ukraine, or the Bureau of Economic Security of Ukraine—are prohibited from participating in the competition. At the same time, the ten-year restriction on participation in the competition for individuals who held positions in NABU is expected to remain in place and to be extended to SAPO employees as well.

These restrictions were introduced because holding such positions or engaging in related activities could negatively impact the impartiality of new judges in their decision-making. In practice, these restrictions were intended to establish a so-called “cooling-off period” for individuals who would work directly with HACC judges, such as NABU detectives. It was also important to prevent the HACC from inheriting the institutional culture of bodies that historically had an extremely low level of public trust in Ukraine, such as customs authorities and the tax police. This approach was appropriate, considering the intention to establish an institution with a “clean slate” to the greatest extent possible.

Removing or easing restrictions on competition eligibility for employees of certain bodies will indeed broaden the pool of potential candidates. At the same time, the draft law does not propose eliminating evaluation stages or granting advantages to specific groups of candidates based on their previous experience. This means that all competition participants will still be required to undergo an assessment to demonstrate their competence and compliance with integrity criteria, including evaluation by the PCIE.

At the same time, it would be advisable to reconsider the proposed restriction for NABU and SAPO employees before the draft law’s second reading in the Verkhovna Rada. Reducing the restriction period to five years would allow some former employees to participate in the competition. This period is sufficient to neutralize any information or connections acquired in these bodies and prevent them from negatively influencing a judge’s work. Any potential or actual conflicts of interest can be addressed through the recusal (challenge) procedure.

The second proposal would also help attract a larger pool of potential candidates to participate in the competition.

The provision restricting the participation of candidates who, within a year, failed to appear, refused to take, or did not pass the qualification exam was intended to establish a “cooling-off period” for those who took the test but did not score enough points. It is assumed that, over the course of a year, such candidates would no longer remember the tasks they completed during the testing or discussed with other participants in the selection process. However, considering that the database of legal test questions with answers is publicly available, new practical tasks will be developed for each competition, and the cognitive ability test database will be updated, this risk will not be relevant for the upcoming HACC competition.

The removal of the requirement to score 75% of the maximum possible points on the Ukrainian statehood test is clearly a continuation of the legislator’s practice of easing requirements for candidates. The threshold score will be set by the HQCJ’s decision.

This type of testing will be conducted in Ukraine for the first time. This means that the task database will still be formed. Establishing a threshold score in the law without a proper understanding of the task database’s complexity may lead to negative consequences, such as the unjustified disqualification of a significant number of candidates or, conversely, an unreasonably low entry barrier.

In this context, the decision to remove such a requirement may be justified. At the same time, as with cognitive ability testing, the HQCJ will need to determine the threshold score and formalize the procedure for setting it.

The changes proposed by the MPs do not address all the problems identified in the HACC competition; however, if adopted, they will help resolve some of these issues. At the same time, the HQCJ must also take into account the lessons learned to ensure a high-quality competition at the organizational level.

The changes proposed by the MPs do not address all the problems identified in the HACC competition; however, if adopted, they will help resolve some of these issues. At the same time, the HQCJ must also take into account the lessons learned to ensure a high-quality competition at the organizational level.

Contributors

Kateryna Ryzhenko, Deputy Executive Director for Legal Affairs, Transparency International Ukraine

Authors of the study:

Pavlo Demchuk, Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine;

Andrii Tkachuk, Junior Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine.

Editor:

Viktoriia Karpinska